There were Russian people who chose death rather than give up their faith. The harsh tradition of collective suicides by fire was born among the Russian Old Believers in the 17th century and continued into the 19th century.

"Self-Immolators," 1882, by Grigoriy Myasoyedov

Grigoriy Myasoyedov“With a heavy thud of the explosion, the ground shook and everybody felt a blast of air to their chests. Smoke appeared between the cracks of the roof, and then, more thicker smoke… The flames leapt between the logs of the hut. When soldiers burst through the door, a man caught in flames fell out, his head burned black. He rolled on the snow like a worm. Inside the prayer house, smoke and fire was swirling, and burning people staggered to and fro. The fire was coming from the basement. [...] The soldiers took a few steps back because of the unbearable heat. Apparently, no one could be saved. The soldiers crossed themselves, having taken off their three-cornered hats, some were crying. [...] And one had nowhere to hide from the smell of burned flesh.”

This is how Alexey Tolstoy describes an episode of self-immolation in his novel “Peter the First.” The self-immolations of Old Believers in Russia started during the reign of Peter’s father, tsar Alexey Mikhailovich (1629-1676), because of religious reforms initiated by the tsar and Patriarch Nikon (1605-1681). The self-immolations soon gained a unique name, гари (‘gari,’ singular гарь, ‘gar’’), which roughly means ‘burn.’

Patriarch Nikon (Nikita Minov)

Public domainIn 1596, the Kievan Metropolis broke off relations with the Russian Orthodox Church and entered into communion with the Pope of Rome. The Orthodox Churches of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth became Greek Catholic churches. This was a harsh blow for the Russian Orthodox church that lost parishes, territories, and money. By the mid-17th century, Russian patriarch Nikon decided to reform the Russian Orthodox church.

Patriarch Nikon invited Catholic scholars from Kiev to correct the Russian liturgical books that had many mistakes compared to their Greek originals – they were copied and re-copied by Russian monks for centuries and needed updating. Historians are not sure what was Nikon’s eventual goal, maybe he, too, wanted the Russian Orthodox church to enter into communion with the Pope. What was important is that this reform led to the Raskol (the Split) – the splitting of the Russian Orthodox Church. Two fingers raised before making the sign of the cross became the symbol of the Raskol. Why?

"The Boyarynia Morozova," 1887, by Vasiliy Surikov (1848-1916). Feodosia Morozova (1632 – 1675) was a noblewoman and a supporter of the Old Believer movement. Here she is seen with her two fingers raised in the Old Believers' way of making the sign of the cross. Morozova died in prison.

Vasily Surikov/Tretyakov GalleryIn 1653, letters from the Patriarch were sent to all the churches of Moscow, and subsequently, to all eparchies (provincial church branches) of the Muscovy Tsardom. These letters introduced new rules of liturgical services, and new, corrected liturgical books were printed and dispensed in the country. Nikon used the reform to strengthen his authority as the head of the renewed Russian church.

Among the most important liturgical changes, the two-fingered sign of the cross was changed to a three-fingered one, the name of Jesus changed its spelling on icons, and so on. For contemporary people, these changes could seem minor, but in the 17th century, they were crucial.

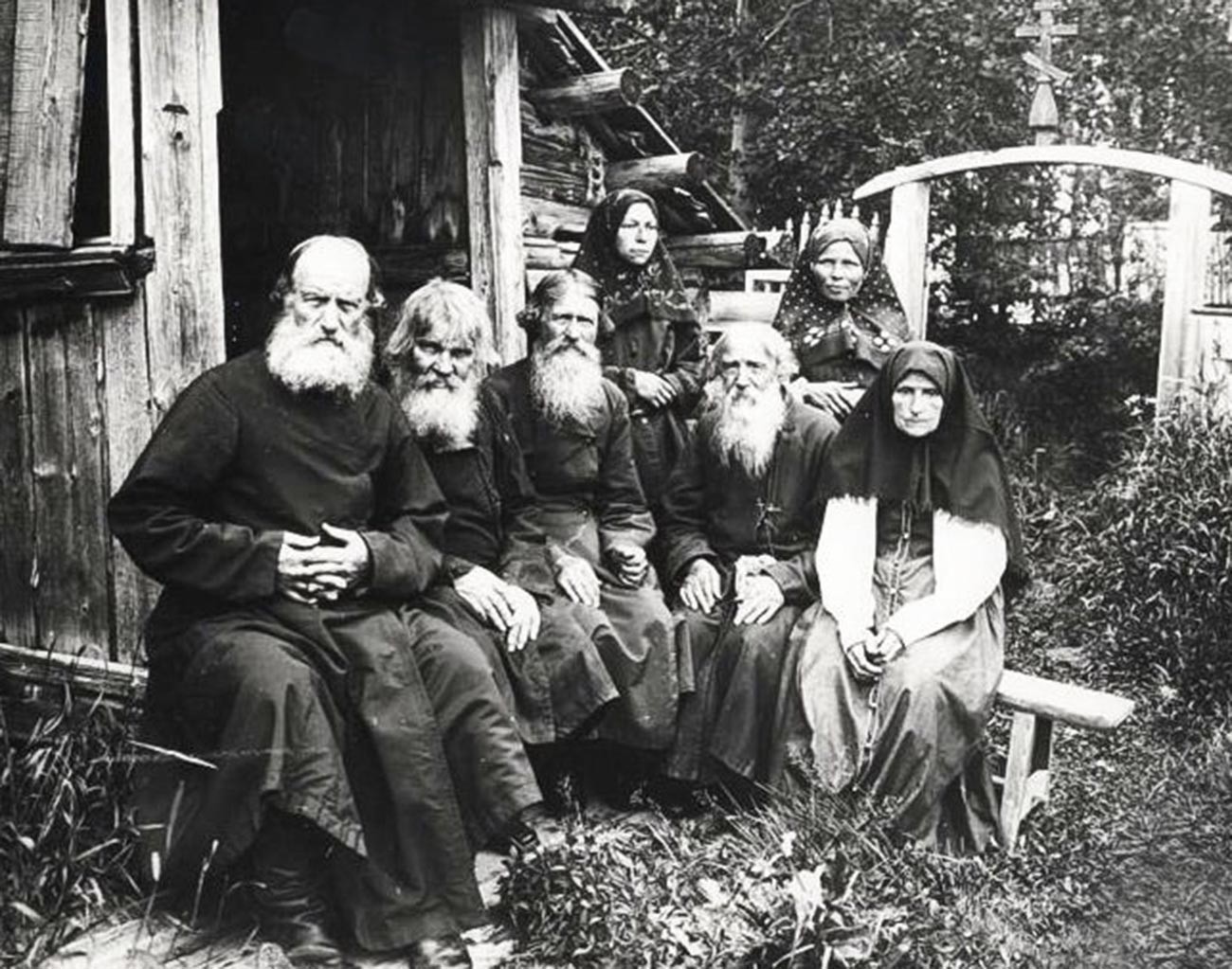

A group of Old Believers in the 19th century

Maxim Dmitriev/МАММ/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThose Russian Orthodox Christians who denied the reform as “devilish,” because Nikon’s changes messed with the most sacred symbols of religion, were called the Old Ritualists, or, commonly, the Old Believers. They were anathematized at the Great Moscow Synod of 1666 – this meant that these people could no longer take part in official Russian Orthodox sacraments. Moreover, they were double-taxed, banned from gatherings and organizing chapels. These actions of the official church were met by the Old Believers with the harshest response one could imagine, collective self-immolations.

"The Great Comet of 1680," by a Dutch artist Lieve Verschuier (1627-1686)

Lieve Verschuier/Museum RotterdamFor the Old Believers, it was no coincidence that they were anathematized in 1666. Although they counted their years from the creation of the world, they were aware of the fact that in the Julian calendar, this year was marked by the Devil’s Number. The Old Believers definitely saw this as a dark omen. But it wasn’t the only one.

“Cyril’s Book” was a compendium of religious texts, popular in the 17th century. It contained predictions about the End of Days that would happen “during the 8th millennium from Adam” (6999/7000 from Adam came in 1492 AD; 1666 AD was 7173/7174 from Adam). It also said the Pope was the predecessor of the Antichrist who would rule in Jerusalem – and very appropriately, Nikon called his new church grounds near Moscow “The New Jerusalem.”

The New Jerusalem Monastery's main Cathedral of the Resurrection. The New Jerusalem monastery near Moscow was founded by Patriarch Nikon and briefly served as his residence.

Fyodor AlekseyevIn 1654, a devastating plague epidemic struck Russia, killing up to 800,000 people. In the middle of it, the solar eclipse of August 1654 happened, further proving the “end of the world” as nigh. Finally, the Great Comet of 1680 appeared in the skies, as if quoting Revelation 9:1: “The fifth angel sounded his trumpet, and I saw a star that had fallen from the sky to the earth. The star was given the key to the shaft of the Abyss.” It stayed in the sky from November 1680 to February 1681. Can you even imagine how terrified the Old Believers (as well as all other Russians) were? Even Patriarch Nikon himself later recalled the solar eclipse amidst the plague struck him cold to the marrow. People were convinced that the world was ending. In 1666, the first self-immolation of the Old Believers happened in the Nizhny Novgorod region. And there were dozens more to come.

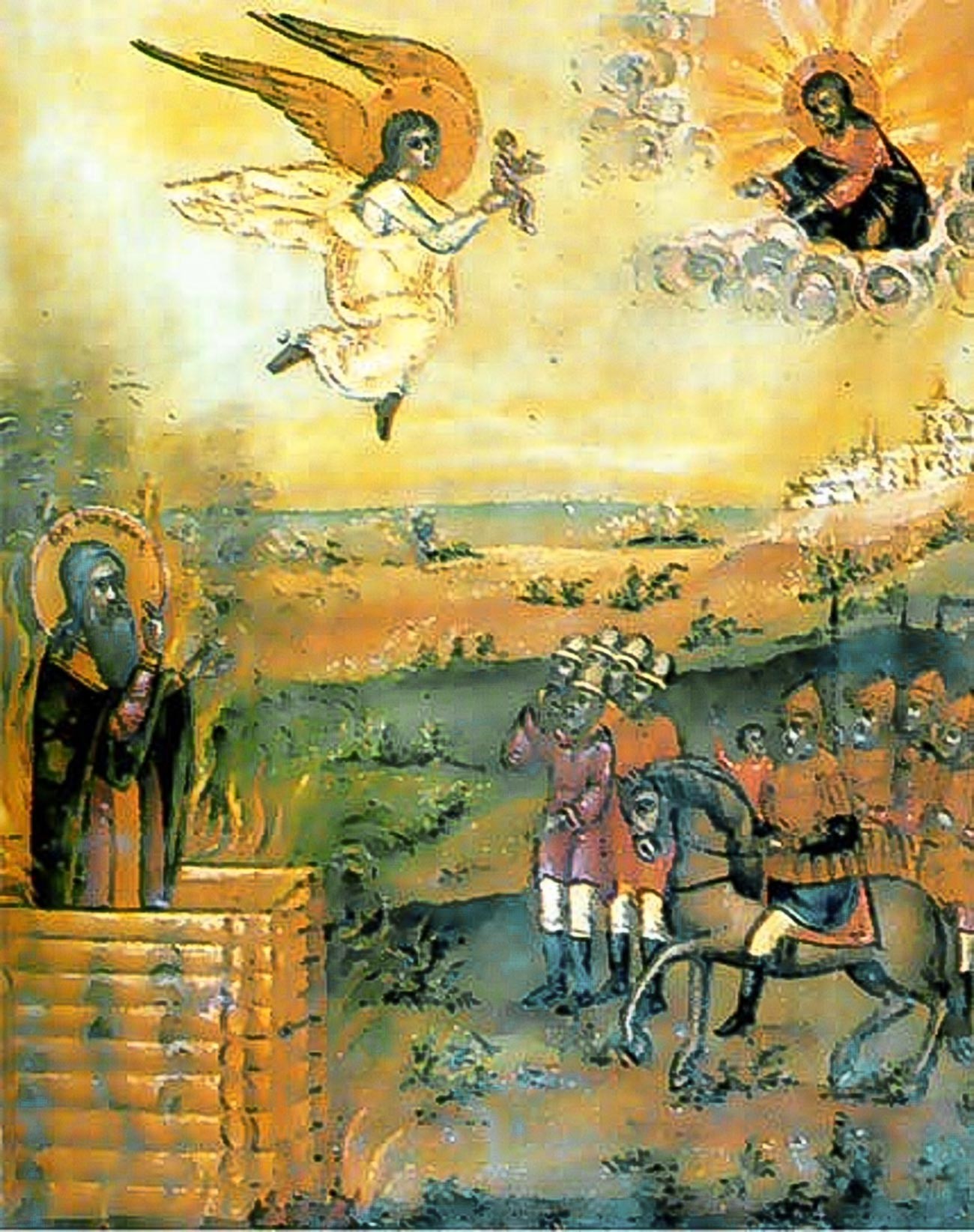

'Bishop Paul of Kolomna being burned,' a 19th-century Old Ritualists' picture. Paul of Kolomna (Павел Коломенский) was a 17th-century Russian prelate and martyr in the view of the Old Believers.

Public domainMarch 1666, Vologda region: 17 people self-immolated. 1672, Nizhny Novgorod – 2,000 people. 1675, Vologda region – another 2,000. In 1678, the Paleostrov self-immolation, one of the largest, took over 2,700 people at the sight of soldiers and officials who were sent to stop the burnings. In total in Russian history, there were over 100 officially registered self-immolations of the Old Believers.

Moreover, in 1685 the Moscow government led by Sophia Alekseyevna of Russia (1657-1704) introduced execution by burning for those Old Believers who refused to surrender their beliefs. Earlier in 1682, Avvakum Petrov (1620-1682), the leader of the Russian Old Believers and their revered saint, was burned alive in a log cabin in Pustozersk, Arkhangelsk region, against his will. This law and this appalling deed only whipped up the self-immolations that were already in full swing by the time.

The Old Believers considered this not to be a suicide – this was a martyr’s death as an act of protest against the anti-Christian civil powers and the corrupt church, as the Old Believers put it. They didn’t self-immolate ‘by themselves’ – the operation was mostly performed as a reaction to forcible conversion to the Russian Orthodox (now, Nikonian) faith, which the Old Believers considered unholy and lewd.

Avvakum Petrov on a 17th-century Old Ritualists' icon

State Historical MuseumThe self-immolation was thoroughly prepared – under the supervision of one of the Old Believer tutors (they didn’t have priests), a “burn house” was built – a vast wooden structure that would contain the self-immolators. For example, a ‘burn house’ built in the Arkhangelsk region for the 1685 self-immolation contained 230 bodies. It wasn’t usually a single-room house, more like several wooden cabins joined together, often in two or more storeys. Typical ‘burn houses’ were meant for several dozen people.

The house was then filled with hay, candle tow, and other flammable materials, including often a barrel or two of gunpowder. The windows and the door were ready to be sealed from the outside by other Old Believers who were to aide the self-immolators. As soon as the Old Believers learned about any military formation heading their way, they locked themselves inside the building and waited for the soldiers to come, then self-immolated.

Before self-immolation, all Old Believers and their children were symbolically christened again, because they were to face ‘baptism with fire’. Many of them took monastic vows. But not all of them were so brave to withstand the fire. Inside the ‘burn house’, certain trusted people (that were to burn with the others, too) were armed with rifles and axes to murder those who tried to escape – one should accept the ‘fire baptism’ with humility, because it was a door to eternal life in the Kingdom of God, the Old Believers preached. Anyway, death for those poor Old Believers came pretty soon, not from burns, but carbon monoxide poisoning.

Death of Avvakum, a 19th-century Old Ritualists' icon

Public domainOften, as the self-immolation started, a tutor would ascend the roof of the building and read a sermon before crashing down into the fire to die; written sermons were also often thrown out of the burning house. For Old Believers, who were banned and anathematized, this was the only way of communicating with the authorities.

Most self-immolations couldn’t be stopped even by soldiers. They continued in the 18th century and didn’t stop even after the persecution of Old Believers was banned by Catherine the Great in 1762. Between 1762-1825, 23 self-immolations were registered. One of the very last of them happened as late as 1941 in the Tuva region, where local Old Believers took WWII for another end of the world.

This article is written with a deep respect for the moral code and the history of Russian Old Ritualists and is meant for informational purposes only. The Old Believers are properly called the Old Ritualists, but are better known in English, and recognized by English language search engines, by that name.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox