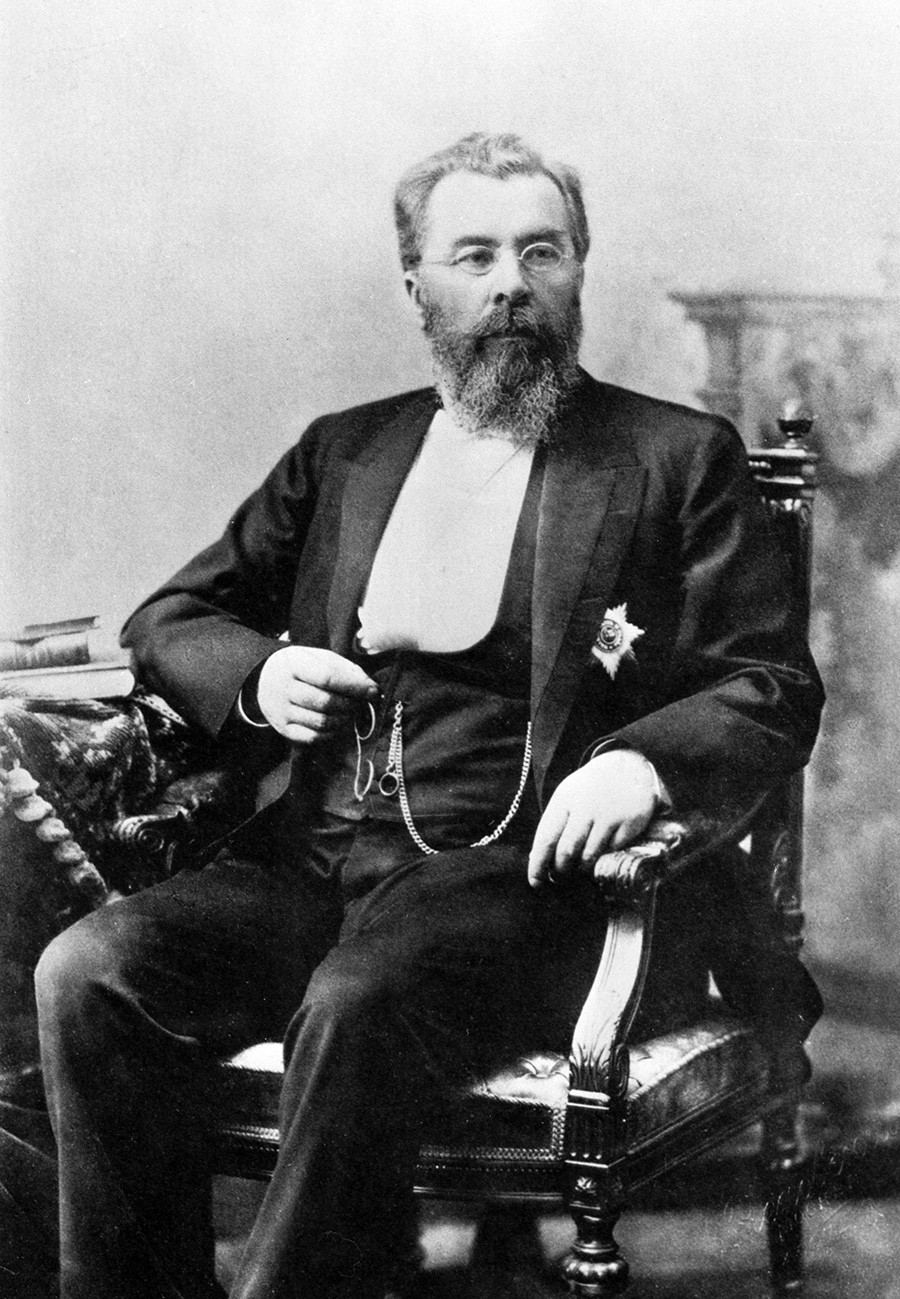

Surgeon Nikolay Sklifosovsky (1836-1904) saved hundreds of soldiers, whom he operated on during the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), the Balkan War (1876) and other military conflicts. However, his main legacy was the introduction of strict hygiene standards into medical practice. This may be hard to believe today, but because of insufficient cleanliness, many operations ended tragically, both for patients and for doctors, who could become infected. Antiseptic dressings soaked with alcohol and iodine were first used by Nikolay Pirogov, but it was his pupil, Sklifosovsky, who managed to introduce mandatory use of antiseptics, which at the time was not at all easy. Doctors in the late 19th century were set in their ways and very resistant to change: bandages were reused, medical instruments were simply washed in warm water, operations were conducted on wooden tables that absorbed patients’ sweat and blood. The introduction of new methods took Sklifosovsky years of scientific research and awareness-raising efforts: gradually surgical instruments began to be sterilized, used dressings were burnt, doctors started to wash their hands after each operation, and wooden tables were replaced with metal ones.

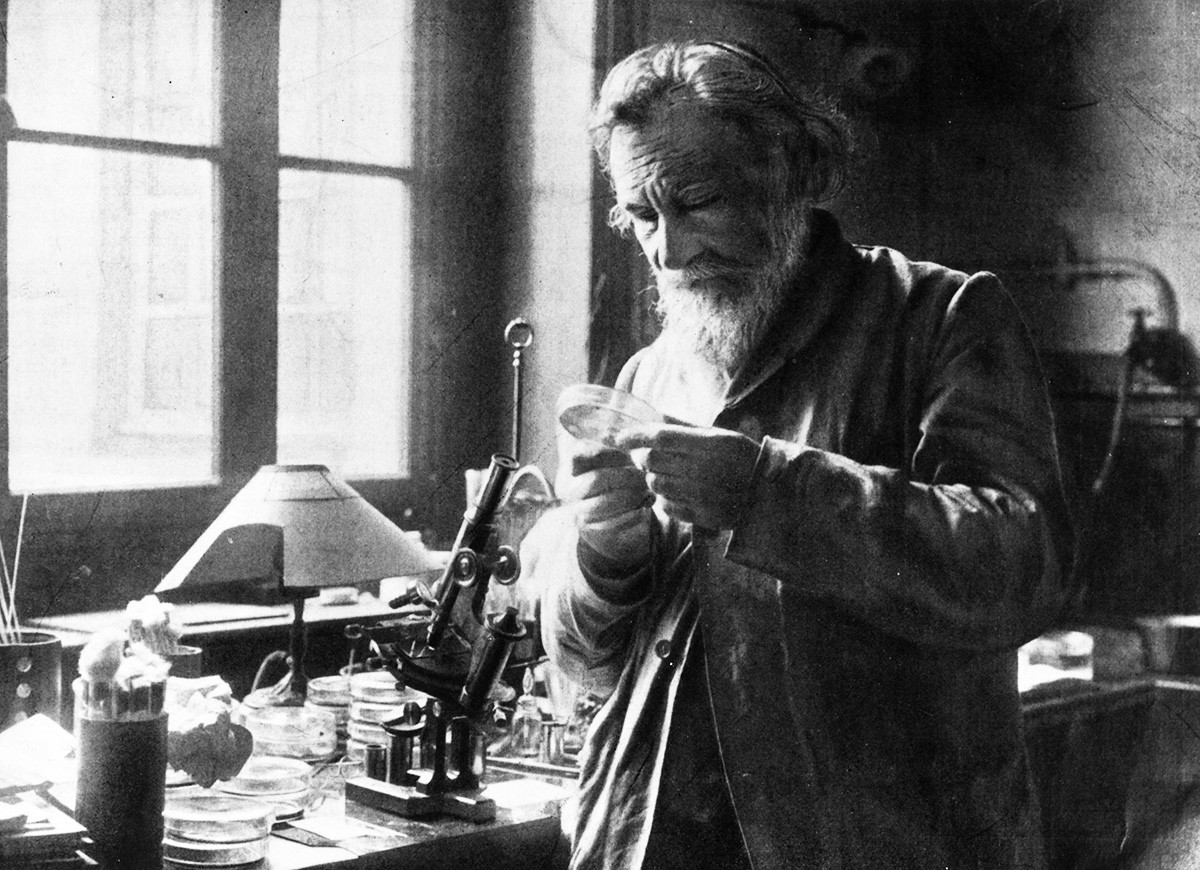

These days, we have almost forgotten about diseases such as typhoid or cholera, although just in the recent past they managed to wipe out entire villages. At what cost did doctors manage to stop those epidemics? Since ancient times, many doctors performed experiments on themselves in search of a cure. They deliberately infected themselves and did not allow anyone to treat them, in order to study the course of the disease and a body’s reaction to it. That was how numerous scientific discoveries in immunology and virology were made. From a young age, Ilya Mechnikov (1845-1916), the founder of the Russian school of immunology, loved to experiment and observe natural phenomena, for which his mother nicknamed him ‘Mercury’. In the Russian Empire, and later in France, he created vaccinations against rabies, cholera and anthrax. To test his own hypotheses about the spread of bacteria, he inoculated himself with syphilis, relapsing fever, and blood of a malaria patient, each time fighting for his life. Twice he drank cholera-infected water. Contemporaries said that what helped Mechnikov to survive in all these experiments was his exceptionally strong health. To the end of his life, he studied the issues of longevity and concluded that a person’s health directly depended on the state of their intestinal microflora and, oddly enough, on their disposition. A happy person lives longer, and vaccinations help against diseases – we know these seemingly obvious things thanks to Mechnikov.

The incredible story of this Urals surgeon became known thanks to one of the people he saved, pilot Anna Yegorova, a Hero of the Soviet Union, who was shot down near Warsaw in 1944. In 1961, in an article in the Literaturnaya Gazeta newspaper, she told the story of a doctor who had helped her escape from a concentration camp. And not only her. During the Great Patriotic War, Georgy Sinyakov (1903-1978) managed to arrange for many prisoners of the Stalag III-C concentration camp in Poland to escape. Drafted in the early days of the war, he served as a front-line surgeon, until in October 1941, he was captured near Kiev. From May 1942 until almost the end of the war, he was a prisoner at Stalag III-C. According to one story, he saved the son of one of the Gestapo soldiers, who had choked on a bone, and the Nazis allowed the doctor to move freely around the camp and increased his daily food rations (which he shared with other prisoners).

One way or another, Sinyakov took advantage of his privileged position to help other prisoners escape. In that, he was assisted by a German interpreter, Helmut Schacher (who was married to a Russian). Schacher supplied prisoners with maps and compasses, while Sinyakov made sure that they were officially listed as dead. This is how it worked: Sinyakov pronounced a prisoner dead, the prisoner was taken out with the corpses of people who were really dead and dumped in a ditch outside the camp, where the prisoner then “rose from the dead”. At the beginning of 1945, when the Red Army was already approaching the camp, there remained about 3,000 prisoners in it. Sinyakov managed to persuade the Nazis not to kill the prisoners. It remains unknown how he did it, but the Germans retreated without firing a single shot. Soon the Soviet troops entered the camp, and in a matter of just a few days, Sinyakov operated on some 70 wounded Soviet soldiers. The doctor reached Berlin and left his signature on the walls of the Reichstag building. After the war, Georgy Sinyakov worked in a hospital in Chelyabinsk. He preferred not to talk about those years.

The operation conducted by Soviet doctors in September 1986 seems utterly unbelievable. Soldier Vitaly Grabovenko was wounded in the war in Afghanistan and was brought to a hospital in Dushanbe, the capital of the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic. He had multiple shrapnel wounds that were successfully sewn up. Only on the following day, when he could not move his arm, an X-ray showed a strange rectangular shape in his chest muscles. It was quite large, 11 cm in length. The doctors turned to the military for advice and several people confidently stated that this was a live piece of ammunition. One careless movement, and the whole hospital could explode. A similar incident took place during the Great Patriotic War, when a whole medical team was killed while trying to remove a grenade from a patient. Nevertheless, the decision was taken to operate.

The head of the hospital, surgeon Yuri Vorobyev, volunteered to conduct the operation. He was assisted by a young doctor, Lieutenant Alexander Dorokhin. Preparations for the operation took four days, with every action carefully planned down to a second. To extract the projectile, a special instrument was made that would make it possible to clasp it tightly. The hospital was cordoned off by mine disposal experts. There were medical teams on standby, in case the doctors got injured. The anaesthetic team was working in helmets and body armor. The surgeon and his assistant put on 30-kg blast suits and had bulletproof glasses covering their eyes. While the temperature was 40 degrees! The operation lasted 15 minutes - the extracted projectile was quickly put into a container and given to mine disposal experts. Vorobyev managed not only to successfully remove the dangerous piece of ammunition, but also to save the soldier’s arm. For his feat, he was awarded with the Order of the Red Banner.

“Children’s doctor of the world” - this is what Leonid Roshal (born in 1933) is known as, both in Russia and abroad. He was always there where children were in need of help: Roshal saved children’s lives after the earthquakes in Armenia (1988) and Afghanistan (1998) and the wars in Iraq (1991) and Chechnya (1995). In 2002, when terrorists seized the Dubrovka Theater Center in Moscow, he was one of the few people who were allowed to go inside. The doctor was able to hand over water and medicines for the hostages and persuaded the terrorists to release eight children.

Two years later, he had to witness one of the worst terrorist attacks in Russian history: on September 1, 2004, in the small town of Beslan, terrorists seized a school with more than 1,000 pupils and their parents in it. Roshal was the first one whom the terrorists demanded to see. He arrived at the scene a few hours after the attack began. In Beslan, he was given a phone and he had about a dozen conversations with a terrorist, whose name he did not know, trying to persuade him to at least allow water to be passed to the children. By September 3, an agreement was reached to remove the dead bodies lying in front of the school. At that time, an explosion was heard inside the school, and the hostages started running out of the building, jumping out of the windows, while the special forces began to storm the building. Roshal later recalled: “Perhaps the most important thing that I did in my life was that I managed to stop hundreds of the hostages’ relatives from trying to free their children themselves. The terrorists would have thought that it was an act of provocation and there would have been a massacre!”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox