De-facto the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact meant the division of Poland between the USSR and Nazi Germany.

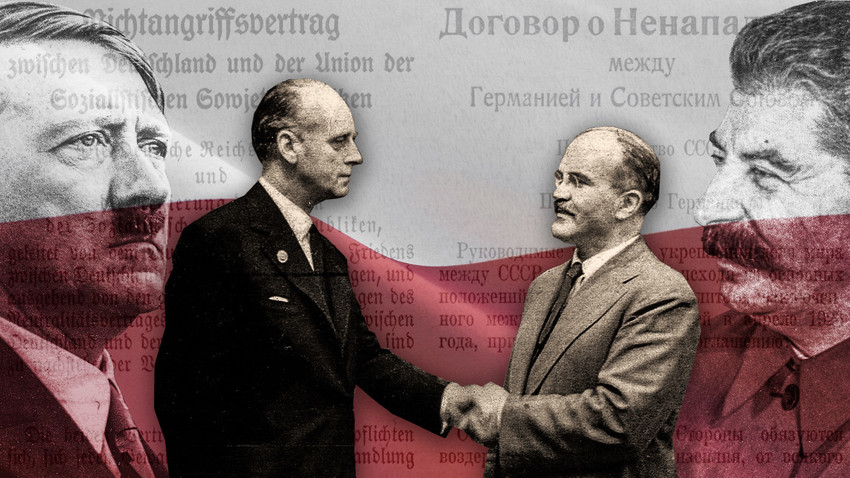

Georgy Petrusov/Sputnik; Global Look Press; PixabayJoachim von Ribbentrop, the Nazi Foreign Minister arrived in Moscow on August 23, 1939, shocking the international community. Just months before, imagining a minister of the Third Reich coming to Moscow to talk peace with Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov (USSR’s Foreign Minister) was impossible.

Communist Russia and Nazi Germany seemed natural born enemies. Hitler was constantly speaking about the Reich gaining the Lebensraum (“living space”) in the East, which meant seizing Soviet territories. The USSR had constantly criticized Nazi Germany from the moment Hitler came to power in 1933 and positioned itself as the major anti-Nazi power.

As American ambassador in Moscow, Charles Bohlen would recall, even the swastika flag the Soviets hanged in the airport to welcome Ribbentrop had previously been used only in anti-Nazi movies shot in Moscow. However, now Moscow and Berlin were negotiating peace. And a little bit more.

Molotov signing the German-Soviet Frontier Treaty, a supplementary protocol to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Stalin can be noticed behind his back.

Public domainHitler was in a hurry when sending his Foreign Minister to Moscow. In recent years his Reich has been expanding: the Anschluss of Austria (March 1938), the annexation of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland (September 1938), and occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia (March 1939). Now it was Poland’s turn – and Hitler badly needed guarantees that the USSR would not declare war on Germany.

It was urgent – the assault on Poland was scheduled for August 25, the army was ready, all the orders were given. Hitler had to act quickly. “So he decided to go all-in,” as History of International Relations (edited by Anatoly Torkunov, the rector of Moscow's State Institute of International Relations) states. “On August 21, 1939, he addressed Stalin, asking him to meet Ribbentrop no later than August 23.”

Stalin agreed. Things went smoothly: it took just hours to reach an agreement. That night, Ribbentrop and Molotov signed the treaty – and a secret protocol to it.

Adolf Hitler among the Wehrmacht soldiers during Germany's Polish campaign of 1939.

Narodowe Archiwum CyfroweThe pact itself was a pretty standard non-aggression treaty. The USSR and Germany stated they would refrain from any acts of violence and any alliances that were unfriendly to the other party and stay neutral if the other party was attacked by a third state.

On June 22, 1941, 22 months after the signing, Germany would break the pact, attacking the USSR with all its power. For Hitler, international agreements were just pieces of paper – and Stalin shared that attitude. “Signing the pact, both Hitler and Stalin were sure that war [between the USSR and Germany] was inevitable,” Torkunov writes. The most important thing about the pact was a secret protocol that enabled Stalin and Hitler to agree upon the future Soviet-German border.

The division of Poland.

Lonio17 (CC BY-SA 4.0)“In the event of the territorial-political reorganization of the districts making up the Polish Republic, the border of the spheres of interest of Germany and the USSR will run approximately along the Pisa, Narew, Vistula, and San rivers,” said the protocol. “The question of whether it is in the mutual interest to preserve the independent Polish State, can be ascertained conclusively only in the course of future political development.”

The “future political development” erased Poland from the map. On September 1, 1939, 1.5 million Wehrmacht soldiers marched into Poland from the west, annihilated the Polish army in two weeks and captured Warsaw. On September 17, the Red Army also entered Poland, from the east, meeting basically no resistance and occupying all territories within its “sphere of influence.” Later, in 1940, Moscow forced three Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) to join the USSR, thus completing its territorial expansion.

Molotov and Ribbentrop shaking hands after signing the pact and protocols.

Public domainThough unpublished, the protocol was barely secret – German diplomats leaked information to their colleagues so soon the entire world at least suspected what Moscow and Berlin had agreed on. “There is a growing belief that… Germany and Russia have agreed on the partition of Poland, and that the Baltic States are to be a Russian sphere of influence,” wroteThe Guardian just days after the treaty was signed. The USSR, however, denied the existence of the treaty until 1989.

Today, Russian leaders’ position towards the pact is moderate: nothing to be proud of but not a cause of shame. “The Soviet Union… made repeated attempts to create an anti-fascist bloc in Europe. All of these attempts failed,” Vladimir Putin said in 2015. "And when the Soviet Union realized that it was being left one-on-one with Hitler's Germany, it took steps to avoid a direct confrontation.”

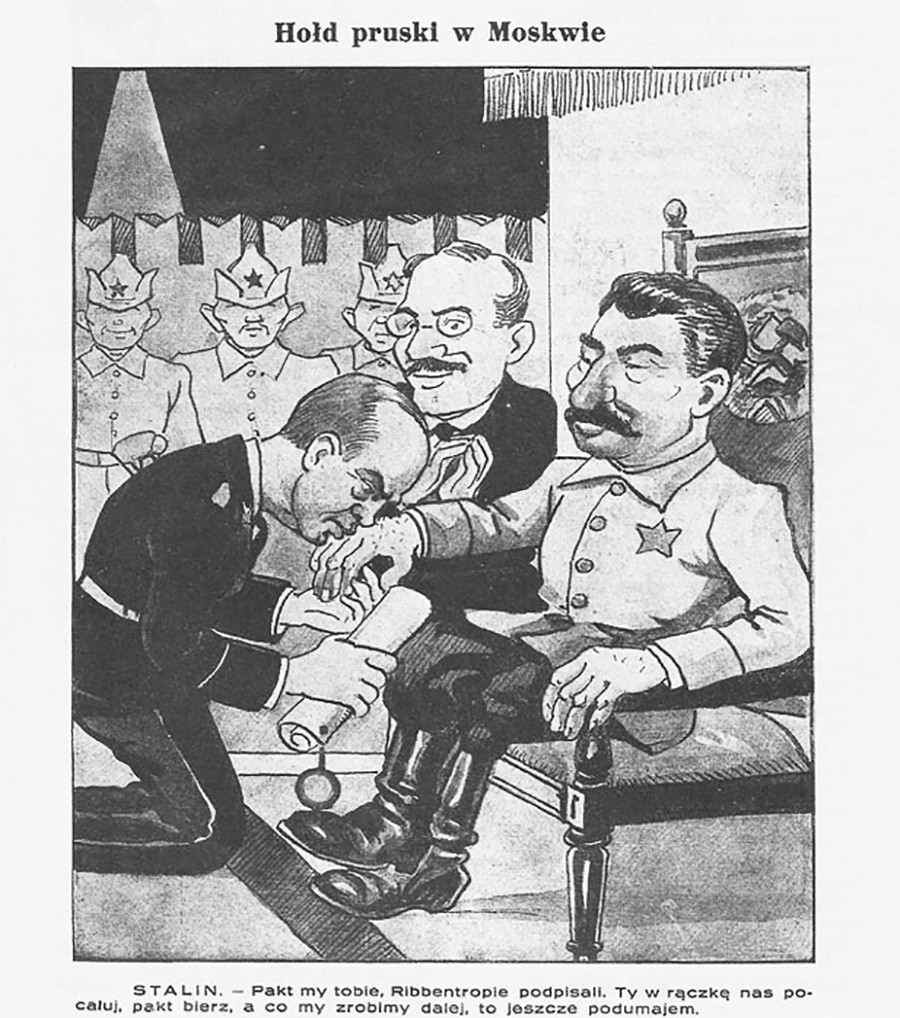

Polish satire of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. Cartoon printed in September 1939.

Public domainUnlike Putin, Western media and scholars traditionally criticize the pact as vicious and immoral. It’s hard to define who is closer to the truth. “Of course, the pact was a cynical deal with the devil for the sake of our country’s interests,” historian Alexey Isaev admits. But it did help the USSR to prepare for war. “Our strategic situation got better in 1939. The 180 miles from the old border to the new one gave the USSR palpable benefits in terms of time and distance,” Isaev says.

The case is that the USSR wasn’t the first European power to make such a deal with the devil. Two leading democratic states of Europe, the United Kingdom and France, appeased Hitler over and over again. They let him remilitarize Germany and enlarge its army and annex Austria – and directly pressed their ally Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland to Hitler during the Munich Conference of September 1938. Unlike Stalin, Britain’s Neville Chamberlain and France’s Édouard Daladier won nothing from their deals with Hitler – just provoked the aggressor to conquer more and more.

“The appeasement policy was wrong and counter-productive because it was impossible to fulfill the Nazis’ unlimited appetites,” states Torkunov. “Moscow’s actions, as cynical as those of London and Paris, had more serious motivation.” In other words, Stalin, seizing territories and gaining time, acted immorally but rationally – Chamberlain and Daladier, trying to appease Hitler, acted as immorally but also stupidly.

You know how it all ended. Hitler couldn’t be stopped by any kind of deals – it took WWII with its 60 million victims to stop him and prevent the dystopian future that would have emerged had he won. As for the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, it remains one of many shameful pages of the history of the pre-war period.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox