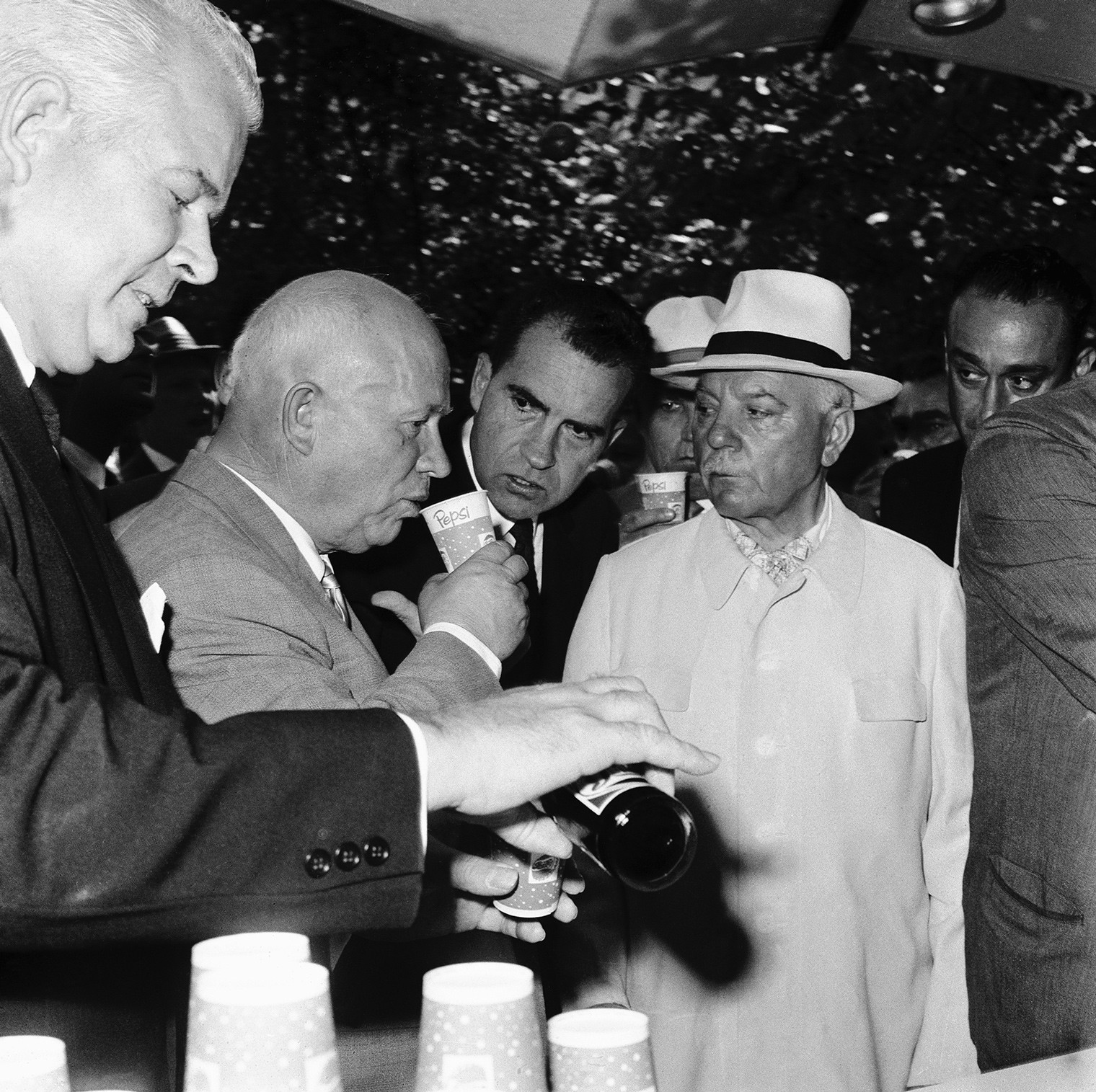

Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the USSR, talking to the U.S. Vice-President Richard Nixon, 1959.

APFor Soviet people, disputes in kitchens were a national pastime: ever since the 1930s, political debates were outlawed save for the Communist Party and publicly expressing any kind of skepticism or criticism of the Secretary-General was risky, to say the least. That’s why Soviet dissidents would spend hours in their kitchens – among a close circle of friends, in low voices, they would discuss things they couldn’t dream of saying anywhere else.

Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the USSR in 1953 – 1964, was by no means a dissident. But he took the kitchen talk to a whole new level in 1959: he managed to argue with Richard Nixon (Dwight Eisenhower’s VP back then) right in an ‘American kitchen’ at the U.S. exhibit in Moscow.

Richard Nixon cuts the ribbon, officially opening the exhibit.

Getty ImagesThat year, both the USSR and the U.S., following the bilateral Cultural Agreement adopted in 1958, organized exhibits showing the industrial achievements of each country and aimed at promoting understanding: one in New York City and one in Moscow.

“[The Soviets focused on] showing their progress in science and technology,” wrote Alexey Fominykh in the article devoted to the exhibit. They brought rockets, satellites (the cosmic race was on), a nuclear power vessel and so on, to New York. But Americans chose another approach.

Soviet observers are being shown what a supermarket looks like.

Getty Images“Unlike their counterparts from the USSR, they made the American everyday life the central theme of the exhibit,” notes Fominykh. Instead of exhibiting their military and space prowess, the United States Information Agency (USIA) and the Department of Commerce, who were in charge of organization, decided to entice the Soviet people with the goods of capitalism: shiny cars, fancy cosmetics and Pepsi-Cola.

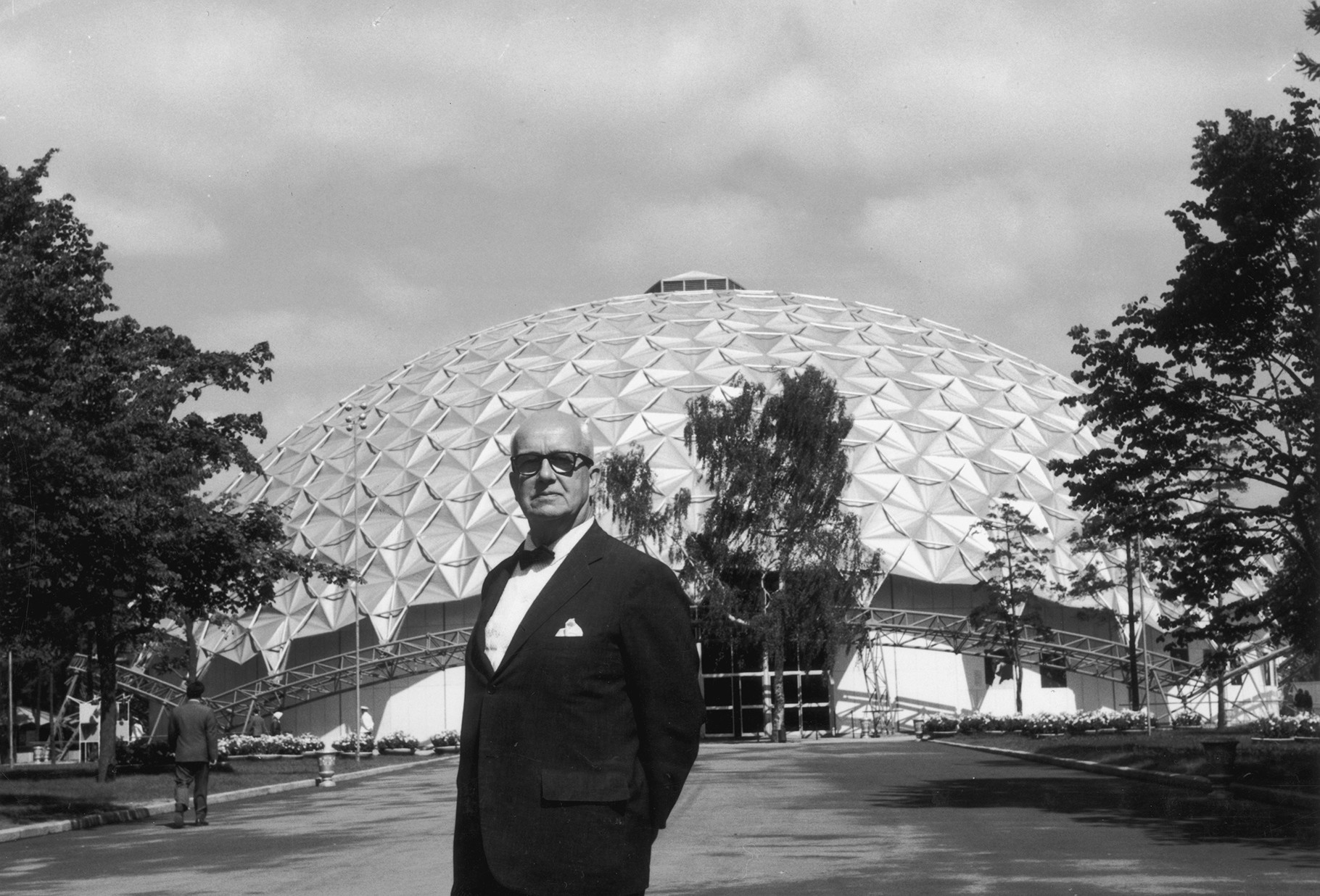

American architect and inventor Richard Buckminster Fuller posing in front of the 'golden dome' that he helped to project - and that became a real eye-catcher in Moscow.

Getty ImagesThe Communist Party bosses did their best to reduce the ideological damage: they forbade Americans to display any anti-Soviet literature or air Soviet-American debates. The exhibit had to be non-political. The American side agreed to all requirements. As it turned out, they needed no political propaganda to amaze the Soviet society.

In seven months, they built several pavilions, including the ‘golden dome’, designed by George Nelson. “That dome made the biggest impression on everyone: you could see it the second you exited Sokolniki Metro Station, it was really eye-catching,” recalls art historian Vladimir Aronov, who used to frequent the exhibition.

Inside the golden dome, there were seven giant screens playing a film about American life and multiple scientific exhibits. Among the most impressive was an IBM RAMAC computer, programmed to answer questions about America. But pavilions demonstrating everyday life of Americans proved to be even more popular.

Soviet people and American cars.

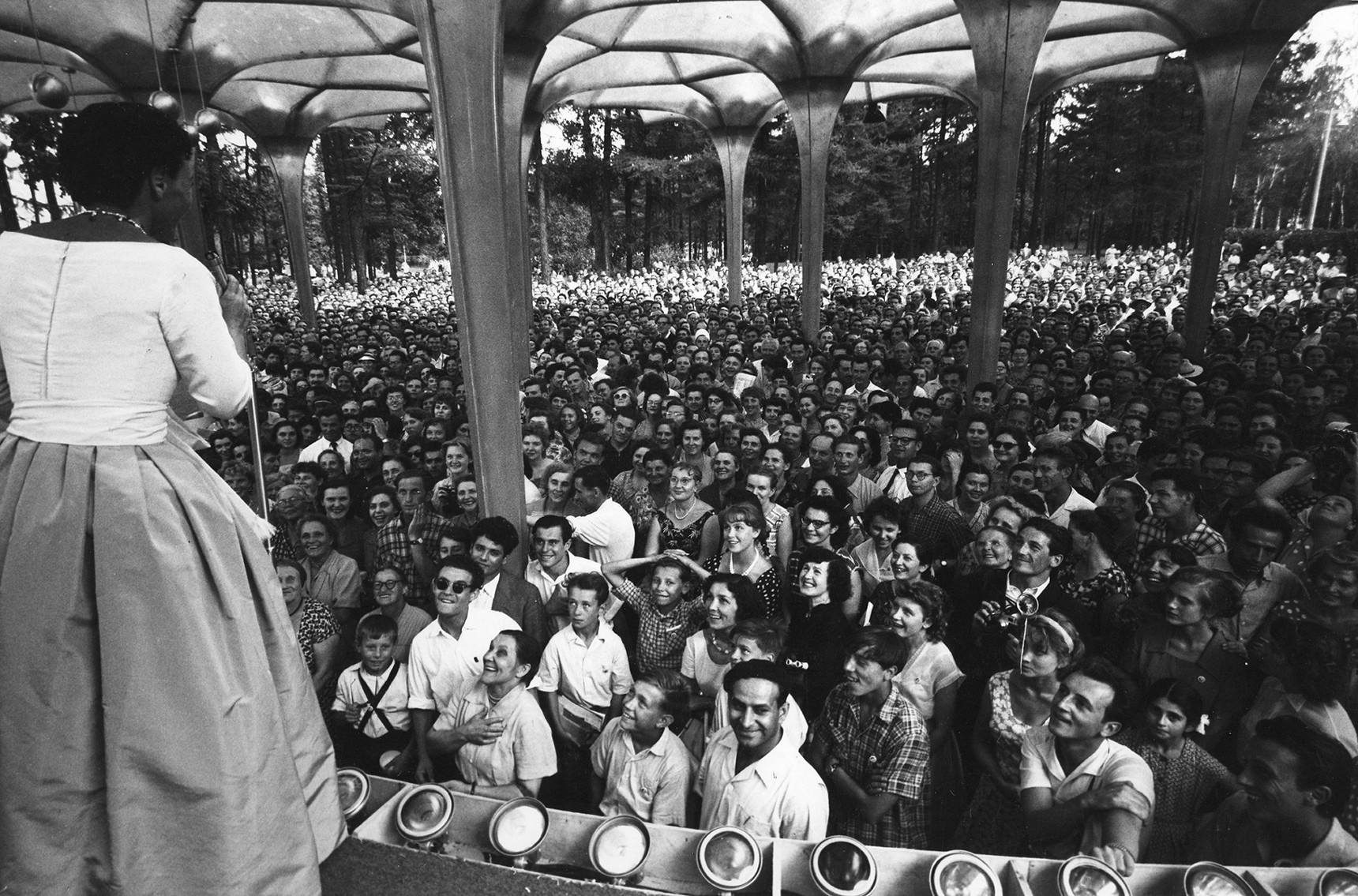

Anatoliy Garanin/Sputnik“The Americans had an idea that design that really changes the world enters our houses not through the front entrance, but through kitchens, bathrooms and garages,” says Vladimir Aronov. So, 768 American brands presented their production, from toys to kitchen sets – and the Soviets loved them. The exhibit lasted for 6 weeks; during that time, 2,7 million people visited it.

America’s automobile industry was especially a hit with the men. “Even half a century later, the exhibit is remembered for the cultural shock, thanks to the Cadillacs, Buicks and Lincolns, with its ‘Detroit baroque’ design,” writes Oldtimer website. For the ladies, cosmetics and make-up pavilions were the catch, along with fashion shows: “Three times a day, models in Russian fur coats were dancing rock-n-roll with young Americans.”

Quite a rare photo - Nikita Khrushchev sipping a Pepsi.

Getty ImagesAs for Pepsi, each visitor could drink as much as they wanted – that was the first time Muscovites massively tasted that capitalist soda. Even Nikita Khrushchev, while visiting the exhibit, had a sip and seemed to be happy.

Nixon (R) and Khrushchev (in the center) discussing the pros and cons of the American and the Soviet ways of life.

IIP Photo Archive/WikipediaThe Soviet leader, famous for his love to argue, found a good competitor at the exhibition – Richard Nixon, who, as the Vice President of the U.S., was hosting the opening on July 25. The two disputed on the advantages and disadvantages of the Soviet and American ways of life while Nixon was touring Khrushchev around the exhibit, including the ‘typical American kitchen’, which later led to the nickname “kitchen debate”.

Khrushchev claimed that, with all due respect, the exhibit was not that impressive and Soviet design was competitive enough. “Your American houses are built to last only 20 years so builders could sell new houses at the end. We build firmly. We build for our children and grandchildren,” he said to Nixon.

A fashion model at the U.S. Exposition in Sokolniki Park answers questions about her clothes and life in the U.S.

Getty ImagesThe VP fought back: “This exhibit was not designed to astound, but to interest. Diversity, the right to choose, the fact that we have 1,000 builders building 1,000 different houses is the most important thing. We don’t have one decision made at the top by one government official.”

Khrushchev, admitting the high quality of American furniture, cars and everyday life, replied that he was sure in 7 years, the USSR would “be on the level of America and we’ll go further, as we pass you by, we’ll wave ‘hi’ to you!”

While the debate was quite heated, especially with Khrushchev’s knack for the extravagant – for instance, he used the rare expression, “We don’t beat flies with our nostrils!” meaning, “We don’t waste our time!” (which surely must have almost given the translator a heart attack) – the two men smiled all the time and were quite friendly to each other.

It was just three years before the Cuban missile crisis – but back during the exhibition, no one thought of any war. “When we were leaving the exhibit we felt that if the world unites it would be a better place for us all,” recalled Aronov. Unfortunately, it never happened like that and who knows if it ever will.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox