The Moscow University

The Moscow University ChronicleGrigory Potemkin was the son of a retired major from the Smolensk province, who died when the future prince was seven years old. Potemkin was raised by his mother, who sent him to a gymnasium school affiliated with the Moscow University. Having enrolled at the university, he was awarded a medal for achievements in sciences a year later, and joined the university's top dozen best students two years on. Although he did not finish university, Potemkin was noticed at the court and joined the Horse Guards regiment.

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (1739-1791)

Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder“Being tall, he was of a proportionate build, had strong muscles and a high chest. An aquiline nose, a high brow, beautifully arched eyebrows, nice blue eyes, a beautiful complexion with a delicate blush, soft and curly blond hair, even and dazzlingly white teeth,” this is how his biographer, historian Vasily Ogarkov, described Potemkin in his prime. Potemkin was not just a good-looking man: he had a real strength and never feared any difficulties. He used to say: “I am aware of difficulties, but I love working with people who overcome them.”

“He is very brave - he stops under gunfire and calmly gives orders… While awaiting danger, he gets very preoccupied, but once in danger, he becomes merry, and when surrounded with pleasures, he becomes bored... With generals he discusses theology, and with bishops, he talks about war,” Austrian diplomat Count de Ligne wrote about Potemkin.

It goes without saying that Potemkin was extremely popular with women - and was in love with the most powerful of them, Empress Catherine the Great.

Catherine the Great by Dmitry Levitskiy

Dmitry Levitskiy; Tretyakov GalleryAmong Catherine II's favorites, Grigory Potemkin was the closest to her and the one she herself respected the most. It was rumored that they were married in secret. Under Russian tradition, an empress could not marry a man who was so much beneath her socially: she was an empress, while he was a low-ranking nobleman. And even though by the mid-1770s, Potemkin was already an adjutant general and owned huge estates, he earned them, rather than gaining them through inheritance. Furthermore, even had he belonged to the highest ranks of nobility, still he had no royal blood in him. Which meant that the empress could not marry him officially. Yet, for a long time, they lived in the Winter Palace as man and wife. Potemkin’s private chambers were directly above the empress’s bedroom. He alone could enter the empress's chambers at any time and uninvited. In letters, she addressed him as “my dear husband”, and called herself a wife and a spouse.

Prince Potemkin as portrayed by Jason Clarke in HBO's 'Catherine the Great' (2019)

HBO, 2019“The Empire's primary nail biter” – this was how, somewhat caustically, Catherine referred to Grigory Potemkin. Indeed, when deep in thought, he tended to bite his nails, and could not shake this habit, even when he became the second most important person in the country. He loved simple peasant food — pies, porridge, raw vegetables — and always kept it in his chambers. In private letters and when talking to his subordinates, he swore a lot. However, when it mattered for his career, Potemkin was impeccably dressed and exquisitely polite.

Jason Clarke as Grigoriy Potemkin and Helen Mirren as Catherine the Great in HBO's 'Catherine the Great' (2019)

HBO, 2019In 1774, Potemkin was appointed governor of the newly established Novorossiysk province. He was no longer as close to Catherine as he used to be, and he felt the separation acutely. Yet, it was he who, in 1775, introduced Catherine to his subordinate, Peter Zavadovsky, who became her secretary and favorite. Potemkin continued to correspond with Catherine regarding affairs of the state and remained her main adviser. “You have no equals,” the empress wrote to him. Potemkin had enough important matters to occupy him: he ran Novorossiya and was in charge of conquering Crimea. In addition, in 1775, he started to reform the army.

Russian military uniform before and after the Potemkin's reform

Public domainPotemkin was a true military man and knew how important it is for soldiers to feel comfortable. Prior to the reform, they had to wear braided wigs, which needed to be curled on a steel bar. Potemkin wrote: “Curling, powdering, weaving braids, is this a soldier’s business? They do not have valets!” He lifted the requirement to wear wigs and braids from soldiers, although officers continued to wear them.

Potemkin also ordered a change in army uniform: instead of double woolen coats and tight-fitting belts (that uniform looked beautiful, but was terribly uncomfortable), he introduced simple trousers, jackets and boots. Elaborate hats were replaced by practical helmets. But the main thrust of his reform was respect for the soldier: Potemkin banned using soldiers as free labor, repeatedly spoke of the need for a humane attitude to soldiers and took care of their health, because he knew that in a war more soldiers were killed by filth and disease than by bullets and shells.

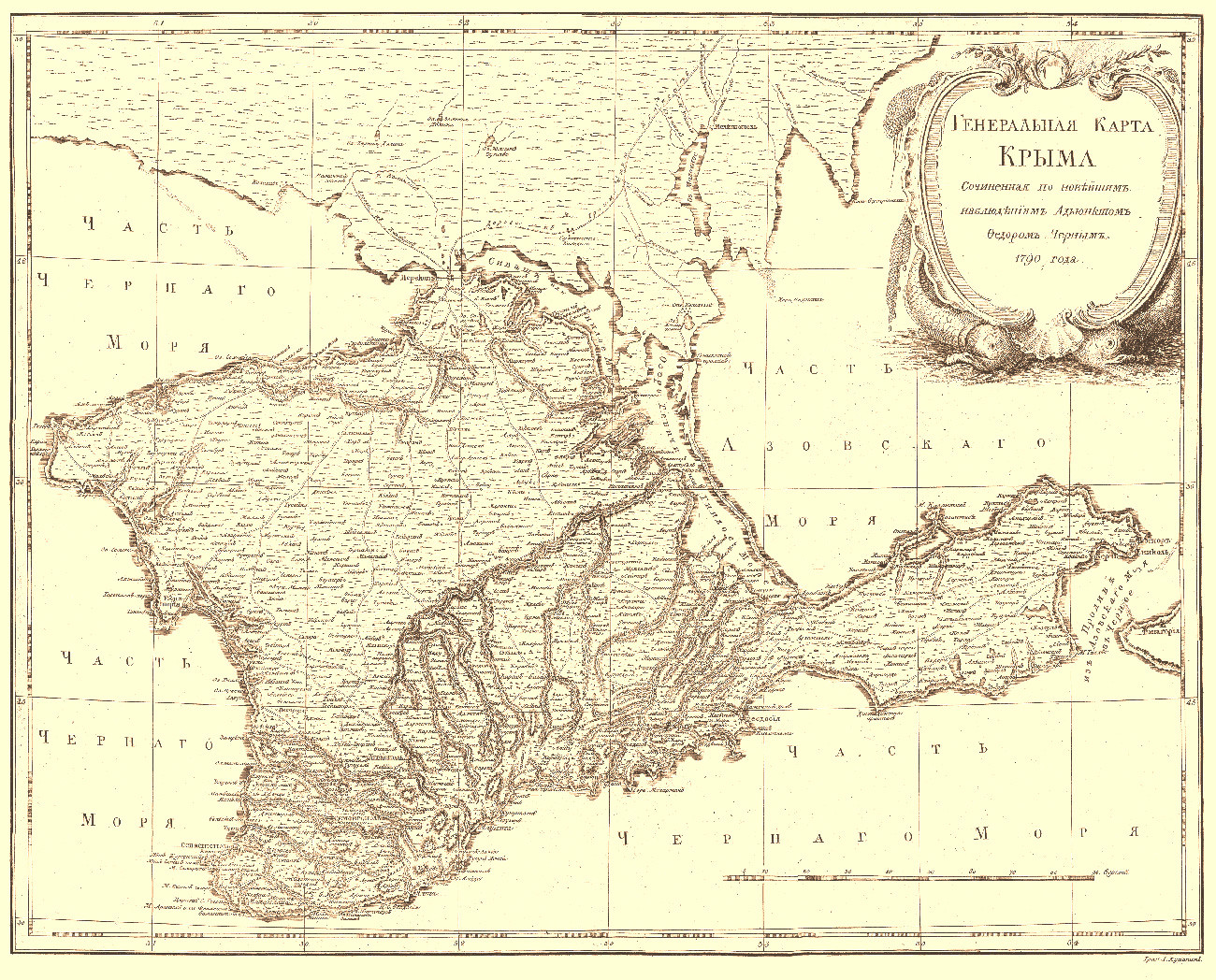

The Crimea on 1790 map

Public domainAs a governor of Novorossiya, Potemkin developed a plan to conquer neighboring Crimea. After the 1774 victory over the Ottoman Empire, in which Potemkin played no small part, under the peace treaty, the Crimean Khanate was declared a free state. Yet, the Turks were in no hurry to withdraw their troops from there. Under Potemkin's leadership, over many years, the Russians managed to – without shedding any blood – reach an agreement with the Turks and with the population of Crimea on the latter's merger with Russia. In 1783, on the flat top of Mount Aq Qaya, Grigory Potemkin personally received an oath of allegiance to the Russian crown from the Crimean nobility and common people. For joining Crimea to the Russian Empire, Potemkin was awarded the rank of field marshal.

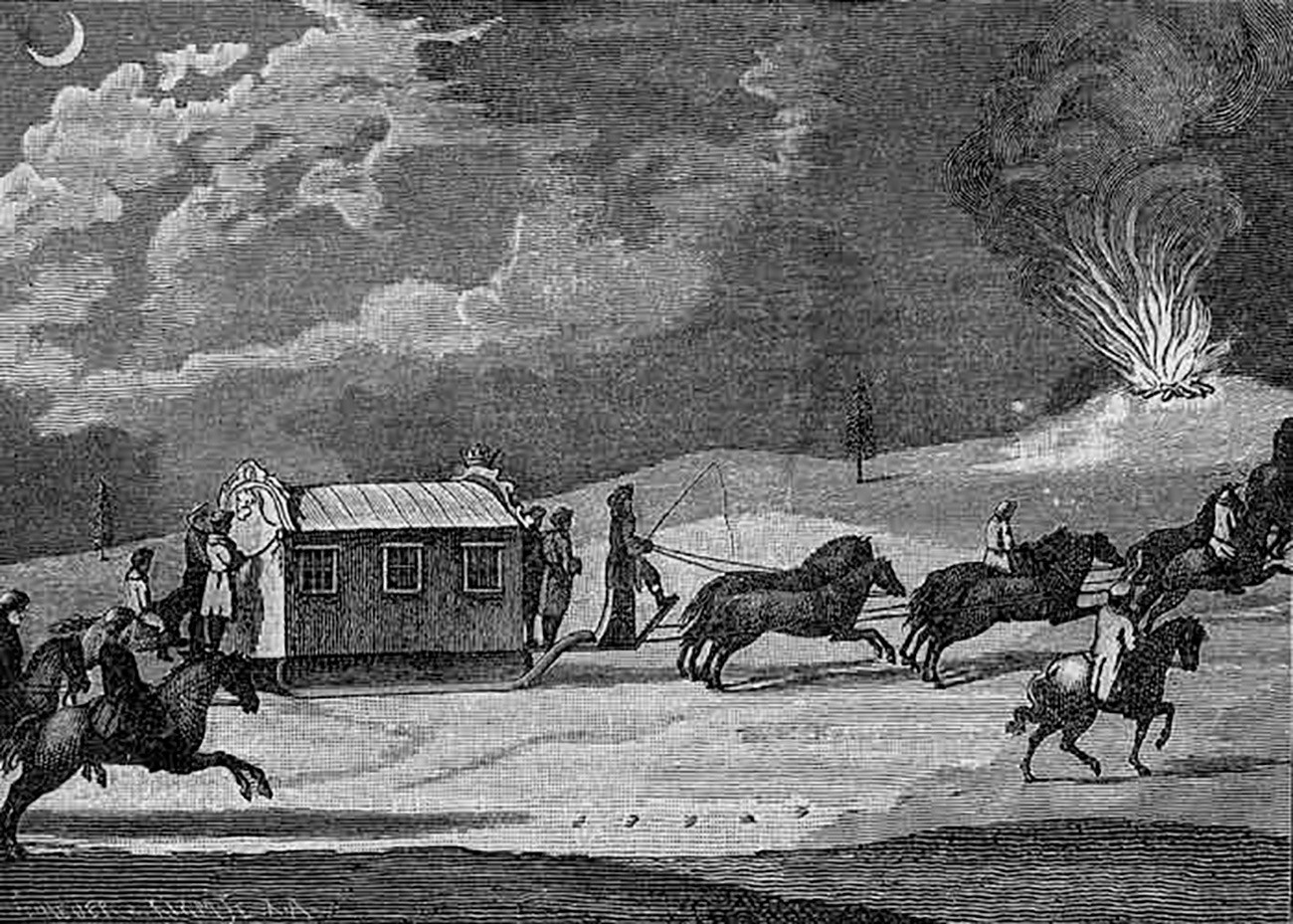

Catherine's imperial carriage during her Crimea journey in 1787

Hermann GoppeIn 1787, Potemkin took the 57-year-old empress to Crimea. In terms of scale, it was an incredible event. Catherine was accompanied by the whole court, some 3,000 people! The imperial procession consisted of 14 carriages, 124 sleighs with wagons and 40 spare sleighs. Catherine rode in a carriage for 12 people, pulled by 40 horses, where she was accompanied by courtiers, servants, as well as representatives of foreign diplomatic missions.

Fireworks in honor of Catherine the Great in the Crimea in 1787

Jan Bogumi Plersz/Lviv Art GalleryThe empress’s route (the journey began in winter) was lit by torches or burning barrels almost the whole way. At all major stops, she was met by governor-generals, and in Crimea, Catherine was joined by the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Joseph II. The empress spent 12 days in Crimea. After this journey, she granted the prince the title of Potemkin-Tauricheski.

Catherine the Great and the 'Amazon company'

Public domainIn 1787, Potemkin told Catherine how valiantly Greeks living in Crimea had fought against the Turks, together with their wives. When Catherine doubted the story, Potemkin promised to present the empress with evidence of the courage of those women - and ordered the formation of a company of 100 female warriors. The order was given to the head of the Balaklava Greek Battalion, which consisted of Greeks who had fled from the oppression of the Ottoman Empire. It was those soldiers' wives and daughters that made up the ‘Amazon Company’, which was headed by 19-year-old Elena Sarandova, the first female officer in the Russian Empire.

The ‘Amazons’ received intensive training in riding, fencing and shooting. On May 24, 1787, the Amazon Company met Catherine in the village of Kadikey. Riding their fine horses, the ‘Amazons’ were dressed in colorful uniforms: crimson velvet skirts and green jackets, both trimmed with golden galloons. Their heads were covered with white turbans with gilded sequins and ostrich feathers. And the empress was very pleased with what she saw. The Amazon Company accompanied Catherine on her journey through Crimea and was disbanded after the voyage was over. The Russian Amazons never took part in any battle.

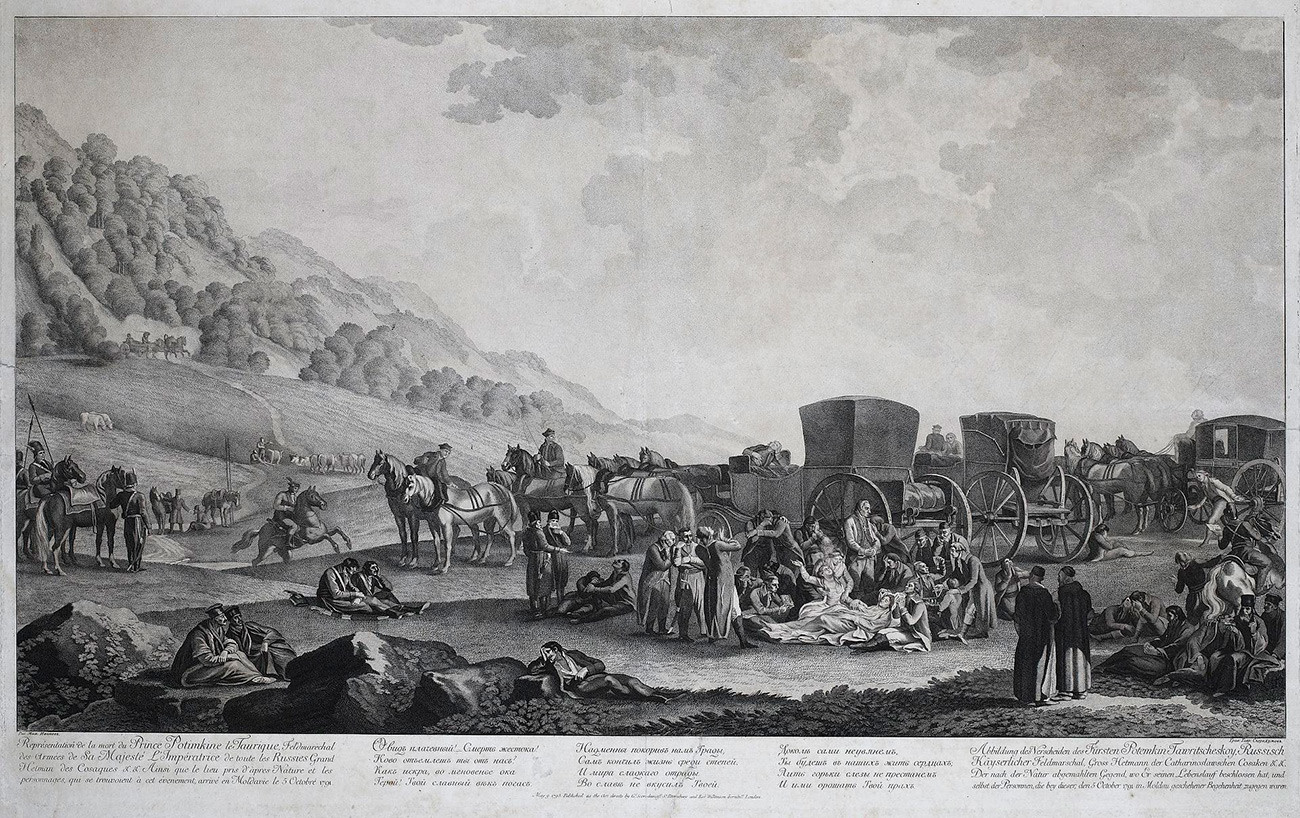

The death of Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski in a Bessarabian steppe

Public domainIn 1791, Potemkin, who was 52 at the time, was conducting peace negotiations with the Turks in the city of Iași, concluding yet another war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. On the way from Iași to Nikolaev, Potemkin suddenly became ill. He ordered to be carried from the carriage and died practically in an open field.

Catherine was devastated by the news of Potemkin's death. “My student, my friend, one might say, my idol, Prince Potemkin-Taurichesky has died!” she wrote. Potemkin’s ashes were buried in St. Catherine’s Cathedral in Kherson.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox