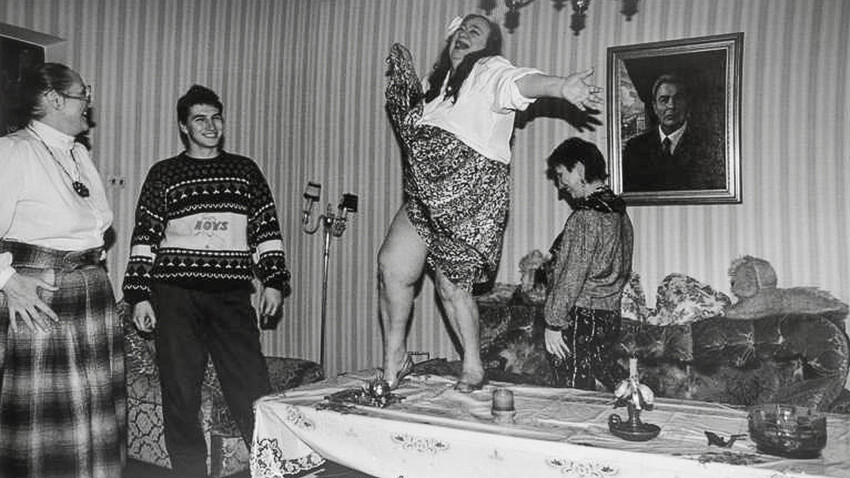

Galina Brezhneva

Yuri Rybchinsky / MAMM / MDF / russiainphoto.ruStalin’s right-hand man and the head of the NKVD, Lavrenty Beria, had only one son. Sergo carved himself a brilliant career as a military engineer.

Sergo Beria

Archive photoAt the very beginning of WW2, the then 20-year-old young man took an accelerated three-month course at the NKVD radio engineering laboratory, and joined the army with the rank of lieutenant technician. In 1941 he was sent on a secret special op to Iran, in 1942 he served in the North Caucasus Group of Forces, and later, on a special assignment, he attended the Tehran and Yalta conferences among the heads of the anti-Hitler coalition. After the war, Sergo graduated from the Leningrad Military Academy of Communications. While working on his diploma, he designed the first Soviet air-to-sea KS-1 Kometa-class cruise missile, and became one of the country’s top military engineers. His master’s and doctoral dissertations were based on his projects, for which he also received the Order of Lenin and the Stalin Prize.

But everything changed dramatically after the arrest and execution of his father in 1953. Sergo was placed in solitary confinement for a year, and deprived of all ranks, awards, and academic degrees. A commission found him guilty of plagiarism, his dissertations were deemed to be reworkings of studies by other researchers and engineers. In 1954, together with his mother, he was sent into “administrative exile” in the Urals, where he was nevertheless given a three-room apartment and the right to work on his rocket designs. Son and mother also changed their surname to Gegechkori, convinced that “with the surname Beria people would tear [us] apart.”

Sergo Beria

Sputnik“Gegechkori was his mother’s maiden name. He always used it when introducing himself. Not once did he mention that his father was Lavrenty Beria,” said his colleague Rel Matafonov in the 1950s. Sergo began his career from scratch, as an ordinary engineer, rising to prominence once again over the years. In 1964 he requested a transfer to Kiev, Ukraine, where he continued to climb the career ladder. From 1990 to 1999, Sergo worked as a chief designer at the Kiev Research Institute. Later in life he ceased hiding the fact that he was the son of Beria, and even wrote his memoirs in which he desperately tried to rehabilitate his father, whom he loved dearly. He firmly believed that Beria had been scapegoated for the crimes of the party elite, and that all his father’s actions had been in the interests of the state.

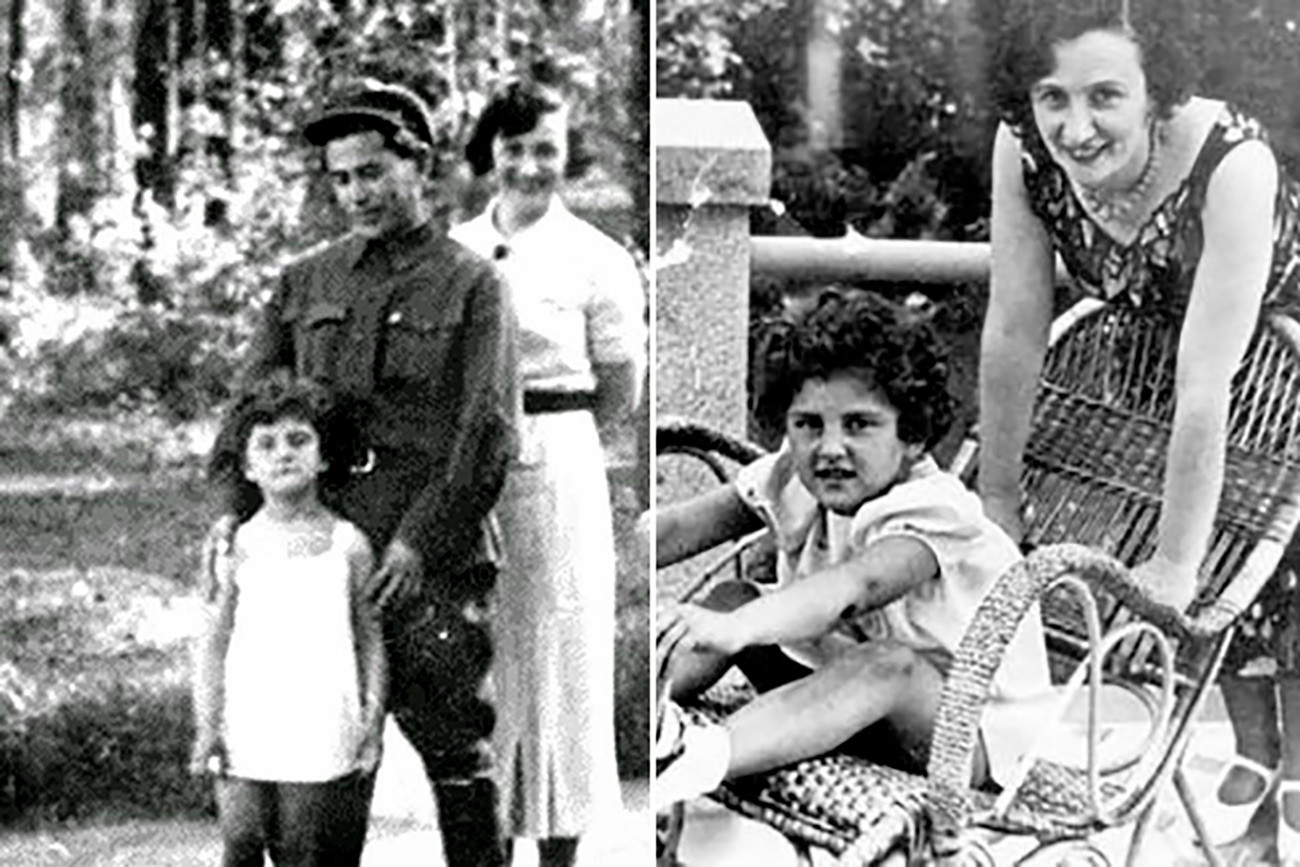

Leonid Khrushchev

Archive photoThe man who debunked Stalin’s personality cult had six children, but it was the eldest son, Leonid, who shone the brightest.

The son of the future secretary general of the Soviet Union started his working life in a factory. But in 1939, when the Soviet-Finnish War broke out, he voluntarily enlisted in the Red Army and requested a transfer to the front as a bomber pilot. During this brief war, he flew 30 sorties.

A year later, in June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union in what became known as the Great Patriotic War. Leonid again went to the front, but suffered a crash early on, in July, and was seriously wounded. A year later, his leg still injured, he was again dispatched to the front, this time as a fighter pilot. According to the memoirs of his sister Rada, her crippled brother was sent back to the front as a punishment for having accidentally, and allegedly, shot a sailor in 1942 while drunk at a party (Leonid’s granddaughter, Nina Khrushcheva, believes that the incident was made up and that there is no evidence for it). In any event, Khrushchev’s son continued flying; in 1943 he failed to return from a sortie and was declared missing in action.

According to the official version of events, Leonid was shot down while covering a friend’s plane from a German Focke-Wulf. But there is also a conspiracy theory, conceived, as is now believed, by Stalinists to discredit Nikita Khrushchev, but very popular at the time.

Read more: In Stalin’s shadow: How did the lives of his family turn out?

It states that Leonid in fact went over to the German side, was kidnapped at Stalin’s request, and shot, with the case subsequently hushed up. The story has never been confirmed, although its “target” was not random:

“Leonid grew up headstrong. That, I think, caused a conflict with his father, because the latter wanted to make him a communist, but he had no intention of becoming one,” says Nina, the great-granddaughter of Nikita Khrushchev. In her words, Leonid behaved like a Moscow dandy, thought himself a cut above the rest, and was hyperactive. Today, he would be considered an “adrenaline junkie,” she says.

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev with Galina Brezhneva

Vladimir Musaelyan/TASSIn her youth, Brezhnev’s daughter dreamed of becoming an actress, but her father sent her to study philology at the university. But that did not “cure” her artistic craving, and Galina found another outlet for her expressive nature.

In 1951, she fell in love with touring circus performer Evgeny Milayev (he was 41, only four years younger than Leonid Brezhnev himself; Galina was 22). Having dropped out of the university, she got a job as a costumier in the same circus, and together they eloped. Although the union produced a daughter, their marriage broke down when Milayev had an affair with a fellow female artiste. Her second marriage was to the son of the famous illusionist Emil Kio, 18-year-old Igor Kio. But after just ten days the couple divorced at the insistence of Galina’s influential father.

When Brezhnev took over the reins of power, his daughter became a magnet for bohemian high society. She eventually found herself a “suitable match” in the shape of Internal Service Lieutenant-Colonel Yuri Churbanov, but spent all her time at soirees, where she became addicted to alcohol.

Galina’s life turned into a nightmare after her father’s death in 1982. High society turned its back on her, her husband was arrested, and anti-corruption proceedings were brought against the Brezhnev family. Her alcoholism became public knowledge. In the end, Galina’s own daughter put her in a psychiatric clinic, where she died of a stroke.

Natalia Khayutina (Yezhova)

Archive photoIn the Stalinist purges of 1937-1938, almost 700,000 people were sentenced to death (according to archival documents), and all in the name of the then head of the NKVD, Nikolai Yezhov. The “bloody dwarf” (he was only 1.50 m tall) had no children of his own, but did adopt a daughter, Natalia.

There are several accounts of how she came into being, including that she was the illegitimate child of Yezhov’s last wife, or that she was the illegitimate daughter of Yezhov himself, or the daughter of a family of Soviet diplomats executed by said Yezhov’s NKVD. Whatever the truth, the girl was adopted at 11 months, and became Yezhov’s main diversion. “He was a terrific father. I remember how he made two-bladed skates for me with his own hands, and taught me to play tennis and gorodki [skittles]. He spent a lot of time with me,” Natalia recalled.

When, in 1938, Yezhov was arrested, he pleaded: “Don’t touch my girl!” Her adoptive mother had already died by suicide, and so Natalia was sent to a special orphanage for “enemies of the people” in a guarded rail car. Even during the journey she was told to forget her previous name, but Natalia adored her father and took any opportunity to talk about who she was. But the stress eventually became too much to bear, and she decided to hang herself. However, the rope did not withstand it. “My whole body was grazed, my dress torn, and this rope was hanging around my neck,” she said.

Later, Khayutina voluntarily moved to a village near Magadan (8,000 km east of Moscow), where her father had exiled many of his victims – in order to be closer to them. In 1999 she took legal action to rehabilitate her father, but the court threw the case out. There in Magadan, she composed poems and songs, rarely leaving the house:

Every knock on the door made her shudder: “I still think one day they’ll knock on the door and take revenge on me for who my father was.” She passed away in 2016.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox