Nowadays you can meet female scientists all over the world and it won’t come as a surprise to anyone. Only this spring, on March 19 to be exact, the prestigious Abel Prize for mathematics was awarded to a woman for the first time.

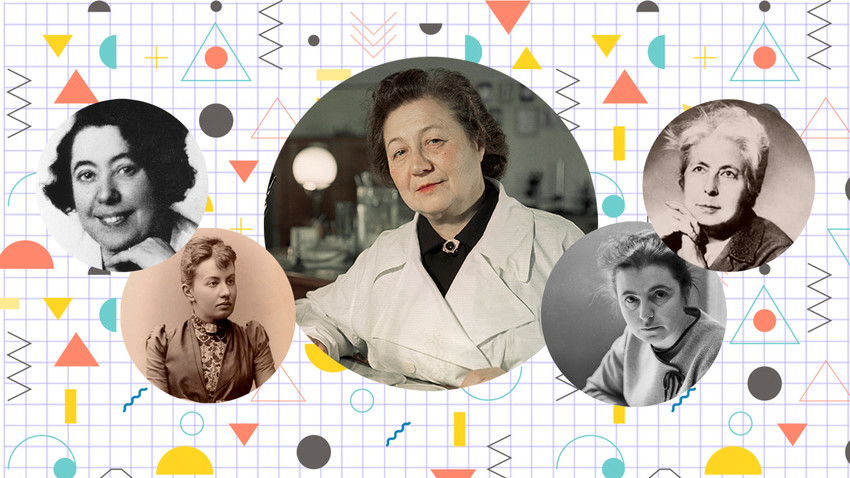

The first higher education courses for women started appearing in Russia about the same time as in Europe, in the 1870s, but the right of women to have an equal education with men was only fully realized in the 1920s. Despite this, the examples of scientists such as Zinaida Yermolyeva, Sofia Kovalevskaya, Lina Stern, Olga Ladyzhenskaya and Fatima Butaeva show that even in the most difficult times, women's aspirations in science found ways through.

One of the founders of Russian microbiology, Zinaida Vissarionovna Yermolyeva (1898-1974) didn't choose her profession by accident. In 1915, she decided to become a doctor after learning that her favorite composer, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, had died of cholera. Zinaida decided to devote her life to fighting the disease and entered Donskoy State University from which she graduated in 1921.

During a 1922 cholera epidemic, Zinaida almost died after she conducted an experiment on herself: Researching ways of contracting the infection she deliberately drank water containing choleroid vibrios. Thanks to her bold and life-threatening experiment, modern standards of water chlorination were created.

In 1939, she was sent to work in Afghanistan where she invented methods for the rapid diagnosis of cholera and an effective drug, not only against

One of the major achievements of the Soviet microbiologist was the development of the first Russian antibiotic,

After her husband's suicide in 1883, Sofia went with her daughter to Berlin. She secured a professorship at Stockholm University, where she read lectures and published work in Swedish. In 1888, the first woman professor wrote a work on ‘The Rotation of a Rigid Body about a Fixed Point’ in which she discovered the third classic way of solving the problem, moving forward the work started by Leonhard Euler and Joseph-Louis Lagrange.

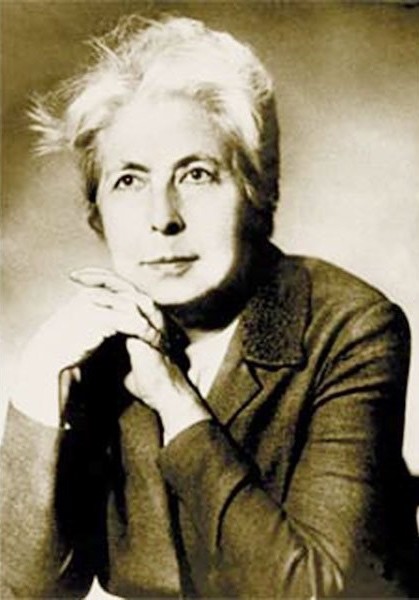

The eldest child in a large Jewish family, Lina Solomonovna Stern (1878-1968) was born in the Courland Province (now Latvia) of the Russian Empire. She was the first woman awarded the title of professor at the University of Geneva, where she had studied, later becoming the first female academician in the USSR, to which she returned in 1925, having been offered the position of head of the Department of Physiology at the Second Moscow State University (since 1930 - the 2nd Moscow Medical Institute).

An incredibly energetic and hard-working woman, from 1925 to 1949 Lina Solomonovna was the head of the Department of Physiology and simultaneously (1929-1948) director of the Institute of Physiology of the People's Commissariat for Education of the RSFSR (later - the USSR Academy of Sciences). In 1932, Stern was elected a member of the German Academy of Natural Sciences and, in 1939, an academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences. The main focus of her research was the study of the chemical and

Under her leadership, an electro-impulse method for halting the ventricular fibrillation of the heart was developed and the first cardiac electrotherapy device created. A method of treating wound shock, which went on to be widely applied in military hospitals during World War II, came out of the work done by Stern. And in 1947, she proposed an effective method for treating tuberculous meningitis by introducing streptomycin into the cerebrospinal fluid directly through the cranium.

Science once saved Stern’s life: in 1949 she was arrested over the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

She eventually managed to enter the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics of Moscow State University (MGU) in 1943, and in 1947 she commenced postgraduate studies at LGU, where she subsequently earned a doctorate in Physical and Mathematical Sciences and became a professor of the Department of Higher Mathematics and Mathematical Physics at LGU’s Faculty of Physics. Known for her austere

Like her father, Olga had wide interests and loved not only the sciences but also

As a result of her research, Fatima became famous as the co-inventor of the first fluorescent lamps, for which she was awarded the Stalin Prize, Second Degree, in 1951. In the same year, Butaeva and her colleagues applied for a patent for a new principle for light amplification, which is today applied in all lasers. The discovery was ahead of its time and the patent was only granted eight years

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox