By mid-1943, the war was swinging in favor of the anti-Hitler coalition. The Germans had suffered crushing defeats at Stalingrad and Kursk, and the Japanese had been routed in the battles of Midway and Guadalcanal. The Axis powers knew they were on the back foot.

Unable to reverse the dire situation, the Nazis opted for a different strategy — decapitate their three main opponents in one stroke. The decision was made to take out the entire leadership of the USSR, the UK, and the U.S.

The idea was conceived after German intelligence deciphered a U.S. naval code in September 1943, and learned of Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill’s intention to hold a conference in Tehran the following month (according to other sources, the leak occurred at the British embassy in Turkey). The Germans could not miss such an opportunity.

Soviet military officer raises a flare pistol, while standing in the Iranian desert.

Public domainThe considerable distance to Iran was no bother at all, since the country was familiar territory to them. Back in the 1930s, Germany had set up an extensive agent network there. The Iranian authorities were on friendly terms with the Nazis, who in turn felt at home there up until the German attack on the USSR. But by August 1941, Soviet and British troops had already entered Iran, effected a bloodless regime change, and ensured that the country would join the anti-Hitler coalition.

Overnight Tehran went from being Berlin’s ally to enemy, at least officially. But the German spy network, although down, was not out. Having gone underground, it resurfaced on the eve of the Tehran Conference, when Hitler gave the go-ahead for Operation Long Jump.

The operation to eliminate the three world leaders was placed in the hands of SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny, the Third Reich’s top saboteur and the liberator of Mussolini.

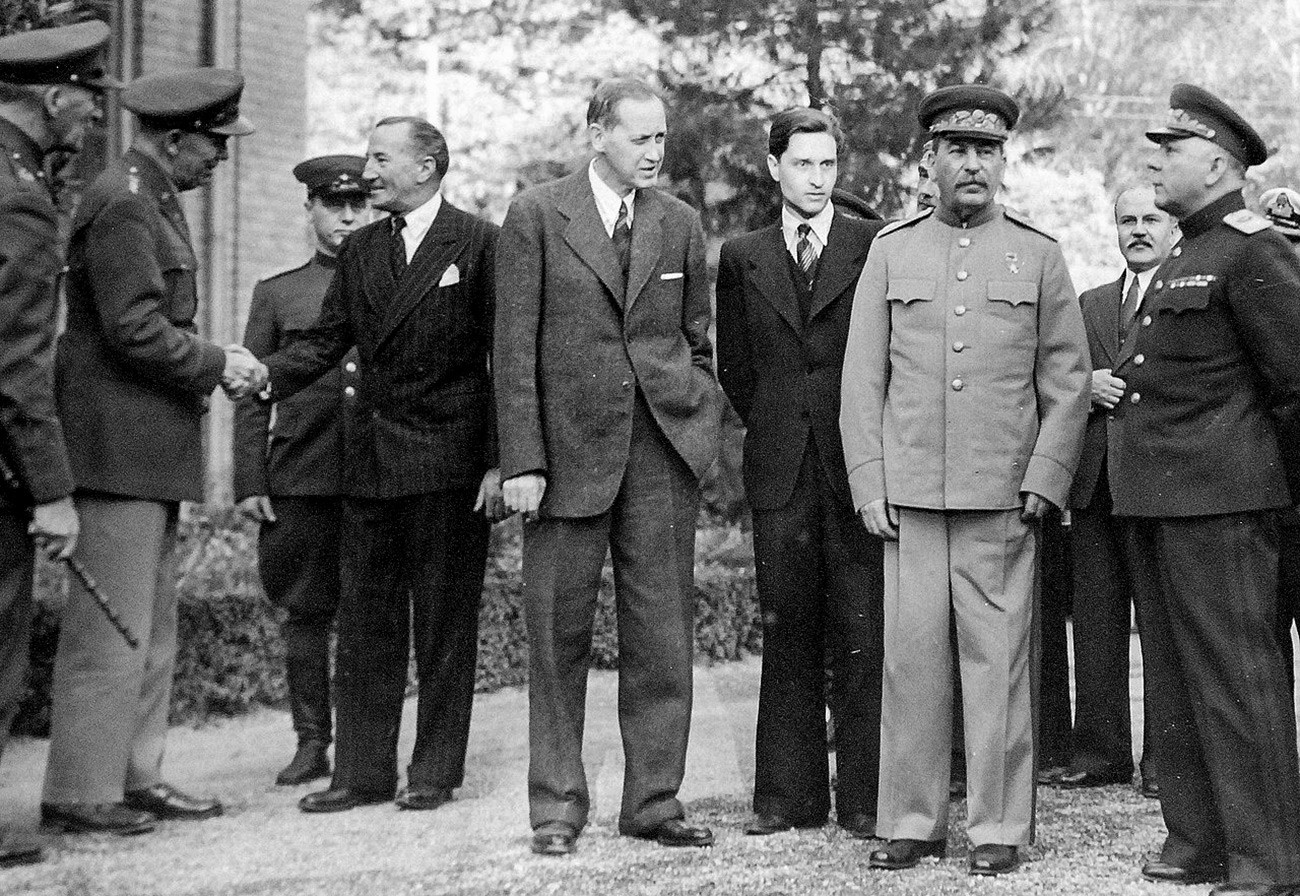

Left to right: Unidentified British officer; General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff, USA, shaking hands with Sir Archibald Clark Keer, British Ambassador to the USSR; Harry Hopkins, Marshal Stalin’s interpreter; Marshal Josef Stalin; Foreign minister Molotov; General Voroshilov.

National Museum of the U.S. NavyAccording to the plan, German sabotage units, having landed in Iran, would infiltrate Tehran, mix with the crowd, and lay an ambush. In those days, European faces drew little attention in the Iranian capital, since the city was full of refugees from war-torn Europe.

“Well-dressed [Europeans] either drove in chic limousines or simply sauntered along the sidewalks. They were wealthy refugees from war-torn Europe who had managed to transfer their capital to Tehran in good time and lived comfortably there. Of course, there were fascist agents among this crowd,” recalled Boris Tikhomolov, the pilot who flew Stalin to Iran.

The Germans knew that while the British and Soviet diplomatic missions were located next to each other, the American embassy was out in the outskirts of the city. Roosevelt, who faced traveling through the narrow streets of Tehran several times a day to get to the meetings, thus became the primary assassination target, or, if luck had it, he might even be captured alive.

Otto Skorzeny.

Public domainThe first group of saboteurs — six agents, including two radio operators — was parachuted in near Qum, 70 km from the Iranian capital. After infiltrating Tehran, its task was to establish radio communications with Berlin and to prepare the way for subsequent groups. Within two weeks, the saboteurs had made their way to a safe house set up by local agents.

However, Soviet intelligence too was not sat idle. Soon Stalin began to receive information from various channels about a possible attempt on the lives of the Allied leaders.

The main source was the agent Nikolai Kuznetsov. He spoke German well enough to pose as Wehrmacht Lieutenant Paul Siebert. Back in the city of Rivne in Western Ukraine, he had made friends with SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Ulrich von Ortel, who, during a drinking bout, had spilled the beans on the forthcoming operation.

Nikolai Kuznetsov.

SputnikStalin flew to Tehran already well informed of the German plans. For a start, security was seriously beefed up, and known German agents were cleared from the city. Roosevelt was even invited to stay at the Soviet embassy, next to the meeting room, for security reasons. The president gladly agreed, partly because his leg paralysis made traveling difficult.

It wasn’t long before SMERSH (Soviet counter-intelligence) uncovered the first sabotage group, which was neutralized even before the conference began. As soon as Berlin found out, the mission was canceled. Operation Long Jump had fallen headfirst in the sand.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox