The right to life hasn’t always been a basic human right. In medieval times, when people were divided into strata, judging by their ancestry and wealth, some human lives were indispensable, and others were ‘cheaper’ than the others, and therefore expendable. This was also true for Russia. Read on to see how the notion of the cost of human life transformed through the centuries.

'Justice under the Rus' Law' by Ivan Bilibin

Private collectionRusskaya Pravda (Rus’ Law), the oldest known law code of Kievan Rus’ defined certain fines for killing certain types of people. The law code applied to Russia’s ruling class, peasants and townsfolk until the 15th century.

Fines were counted in grivnas. A grivna (which was equal to roughly 150 to 200 grams of silver) was a unit of weight and currency used in Kievan Rus’. A grivna was considered quite expensive. It could buy an entire village of 5-6 houses, or a fully trained and healthy battle horse. Half a grivna was a year’s pay for a slave’s work.

'At the court of a Russian prince' by Appolinary Vasnetsov

State Historical MuseumThe fine for killing a free man was 40 grivnas, a free woman – 20 grivnas. If the man served the knyaz’ (as an official, soldier or house servant), the fine would double to 80 or 40 grivnas, respectively. The money was paid to the local administration – i.e., the knyaz’. But it wasn’t possible to pay the fine in advance, of course.

Ancient Russian grivnas

Public domainFor the killing of dependent people – kholops (a kind of serf), the fine was lower: “For a village supervisor, or the field work supervisor, 12 grivnas. And for a serf, 5 grivnas… For a serf woman, 6 grivnas… For a teacher, 12 grivnas, same for a nanny, whether they be serfs or women,” the Rus Law stated.

Needless to say, common folk couldn’t pay off the enormous fine, so the village community usually paid for its members in such case.

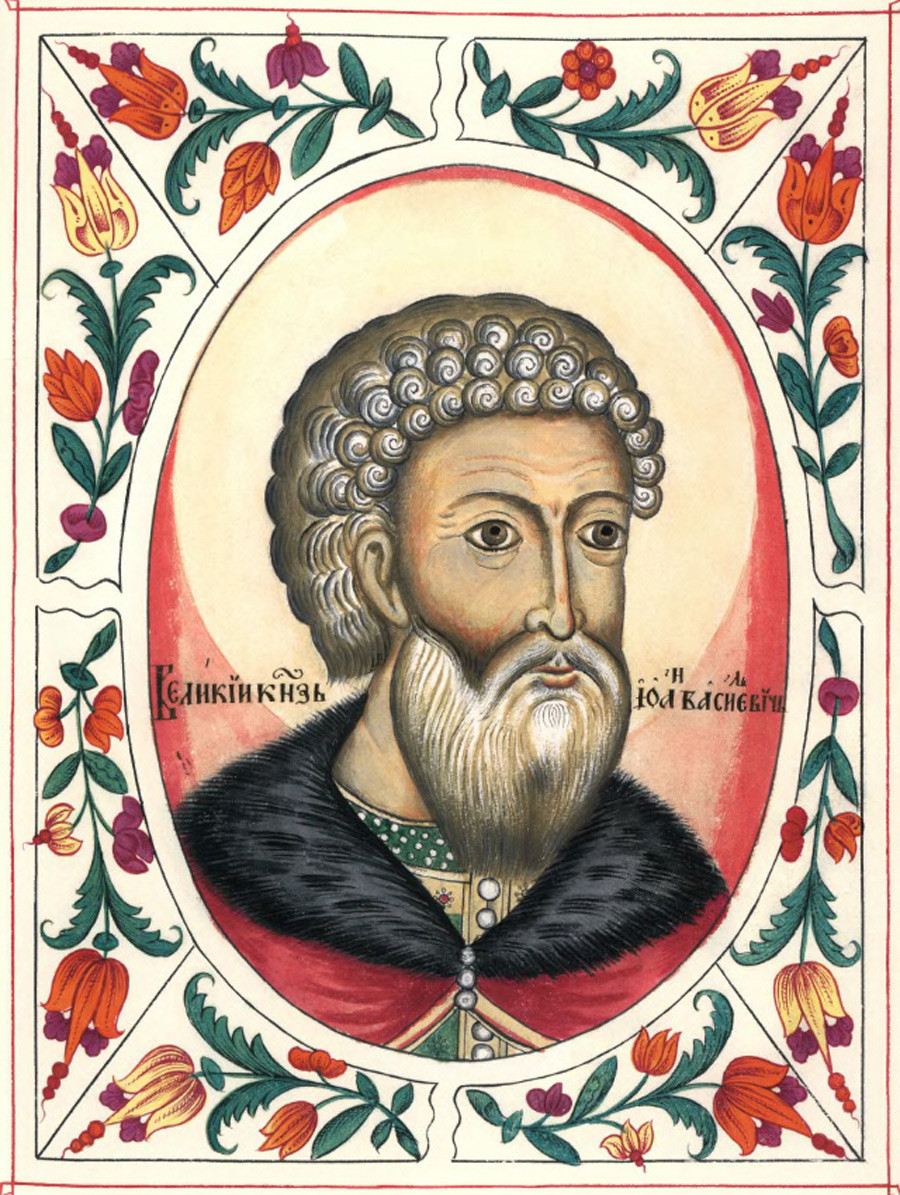

Portrait of Ivan the Great (1440-1505)

Public domainIn 1497, Ivan the Great of Russia introduced a new Code of Law. It stated that the killing of a man should be punished with a death penalty – if the murderer is a known criminal (i.e. that he commits murder for a second time) or if a murderer is a serf that kills his master.

According to the 1497 Code of Law, a “simple” murder of a free man would cost 4 roubles. This was, also, a huge sum. We know that in the year 1534, 0.03 of a ruble bought you a log house (Rus: izba).

'Zemsky Sobor' by Sergey Ivanov

I. Knebel publishing houseIn 1550, Ivan the Terrible introduced a new Code of Law. From then on, murder was subject to a formal trial, and fines were no longer accepted for killing a man. Intentional murders were punished with death, unintentional – with public whipping or jail time (however, the notion of self-defense was also introduced). A fine remained only in case of ‘dishonoring’ somebody with words or actions.

Sobornoye Ulozhenie (1649) legalized serfdom in Russia – now, serf peasants were the property of landlords, who could buy and sell them, so a price was put on human life again.

'Serf auction in the 18th century' by K. Lebedev

Global Look PressIn the 18th century, a full serf trade developed in Russia. Purchases of serfs were registered in special books because every deal had to be taxed. Prices for serfs ranged according to their age, gender, abilities, and greatly varied.

During Catherine the Great’s reign, the price for a working adult serf had risen from 30 to 100 rubles (a ruble could buy you a bucket of vodka, 16 kilos of bread, or a ride from Moscow to Saint Petersburg). In 1782, a landlord typically sold his serfs for the following: a 28-year-old man for 40 rubles, a 25-year old woman for 10 rubles, an 11-year old boy for 11 rubles. Prices were lower if serfs were sold wholesale – for example, the whole village.

In the 19th century, prices skyrocketed for professional serfs. A shoemaker serf cost 500 rubles (equal to the salary of a high-ranking official), an experienced cook or a barber could cost up to 1000 rubles. The highest prices were for musicians, actors, and actresses, who could cost a fortune – up to 5000 rubles or even more.

In the USSR no slave trade or murder fines ever existed. In contemporary Russia, we can assess the “price” of human life by the reparations the state pays the families of citizens who perished in catastrophes, natural disasters and terrorist attacks.

Nowadays, tragic death or injury of civilians that was partly the state’s fault is usually compensated from the budget of the region, and the amount of money varies greatly from region to region, a report says. In a train crash in 2013, five children were injured, and the Russian railways’ insurance operator promised to pay them 300 thousand rubles ($4,800); meanwhile, three children injured in the Moscow Zoo were paid 500 thousand ($8,000). Families of those who perished in the Krymsk (Krasnodar region) flood of 2012 received about 2 million rubles ($32,000).

Since 2013, 2.25 million rubles ($36,000) is the fixed amount of insurance payout for death in a plane, bus, or train crash. Mass catastrophes, in turn, have a massive negative impact over society, and usually the federal government also adds to the regional and insurance compensations. Not to forget that not all insurance companies operate honestly. Unfortunately, there are many people who failed to receive their compensations after the untimely death of their relatives and/or loved ones.

In 2018, a fire in the ‘Zimnyaya Vishnya’ mall in Kemerovo killed 60 people, including 37 children. 450 people, including 84 relatives of the deceased, were recognized as victims and injured parties; for each of the deceased, their families received over 5 million rubles ($80,000) of compensation. The injured and distressed persons received from 200 thousand ($3,200) to 400 thousand rubles ($6,400).

After the SSJ100 plane catastrophe at Sheremetyevo airport on May 5, 2019, where 41 people died in a plane fire, relatives were paid 2 million ($32,000) from the Moscow region and various sums from other regions, insurance companies and other parties. It is important to note that recently, charity, crowdfunding and public donations for the victims of catastrophes also raise considerable funds.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox