In every Soviet food store one could almost always buy butter and oil, tomato or birch or apple juice, dried kissel [fruit juice thickened with starch], canned food, cereals, cookies and pasta. But one could almost never find sausage, cheese, fresh meat or fruit and, in particular, “exotic” bananas. It was regarded as desirable to have a store manager among your friends, who could always “get a hold of” something from “under the counter”.

A store in Velikiy Ustug, Vologda Region.

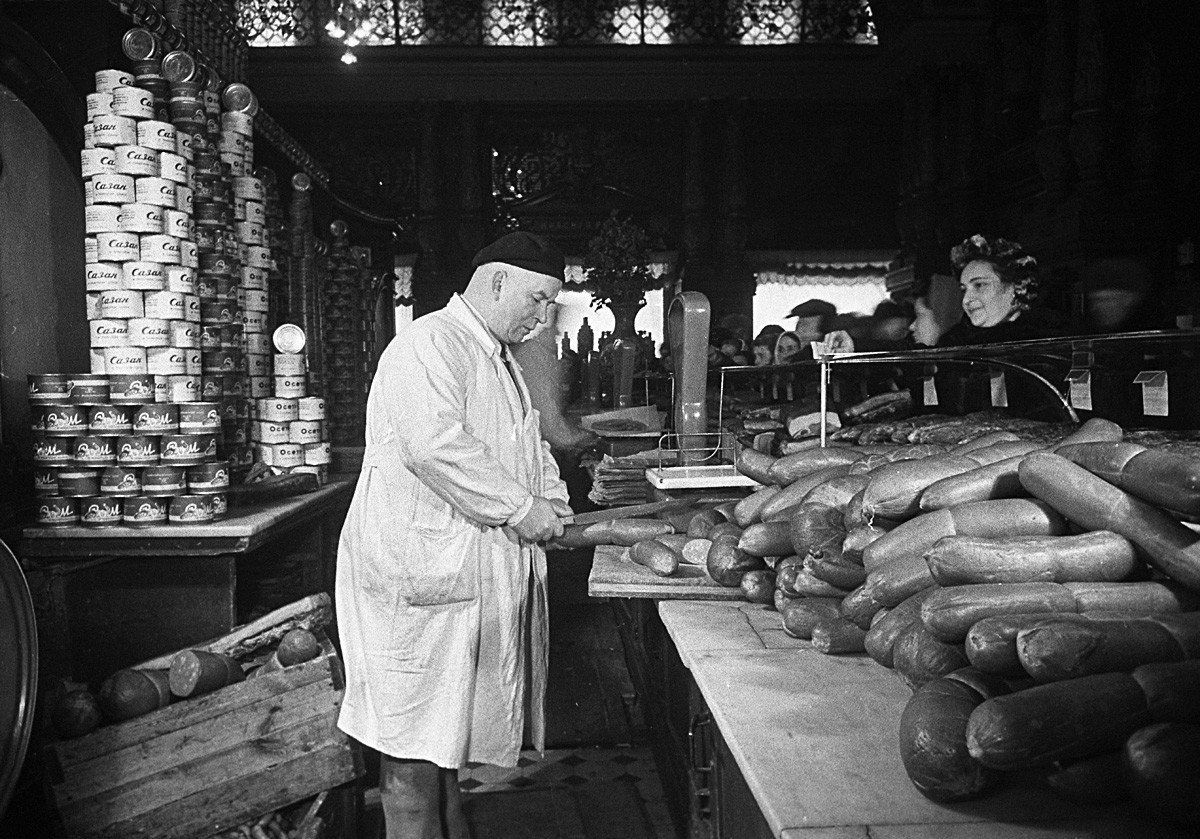

Yuryi Abramochkin/SputnikIn Moscow, the best grocery store was Yeliseyevsky (it was called Grocery Store No. 1 at the time) on the main thoroughfare, Tverskaya Street. It always had chocolates, ground coffee and even salmon roe and sturgeon caviar on its shelves. Even people from the provinces used to come here specially. Leningrad had its own equivalent, Vostochnyye Sladosti (Eastern Delicacies) - customers lined up here to buy Turkish delight and other culinary delicacies.

Sausages sold at Yeliseyevsky store in Moscow, 1951.

Anatoliy Garanin/SputnikTo deal with shortages and profiteering, Soviet authorities periodically introduced ration stamps. It meant that, apart from money, one would need to have a permit to buy certain goods. All in all, there weren’t many “ration stamp periods”: Between 1929-1934, there were ration stamps for buying bread, in 1941-1947, a few more food products required ration stamps, and, in the late 1970s, some regions even had ration stamps to buy sausage (mainly in the Urals region).

April 24, 1989. A queue of customers waits for open sale of goods at the Antey shop in the center of Saratov.

Yuri Nabatov/TASSShortages were at their peak towards the end of the USSR: In 1989, coupons were introduced everywhere for buying sugar, butter and oil, cereals, alcohol, soap and washing powder, etc. The sale of alcohol was limited to one bottle of vodka or wine per person per visit.

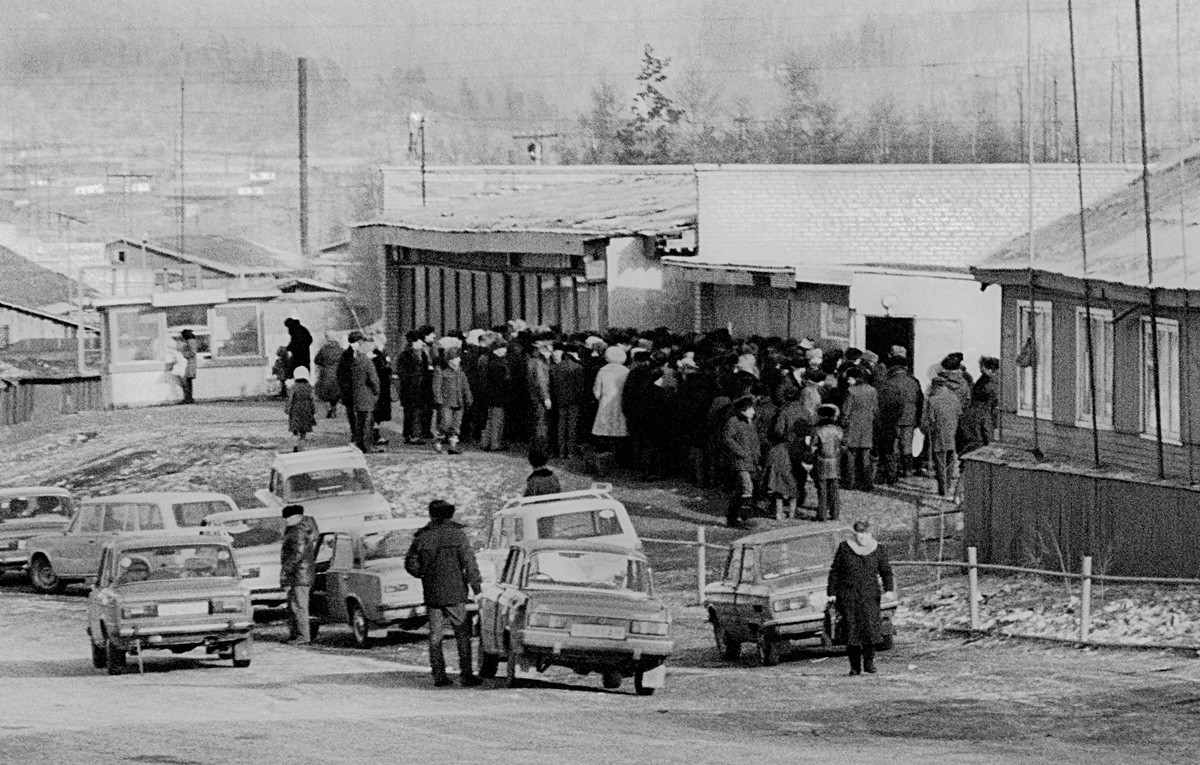

A queue outside a liquor store, Tynda (the Far East), 1988.

Vladimir Mashatin/SputnikPeople in the Soviet Union were among the most voracious readers in the world, but one could not find even innocuous adventure novels or good editions of fairy tales in the bookstores. Collected works of Russian and foreign classics, foreign detective stories and art albums were the books that were most in demand.

A bookshop on Kuznetsky Most Street, Moscow, 1981.

Viktor Chernov/SputnikIn 1974, special book coupons were introduced in the USSR in exchange for recyclable waste paper: For 20 kilos of old newspapers and magazines one could get one coupon that could be exchanged in a shop for a book that was in short supply.

A book fair in the Yaroslavl Region, 1981.

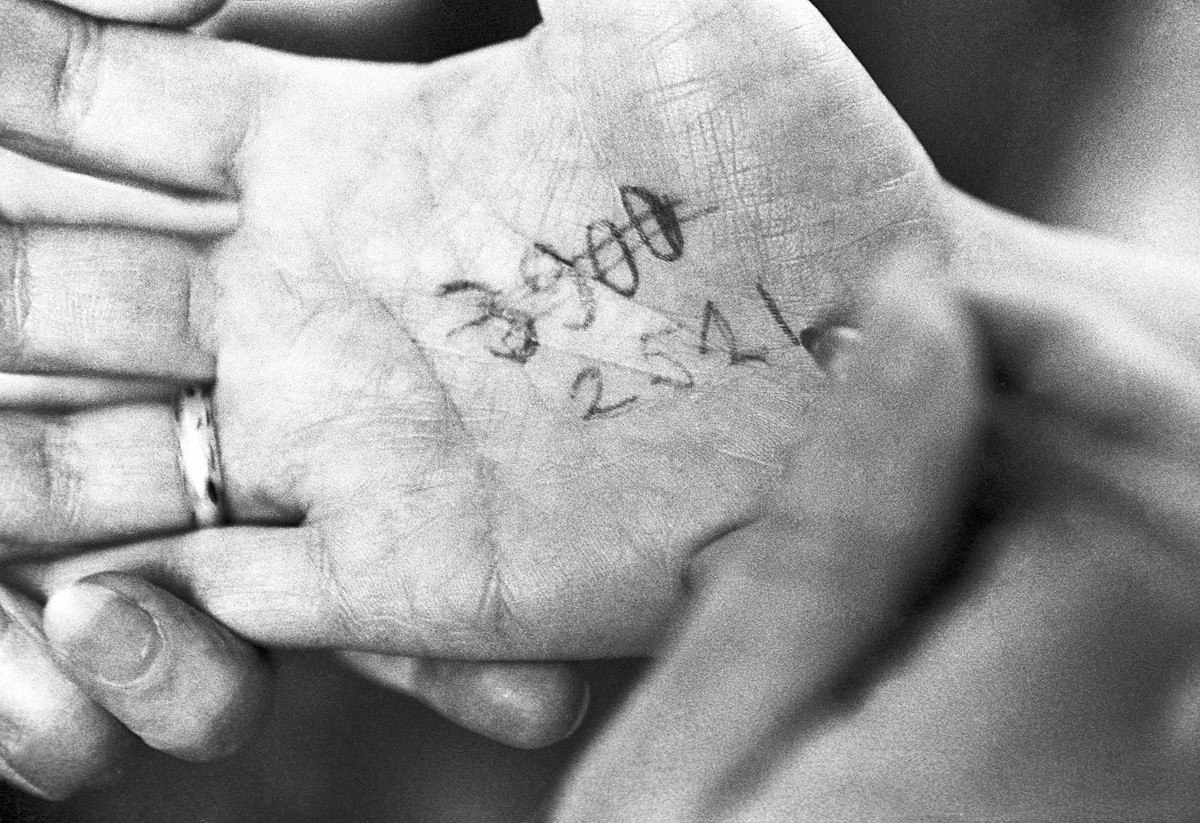

Sergei Metelitsa/TASSYes, it did happen - probably even most often. A person would be walking down the street, would see a line and join it - if people are getting in line, the shop must have “released” some goods, and it must be something worthwhile.

A queue number on the palm of someone’s hand.

Sergei Mamontov/TASS“Spring 1987. Imported trainers were shipped to Murmansk,” blogger Konstantin Shcherbin recalls. “Unfortunately, I learned about it too late, on the second day. I got a place in the line, somewhere in the seventh hundreds. I went twice to have my name on the list confirmed. After a day of standing in line, I moved forward by about 300 places. In the end, I ended up without any trainers.” There were stores that “released” goods more than others - for example, GUM on Red Square, the country’s best-known department store. People used to travel here from all over to buy goods that were in short supply, from sausages to fur coats. But lining up was no guarantee you would end up making a purchase. You could line up all night and still end up with nothing.

GUM, a large shopping mall in downtown Moscow. 1990.

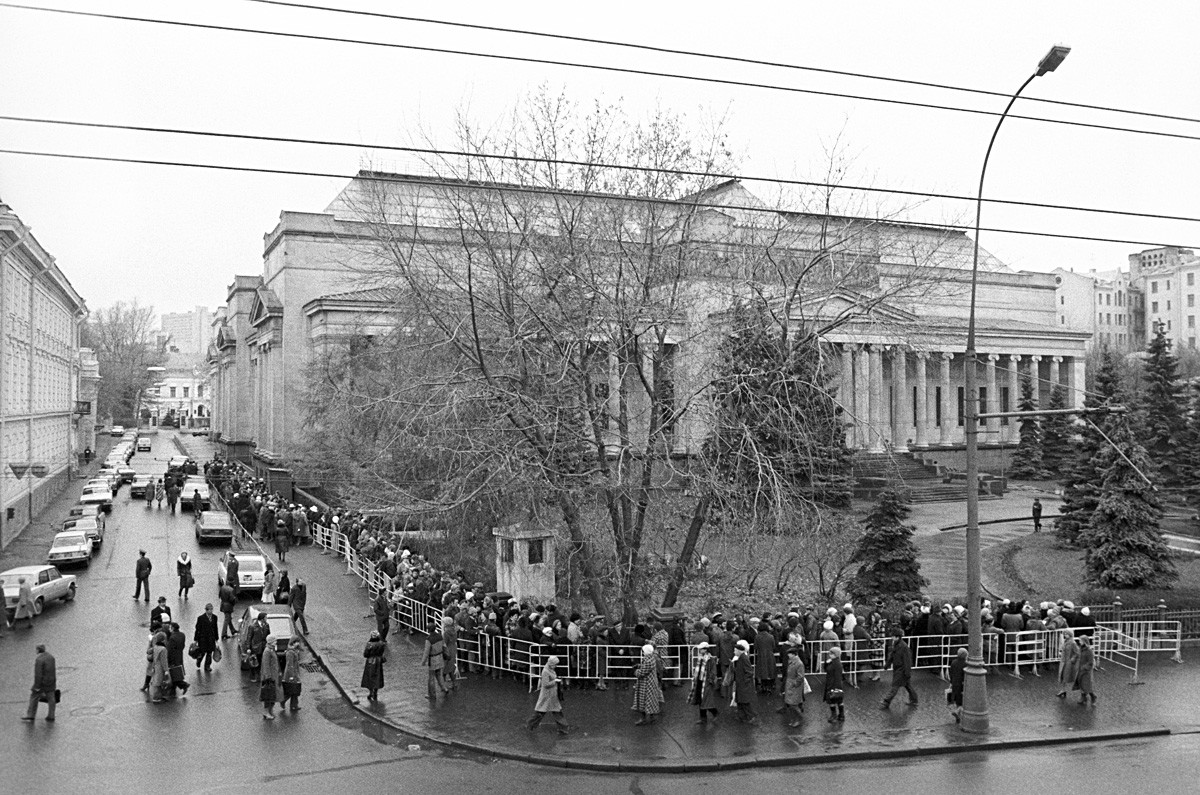

Vladimir Vyatkin/SputnikIt was rare that a tourist in Moscow or Leningrad didn't have to stand in enormous lines queues to get into museums or theaters, especially during special exhibitions. Many people described the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow as a “window onto the outside world”: Only here could one see world-famous art from abroad, both contemporary and classical. “We could not travel abroad. We had no idea what the Prado, or the Louvre, or the galleries in Florence or Milan were like. The Pushkin museum used to feed us information and exhibitions which made their way here with great difficulty,” recalled the editor of the Ogonyok weekly magazine, Vitaly Korotich.

Mona Lisa in the State Pushkin Fine Arts Museum, 1974.

Alexander Konkov, Valentin Cheredintsev/TASSIn 1974, the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts put on display Leonardo da Vinci's most famous painting, the Mona Lisa - it arrived in the USSR en route from Japan and stayed in the Soviet Union for two whole months. People would line up for up to 15 hours “on improvised benches, with sandwiches and thermos flasks, some reading and some dozing, in order to view the Mona Lisa for 15 seconds, which was the allotted time”, Ogonyok wrote about the exhibition.

In 1980, masterpieces of Spanish art from the Prado Museum in Madrid were brought to Moscow, including works by El Greco, Velázquez and Goya. Those who wanted to see the legendary works stood for hours in a long line that snaked around the museum.

People lining up to see the exhibition "Masterpieces of VI-XIX Century Spanish Painting from the collection of El Prado, Madrid" in the State Pushkin Fine Arts Museum, 1980.

Boris Prikhodko/SputnikArguably the most famous queue in Moscow (which exists to this day) is for the Lenin Mausoleum. Since it was built in 1924, it has been visited by 120 million people.

A line to the Lenin's Mavzoleum, 1961

Ivan Shagin/SputnikThe last stampede in the USSR was the line to get into the first McDonald's restaurant in Moscow, on January 31, 1990. Over 30,000 people came on the opening day, many of them having lined up since the previous night. Thus, the fast food chain's previous record, set in Budapest, where just over 9,000 people came to buy a burger on the first day, was beaten. It is known that the first visitors to McDonald's in Moscow received badges and small flags with the McDonald's logo as mementos.

Hundreds of Muscovites line up around the first McDonald's restaurant in the Soviet Union on its opening day, January 1990.

AP“The night before it opened, my friends and I walked from our student digs to Pushkinskaya Square. When we arrived, there were already three people standing there. While we were contemplating whether we should wait until the opening or not, two more people came. I took sixth place in the line. And I stood there until it opened. Since then, I've been a fan of McDonald's,” recalls blogger Konstantin Shcherbin. The lines only reduced, but not by much, after more McDonald's restaurants opened in Moscow.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox