“Bearwalking” – traveling with trained bears who performed tricks – was hugely popular in Tsarist Russia. But in 1867, the Committee of Ministers of the Russian Empire issued a law that put an end to bearwalking. The reasons, the law said, were as follows: 1) cruelty to animals; 2) encouragement of vagrancy and lewd behaviour in bear trainers. After bearwalking became an offense, the practice slowly deteriorated.

In the 17th century, Russian tsars were rather pious – at least publicly. Tsar Alexis of Russia (1629 – 1676) loved foreign board games like chess, checkers, and dice, but banned them for his people. According to the Sobornoye Ulozheniye (Council Code) of 1649, “cards and dice” were declared a criminal offense, on par with theft. It could lead to corporal punishment, mutilation or human branding.

Killing and eating cows was forbidden in Russia because food was scarce and it was considered madness to kill cows that could produce milk – or, even better, more cows. Up until the 19th century, meat would only appear on a Russian peasant’s table on big celebrations, and it was usually meat from older cows.

Killing a calf was considered a devilish deed. Jacques Margeret, a French mercenary in Russia, wrote in 1606: “Bulls and cows multiply remarkably, because Russians don’t eat veal, for this contradicts their religion.” Swedish traveler Peter Petreius wrote around the same time that “for Muscovites, eating veal is even worse than eating human meat” and German traveler Jacob Reutenfels wrote that Ivan the Terrible had once ordered three non-Russian workers to be burned alive, because they killed and ate a calf.

Peter the Great thought that to make it easier for foreigners to do business with Russians, the local folk must stop looking so alien with their beards and weird-looking clothes!

In 1705, Peter issued a law that said: everybody must shave their beards, except peasant serfs. And those who wanted to keep their beard, since 1715, were to pay a really enormous fee – from 50 rubles a year (in those days, 5 rubles could buy you 100 kilograms of salt; 120 rubles was a year’s salary of a junior naval officer). Violators of the law faced hard labor.

The beard tax was revoked only in 1772, because by then, the fashion had changed and Russian merchants and citizens had by and large stopped wearing beards. Beards were for peasants, priests, and merchants.

Paul I of Russia, who ascended the throne after his mother, Catherine II, was concerned that after the French Revolution, upheavals against the state could also start in Russia. Paul was a personal friend of Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette, so he was fear-stricken when he learned of their execution.

Paul banned the following: French-style rounded hats, ‘toupees’ (wigs), whiskers (long moustaches), waistcoats, thick neckties; he even banned words some words!

Instead of the revolutionary-sounding “гражданин” (“grazh-da-nin”, eng. “citizen”), the word “обыватель” (“o-by-va-tel’”, eng. “resident”) was to be used. In the place of “отечество” (“o-te-ches-tvo”, eng. “fatherland”), the word “государство” (“go-su-dar-stvo”, eng. “state”) was to be spoken and written.

After Paul’s assassination, all these bans were lifted.

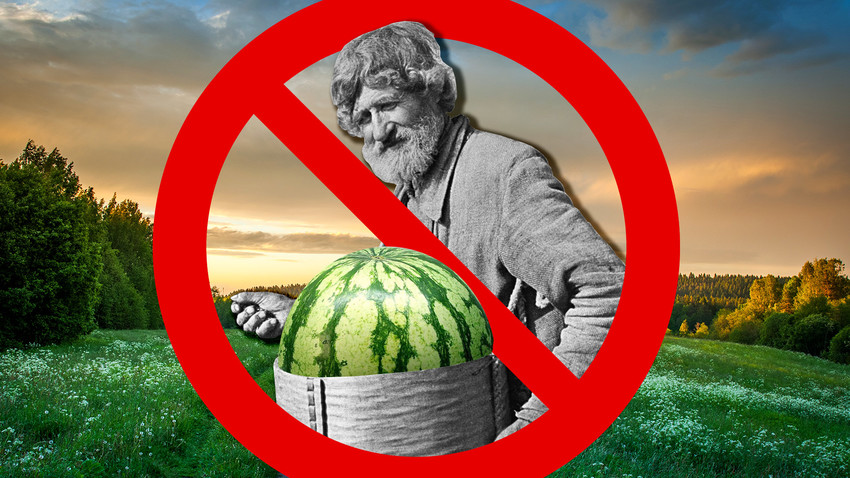

On a certain day of the year, Russian Orthodox believers refrained from eating ball-shaped fruits, and that day was September 11, considered a holy day – the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. Much like on Shabbat in Judaism, work on this day was disapproved of. But what was strange was nobody would eat any round or ball-shaped fruits (like watermelons or apples) or vegetables – because they apparently resembled St. John’s head, in a way!

Also, using knives, swords, sickles, and other cutting equipment was forbidden – on this day, bread was to be broken with hands, not cut.

Tobacco reached Moscow in the 16th century via English merchants. Russians quickly came to love it – they all began chewing and smoking tobacco leaves. But in 1634, Moscow burned down – as the official investigation stated, due to an ember that fell from somebody’s pipe. Since then, tobacco was banned.

Orthodox priests also believed smoking was ungodly, because smoke was generally associated with evil spirits. Smoking could even be punished by exile to Siberia, having one’s nostrils torn open or having one’s lips cut off. Only under Peter the Great, who was an avid smoker, did Russians start puffing on their pipes again.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox