A still from "The Mongol," 2007

Sergey Bodrov Sn./STV production, 2007Knyaz’ Yaroslav II of Vladimir was poisoned by Güyük Khan’s wife. At the age of 67, Knyaz’ Mikhail of Chernigov was executed in the capital of the Golden Horde (Mongol khaganate) for refusing to worship Mongol idols. Knyaz’ Mikhail of Tver had his heart ripped out in the same capital, the chronicle says. The Russian population was forced to pay substantial tributes, and Russian princes were only allowed to rule their duchies by the permission of the Khan of the Golden Horde. That’s how it was under the Mongol rule, or, as we call it in Russia, the Tatar-Mongol Igo (Yoke).

Prince Alexander Nevsky begging Batu Khan for mercy for Russia, End of the 19th century. Found in the collection of Russian State Library, Moscow

Getty ImagesIt’s hard to believe that events such as these were instrumental in the formation of the Russian state. But it was opposition to these actions that united the Russian princes – unfortunately, not with friendship, but under the iron fist of the strongest of them. “Moscow owes its greatness to the Khans,” wrote the great Russian historian Nikolay Karamzin (1766-1826).

At the time of the Mongol invasion of Rus’, the Mongols were advanced both in the military and in the systems of governance. Only unity could help the Russians to overthrow Mongol rule. How did it begin in the first place?

Genghis Khan

Public domainIt all started when Genghis Khan (1155-1227), the founder of the Mongol Empire, sent his son Jochi (1182-1227) to conquer the lands of what is now Siberia, Central Russia, and Eastern Europe. Giant armies of Mongol warriors (clearly over 100,000, an enormous number in the 13th century) easily defeated the weak and ill-numbered forces of the Russian princes, who were at war with each other before the invasion.

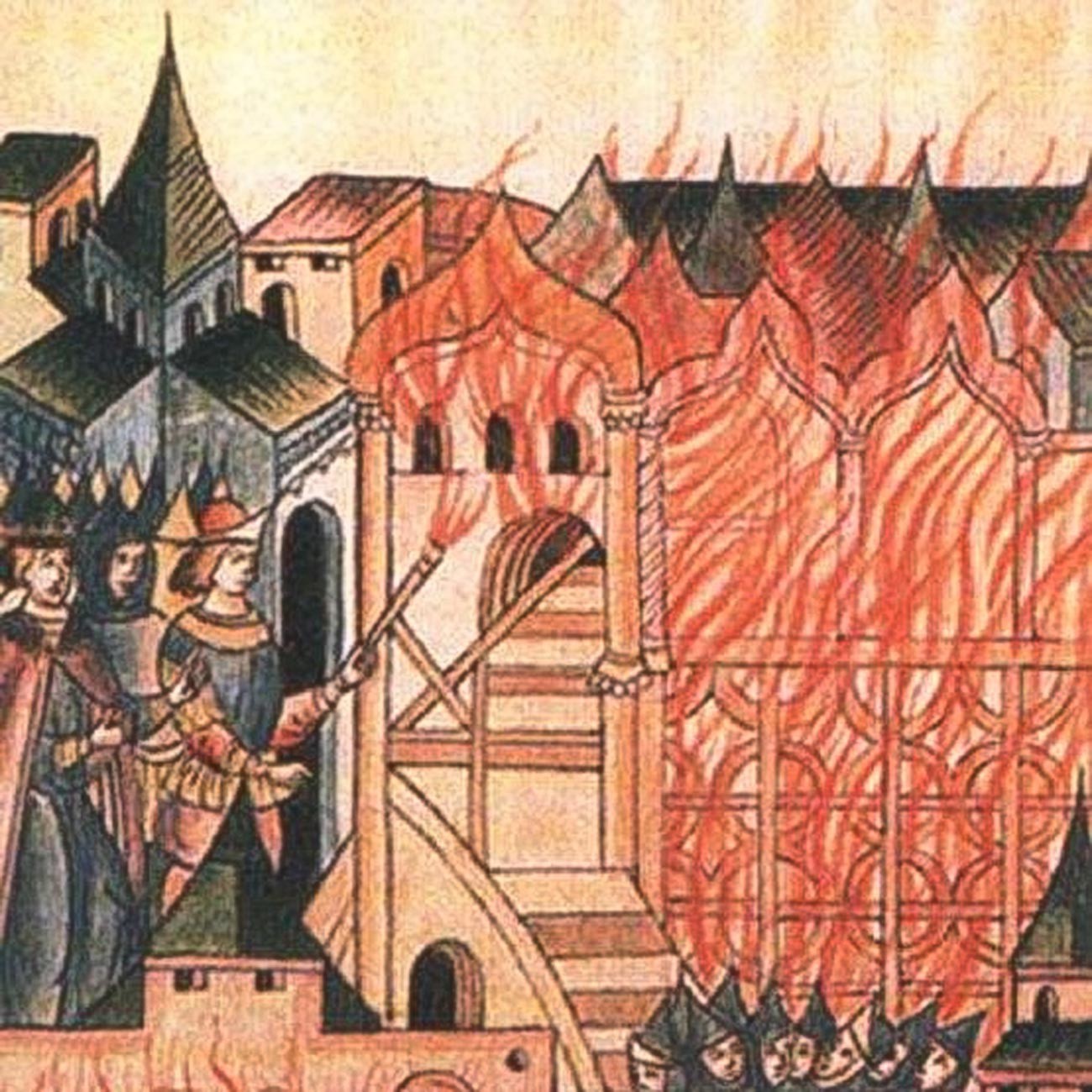

In 1237, the Mongols, led by Batu Khan, invaded Rus’. They took, ravaged and burned Ryazan’, Kolomna, Moscow, Vladimir, Tver – all the main Russian cities. The invasion continued until 1242 and was a terrible blow for the Russian lands – it took almost 100 years to fully recover from the damage the Mongol army did. Also, the lands and cities of the South – Kiev, Chernigov, Halych were burned to the ground. The North-Eastern lands, most notably Tver, Moscow, Vladimir, and Suzdal became the main cities after the invasion.

However, the Mongols didn’t want to conquer the land fully – they just wanted stable tributes. And they knew how to get what they wanted.

Batu Khan as seen on a Middle Ages Chinese etching

Public domainIn 1243, Yaroslav II of Vladimir (1191-1246) was the first Russian prince to receive permission to rule – he was summoned to Batu Khan, swore his allegiance to him and was named the “biggest knyaz’ of all Russians.”

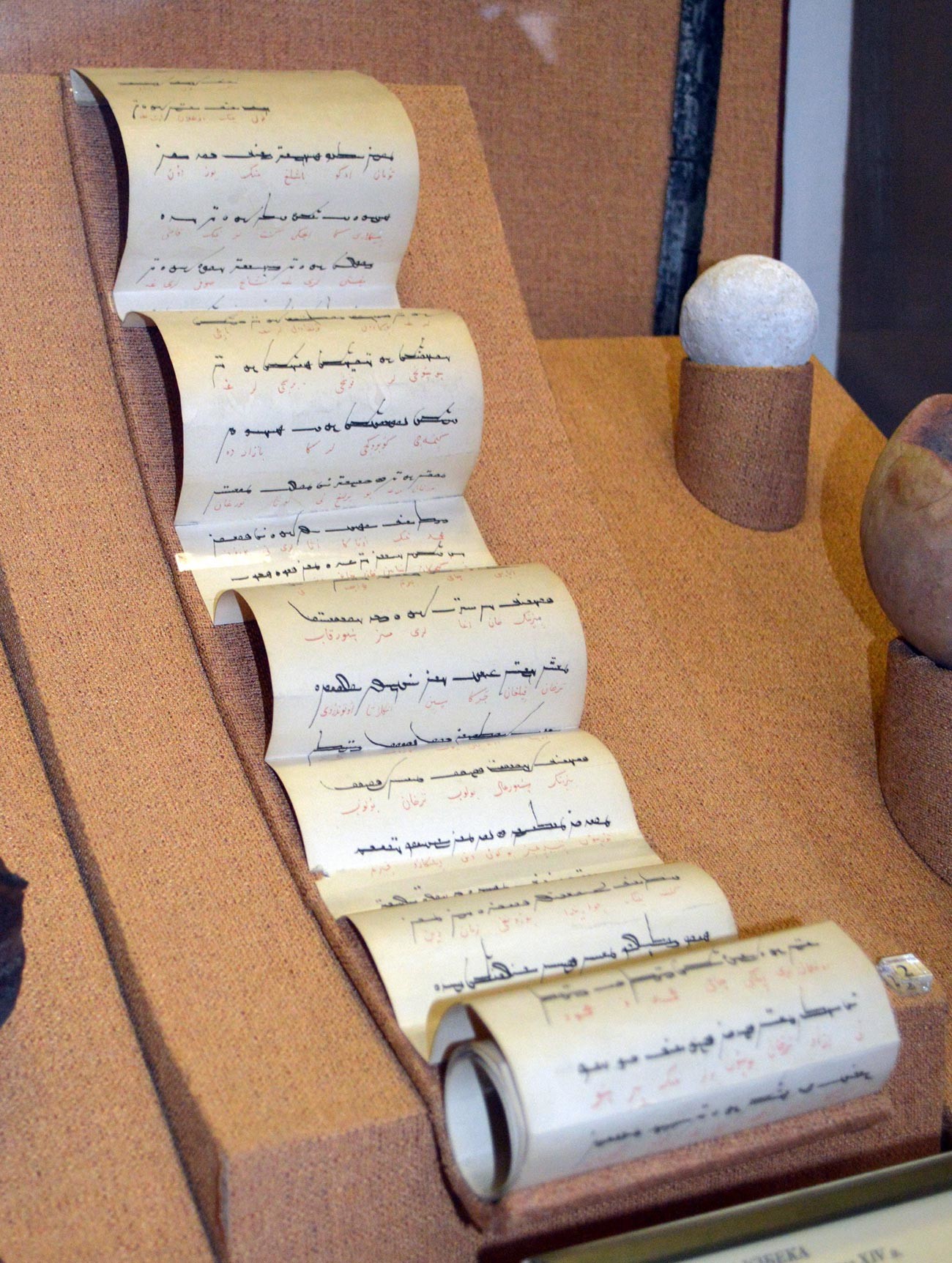

The ceremony of swearing allegiance to Mongols was very similar to the French ceremony of homage, where the liege kneeled on one knee at the feet of his seated sovereign. But in the Horde’s capital Saray, Russian princes were sometimes forced to walk on their knees to the Khan’s throne and overall treated like inferiors. It was this same Yaroslav II, by the way, who received the first jarlik and later was poisoned.

Jarlik (a shout-out, an announcement in the ancient Mongol language) was how Mongols called diplomatic credentials – protective charters they wrote and handed over to the Russian princes and priests. The important part of the Mongols’ policy was that they protected the Russian Orthodox churches, never ravaged them, and kept the clergy safe. For protection, the church was obliged to preach allegiance to the Mongol Tatars to their parishioners.

A typical Mongol jarlik dating back to 1397

Лапоть (CC0 1.0)The tributes were controlled and collected at first by the baskaks, the Mongol taxmen, who lived in Russian cities with their suite and security guards. To collect the tributes, the Mongols performed a census of the population of the subdued duchies. The tributes went to the Mongol Empire, and after 1266, when the Tatar-Mongol state of Golden Horde divided itself from the Mongols, tributes went to the Golden Horde’s capital Saray. Later, after multiple local revolts and following the Russian princes’ pleas, the tribute collection was handed over to the princes themselves. Otherwise, the Russians were left to live their life.

"The Baskaks"

Sergey IvanovThere was never any constant military presence of the Mongols, but if the Russians revolted against their rule, they could send armies. However, the cunning and politically sophisticated Mongol khans manipulated Russians, incited hatred and wars among them to better control the weak, divided states. Soon, the princes learned this tactic and started applying it against the Mongols.

For a century, there were innumerable military campaigns between Mongols and Russians. In 1328, Tver duchy revolted against the Mongols, killing the Uzbek Khan’s cousin. Tver was burned and destroyed by the Horde, and Moscow and Suzdal princes helped the Mongols. Why? How could they?

In a war between the duchies, the Moscow princes understood that somebody has to take the lead against the Mongols by subduing others to his rule. After Tver’s demise, Ivan I “Kalita” of Moscow became the first prince to collect the tributes from the Russian lands instead of the baskaks – that’s what he got for helping the Mongols to murder his compatriots – and at the same time, his enemies. However, this helped bring the famous “40-year peace” when Mongols didn’t attack the lands of Moscow (but ravaged other duchies). Meanwhile, Moscow used the defeats of other princes for their own means.

The sacking of Suzdal by Batu Khan in February 1238. Mongol Invasion of Russia. A miniature from the sixteenth-century chronicle

Public domainREAD MORE:Lessons in warfare Russians learned from the Golden Horde

Russians also quickly learned from the Mongols to use written contracts, sign acts, enact laws; Russians used the system of yams – road stations, employed first by Genghis Khan for multiple purposes: shelter for travelers, places to hold spare horses for army messengers, and so on. This system was installed in the Russian lands by the Mongols for their purposes but eventually started being used by Russians for their own good – to connect their lands.

The Tver uprising of 1328 as seen in a Russian chronicle of the 16th century

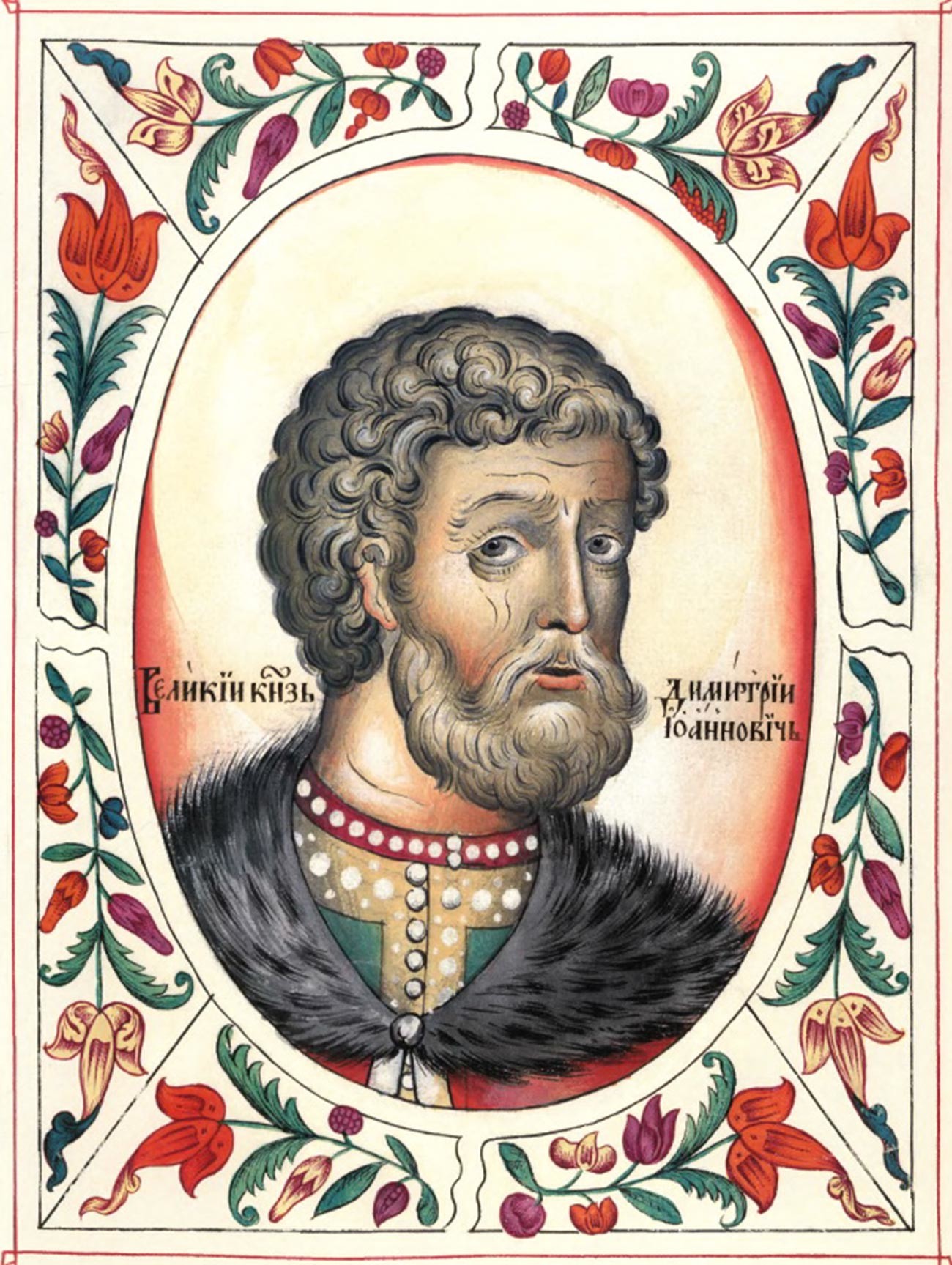

Public domainWhat Moscow princes learned from the ruthless Mongols was that you either kill your enemy or disable him so he can’t take revenge. Simultaneously with the strengthening of Moscow princes, the Golden Horde fell into a political crisis. In 1378, Dmitry of Moscow, known as Donskoy (1350-1389) for the first time in a long while, crushed one of the Horde’s armies.

In 1380, Dmitry Donskoy, who had earlier stopped paying tributes to the Horde, defeated the 60,000-110,000-strong army of Khan Mamay in the Battle of Kulikovo, a great moment of high spirits for all the Russian lands. However, in 1382, Moscow was burned by Tokhtamysh, a Khan of another part of the dismantled Horde.

For the next hundred years or so, Russian lands on and off paid tributes to different Khans of the Horde, but in 1472, Ivan the Great of Moscow (1440-1505) refused again to pay tributes to the Tatar Mongols. This time, the Great Duchy of Moscow was really great. Ivan and his father Vasily II the Blind had collected lands and princes and subdued them to Moscow.

READ MORE: How a 15th-century strange battle put Russia on the map

Ahmed bin Küchük, Khan of the Golden Horde, tried to wage war against Ivan, but after the famous standoff at the Ugra river in 1480, he returned home. This battle marked the end of the Mongol rule and control – but not the tributes. Russia continued sending money and valuable goods to different parts of the Horde just to make peace with militant Tatars. This was called “pominki” (appr. ‘memorables’) in Russian.

Dmitry Donskoy, an image from a Russian chronicle

Public domainRussia paid pominki to different former Horde dynasties until 1685. Formally, the tributes were banned by Peter the Great only in 1700, according to the Treaty of Constantinople between the Russian Tsardom and the Ottoman Empire. The Khan of Crimea, one of the last of the Khans at the time, and the Ottoman Empire’s vassal, was also the last to whom Russia paid. The treaty said:

“...Because the State of Moscow is autonomous and free – the tribute that annually was given to the Crimean Khans until now, henceforward shall not be given from His Holy Greatness of the Tsar of Moscow, nor from his descendants…”

It is very symbolic that Peter, the last great tsar of Moscow and the future first Emperor of Russia, signed this treaty in 1700, the first year that began in Russia not from the 1st of September, like in ancient Russia, but from January 1st – just like in Europe.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox