“It was impossible to count the money, we estimated it by eye, by the roomful,” Sergei Mavrodi, the founder of MMM, recalled in 1994, talking of the scale of his company’s operations. The Ponzi scheme operated for just a few years, but in that time, it acquired 15 million investors across the country. MMM shares and coupons were circulated as a parallel currency to the ruble and foreign currencies; they were exchanged for food and clothes. And even after the courts declared him to be a fraudster, investors were ready to install him in the Kremlin. In fact, he was even elected a deputy of parliament while he was in prison.

In Soviet times, Sergei Mavrodi was a “dark horse”. Few people knew who he was or where he had come from. Prior to setting up his Ponzi scheme, Mavrodi, a software engineer by training, used to sell pirated audio cassettes, imported office equipment (he allegedly imported the first personal computers into the USSR), collected butterflies and bred aquarium fish. “A little Soviet man at the very bottom of the social ladder with his odd jobs, but one who possessed bold dreams and had illegal alternative occupations that allowed him to live better than most of his fellow citizens,” is how Forbes once described him.

In his baggy tracksuit bottoms, horn-rimmed spectacles and scruffy polo shirt, Mavrodi looked more like a school PE teacher who had come out of his apartment to take the trash out than a financial bigwig. On the other hand, this could have been his ‘key’ to success in getting people to open their wallets.

The ‘MMM Cooperative’, which later became a giant Ponzi scheme, was set up in Moscow in 1989. The name of the company was taken from the first letters of the three founders’ surnames - Sergei Mavrodi, his brother Vyacheslav Mavrody and Olga Melnikova (his brother’s first wife). However, Vyacheslav and Olga were only nominal figures, needed for registering the company, Sergey claimed.

Initially the ‘MMM Cooperative’ had nothing to do with finance, but it quickly became popular: Imported tech equipment sold like hot cakes at the time. The business was doing so well that in 1991, as part of a PR campaign, Mavrodi offered Muscovites free one-day metro travel, and two years later he made a New Year’s Eve TV address to the people of Russia, something that is usually done by the country’s president.

So, when Mavrodi issued JSC (Joint-stock company) MMM shares for sale for the first time, on February 1, 1994, people knew him well (or at least they thought they did). One share cost 1,000 rubles (equal to around $0.65 then). Share buy and sell prices were steadily increased according to the principle “today is always more expensive than yesterday”. Mavrodi personally set the quoted prices, which were actually arbitrary figures that didn’t correlate to anything.

For a very short time it worked. “There are no problems at MMM” was his advertising slogan. The company promised shareholders it would buy back their shares immediately upon request. Payments to participants in the Ponzi scheme were made using the money of new investors. By July 1994, the share price had reached 125,000 rubles ($81). “Mavrodi gave people hope - he was like a ray of light to them. All that time, we had lived in poverty and suddenly an opportunity beckoned,” explained actor Lyonya Golubkov [real name Vladimir Permyakov], who was the face of the MMM advertising campaign.

Friction with the authorities also quickly developed. Mavrodi claimed that his company accounted for almost a third of the national budget. He justified his actions, not in terms of a desire to enrich himself, but a desire to “intervene in what is the plunder of the country”. He said he wanted to use the money collected from the population to redeem state property put up for sale, so that it ended up in the hands of the people and not the oligarchs. “People become economic slaves to the oligarchs and then they are dumped on the rubbish heap with a pension of $100,” he used to say.

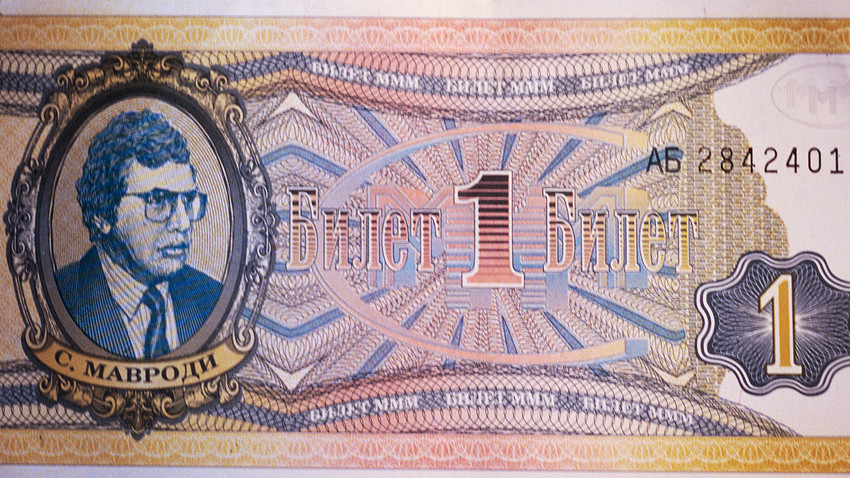

When the MMM shares sold out, the company asked for an additional issue, but the Ministry of Finance refused. Then, Mavrodi issued “MMM coupons” that looked similar to Russian 10 Ruble banknotes, but, instead of a portrait of Lenin, they had a portrait of Mavrodi.

The MMM coupon was not a security - in fact, it was just a piece of paper, the value of which rested on nothing more than Mavrodi’s promise that it was worth something. It was all a great illusion.

Mavrodi couldn’t be brought to justice immediately. The first accusations were made in August 1994. And he was accused not of fraud, but of tax evasion. “What taxes? If the authorities claim it is a pyramid scheme, does it mean then that I didn’t give them their share? Are they out of their minds?” the MMM founder sneered later.

He was arrested but, while in custody and under investigation, Mavrodi managed to register as a candidate for deputy of the lower house of parliament and to get successfully elected: Investors in the Ponzi scheme wanted to get their money back and actively voted for him. So he got parliamentary immunity and went into parliament straight from his prison cell. But Mavrodi didn’t turn up for parliamentary sessions and a year later was stripped of his mandate. He then disappeared. The investigation into MMM resumed and Mavrodi was put on the international wanted list.

He was detained in January 2003, in a rented apartment in Moscow where he had been hiding. Throughout this time, his security detail had brought him food and clothes, while he himself, using a false name, was registering ‘Stock Generation’, a virtual stock exchange, in a Carribean country.

Mavrodi was sentenced to four years and six months, but he was almost immediately released, because by that time, he had already served this term while in pre-trial custody (two years later, swindler Bernie Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison for organizing a similar Ponzi scheme in the U.S.).

The investors’ money was never found. Most likely, Mavrodi took it out through his offshore subsidiaries. After the trial, he continued to be involved in financial pyramid schemes, focusing on exporting them abroad: He opened similar schemes in South Africa and Latin America. In early 2017, the website of the local MMM scheme in Nigeria became more popular than Facebook. In 2011, he wrote to Julian Assange with a proposal to join forces “in the fight against the hypocritical global financial clique”.

More than 50 people died under MMM’s financial wreckage - they took their own lives when they realized that they would get nothing back. But Mavrodi was unperturbed. “I was told ‘they were deceived and didn’t know what they were doing’. But they were grown-up and mentally fit people.” was his response.

“The Great Combinator [a fictional conman in Soviet authors Ilya Ilf and Yevgeni Petrov’s novels] of the 1990s” died in March 2018 from a heart attack at the age of 62. “Did you know that no-one [among his relatives] wanted to take his body after his death?” one of Mavrodi's former employees said. His own brother refused to bury Mavrodi next to their parents. In the end, it was former MMM investors who decided to pay for his funeral.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox