All Russian monarchs were human, meaning each of them had their own quirks and vices which they couldn't or wouldn't get rid of. Habits should not be confused with hobbies: For example, going hunting regularly was a hobby for many tsars, but only one of them was crazy about smoking a hookah pipe.

Original: Portrait of Catherine the Great in the 1770s by Ivan Sablukov

Public domainEmpress Catherine II (1729-1796) was an inveterate coffee junkie. She began each morning with two small cups, each of which had five or six teaspoons of ground coffee! The dregs remaining after the Empress's coffee ceremony were passed on to the servants, who made an aromatic drink from them two or three more times.

In the 18th century, coffee was considered to be an exclusively male beverage and in regularly drinking coffee Catherine emphasized that she was no worse than any man. There is a story that once, with the Empress's permission, state secretary Sergei Kozmin tried the coffee brewed for her. His heart rate went up so much that he needed a doctor.

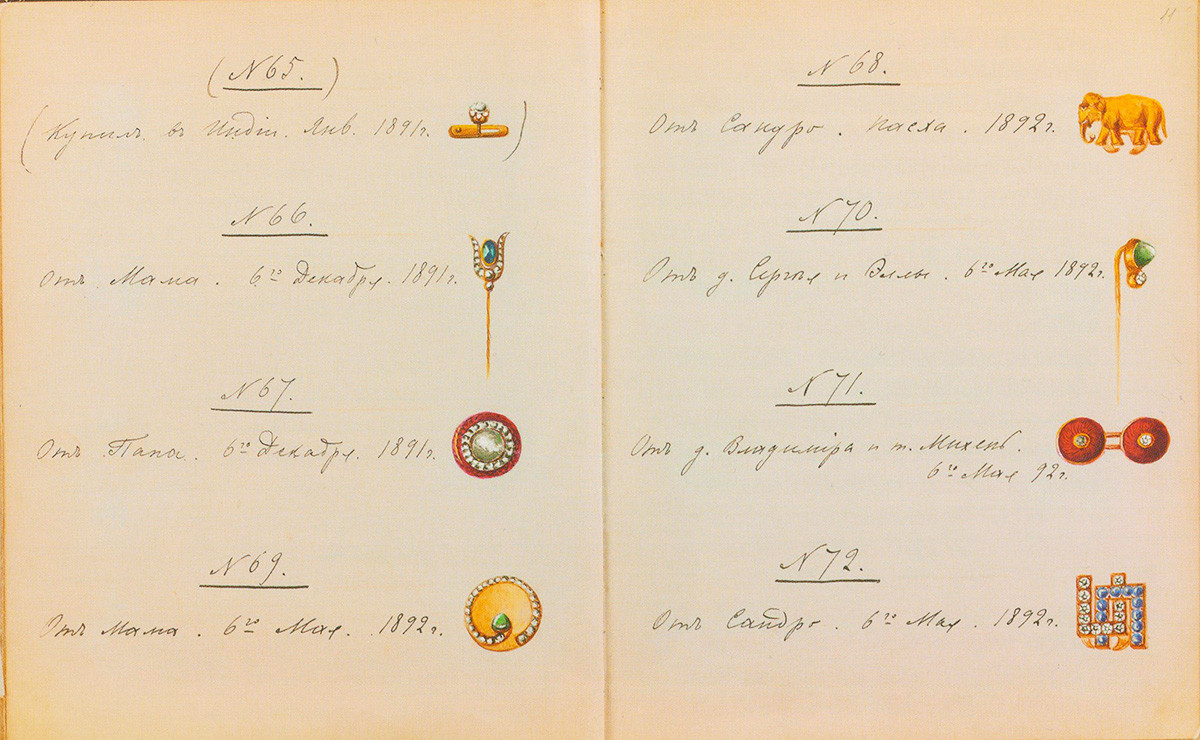

Pages from Nicholas's jewelry album

Public DomainWhen writing about what the last Russian Emperor liked to get up to, historians usually mention cycling, tattoos, hunting, and lawn tennis... However, all these were simply Nicholas II's (1868-1918) hobbies. As for his habits, smoking is worth mentioning - Nicholas himself smoked a lot (over 25 cigarettes a day) and he would also secretly teach his daughters to smoke.

Truly amusing was Nikolai Alexandrovich's obsession for keeping an inventory of all the jewelry he received as presents. There are 136 pages in the Jewelry Album of Nicholas II, 41 of which are filled with drawings of jewelry in ink, chalk and bronze paint. The album was started in 1889, when Nicholas was 18 years old. Most of the drawings were done by Baroness Tiesenhausen, an elderly lady-in-waiting at the imperial court. The Emperor made sure that all the knick-knacks he received as presents were entered in the album, and he signed each of them. He didn't stop the habit even during World War I.

Portrait of Emperor Nicholas I (1796-1855) in Austrian Uniform, the 1840s

Getty ImagesNikolai Pavlovich (1796-1855) was the only Russian Emperor who never smoked, was indifferent to alcohol, preferred a Spartan diet and never ate anything sweet.

The “only imperial foible”, mentioned by many memoirists, was Nicholas I's “addiction” to pickled cucumbers. The Emperor started every day with them: For breakfast he was served tea, sweet and sour bread, and five pickles. The Emperor didn't eat supper, but in the evening he often drank a couple of spoonfuls of pickled cucumber brine. Yummy!

Peter III Emperor of Russia by Aleksey Antropov

Getty ImagesAs a child, the future Emperor and husband of Catherine II, Pyotr Fyodorovich (1728-1762) had a traditional Prussian upbringing, full of cruelty and restrictions. In fact, the Grand Duke didn't have anything resembling a normal childhood. It was perhaps for this reason that, when he was already a young man, he reverted to childhood games. Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein, a Prussian diplomat in Russia, wrote in 1748 when Peter was 20: “For several hours every day he plays with dolls and puppets, and those appointed to look after him hope that with age he will acquire profound ideas, but it seems to me they have been deluding themselves for too long.”

They started hiding the dolls from the Emperor, but it didn't help. Describing the time before her husband became Emperor, Catherine II wrote about “the toys, dolls and other childish things that he loved madly; during the day they were hidden in and under my bed. The Grand Duke went to bed first after supper and, as soon as we were in bed, Madame Kruse (a lady-in-waiting) locked the door with a key and then the Grand Duke would play until one or two in the morning. Like it or not, I was obliged to take part in this fine pastime, as was Madame Kruse.”

Tsar Alexander II of Russia, (1818-1881)

Getty ImagesAleksandr Nikolayevich (1818-1881), the Tsar-Liberator, inherited digestive problems from his ancestors. In 1850, while in the Caucasus, the Grand Duke tried smoking a hookah pipe and noticed that it helped to relax his intestines. After that, the hookah became an indispensable attribute of life for the Grand Duke and later Emperor. Count Peter Dolgorukov recollected: “His majesty, having sat where he sees fit, begins to smoke a hookah and smokes until this activity is a total success. Enormous screens are placed before the sovereign and behind these screens, persons gather who, by special royal favor, have been granted the highest honor of entertaining the sovereign during his smoking of the hookah and other activities.” During the reign of Alexander II, the court had Arab hookah makers among its specialist staff.

The Tsar used Persian tobacco and, to all appearances, liked his hookahs very strong and copious; every six months he ordered three puds (48 kilos) of tobacco, which comes to more than 250 grams a day (between 20 and 25 grams are needed for a single hookah session)! Alexander II additionally smoked cigars.

Portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna (1709-1762) by Ivan Argunov

Getty ImagesNowadays, a foot massage is part of a routine beauty treatment for relaxing and toning the body. From ancient times it was known as “heel scratching” and was very popular among the Russian provincial aristocracy until the end of the 19th century. In his story, The First-Class Passenger, Anton Chekhov ironically mentions a father who liked female serfs to scratch his heels after lunch. In Gogol's Dead Souls, Korobochka, when putting up Chichikov for the night, offers to send some peasants to scratch his heels. In both cases, the mention of the habit is a hint at the characters being backward country folk.

But Empress Elizabeth Petrovna (1709-1762), the daughter of the first Russian Emperor, acquired this peasant habit when she lived in Aleksandrovskaya Sloboda, an ancient estate of the Moscow princes. Elizabeth was forced to live there for some time at the beginning of the reign of her cousin, Anna Ioannovna [Anna of Russia] (1693-1740). While there, the princess didn't shirk from simple peasant work, spent a lot of time with the peasants, singing songs and dancing the khorovod (a folk dance) with them. She also got used to having her heels scratched before going to bed. She took this habit with her to St. Petersburg, when she became Empress. She entrusted this absolutely non-aristocratic task to her closest ladies-in-waiting - the wives of first chancellors, admirals and the most senior imperial counselors - and these ladies competed with each other for the high honor of giving the Empress this “beauty” treatment.

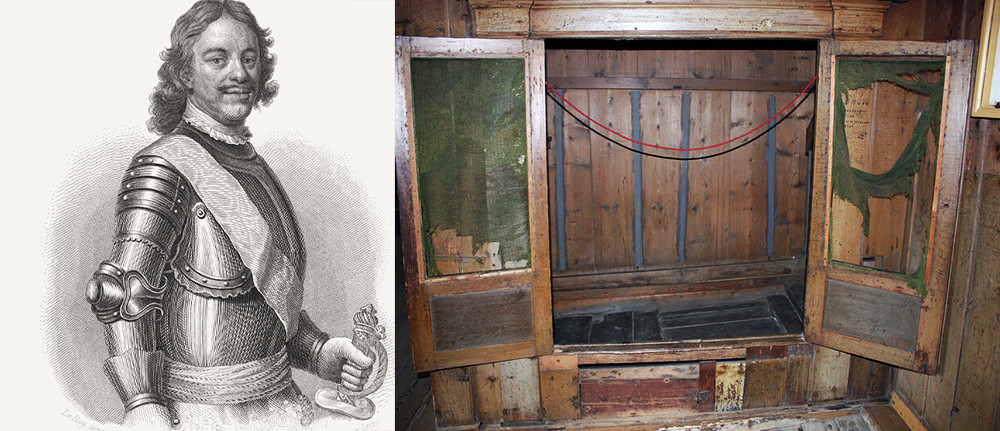

Peter the Great (L) and the cupboard bed he slept in, exhibited in Zaandam in Holland (R)

Getty ImagesPeter I (1672-1725), the reforming Tsar who transformed the life of Russian nobility by updating their traditional ways along European lines, spent his childhood in a genuinely old Russian atmosphere in a traditional wooden house in the village of Preobrazhenskoye, where he lived with his mother, Natalya Naryshkina. Traditional Russian houses had a large number of rooms, but the rooms were small and the ceilings in them low - it was easier to keep the house warm this way. When Peter was a little older, Poteshny Palace became his private residence. It, too, had small rooms, low ceilings, and doors.

Afterward, wherever Peter was staying, if he deemed the ceiling in a room to be too high, his servants stretched a piece of canvas they carried with them to make an impromptu suspended ceiling - Peter found it cosier that way. Despite his exceptional height, he was fond of cramped spaces. When he lived and studied shipbuilding in Zaandam in Holland, Peter slept, according to Dutch tradition, in a cupboard bed, which survives to this day and is a popular museum exhibit.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox