The short answer is - there were, of course, homeless people in Russia. However, the government persisted in making their existence out to be a myth. But how did you hide dozens or hundreds of people roaming the streets in search of food and shelter? Well, you didn’t - you simply gave it a different name.

In the early days after the Revolution, the prevailing view was that the homeless and poor would in time disappear as a sad remnant of the old regime - as soon as the Soviets were done building a welfare state. The Bolsheviks even kept statistics of the issue. The 1926 census counted some 133,000 individuals begging in the streets. The beggars turned out to almost always be homeless.

Registration of homeless children in 1928.

Sputnik“This fact is noteworthy, because we can see that the problem was being given attention, it was studied. Brilliant pieces of research then came out about poverty - the motives, the causes and the content of this social category,” says Elena Zubkova, senior researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Russian History.

The new rule then took steps to combat that poverty: it began with small pension schemes for select categories of people (so insignificant they didn’t even touch the survival minimum) and employment assistance. Meanwhile, entire strata of Russian society, such as the formerly privileged, were simply refused help.

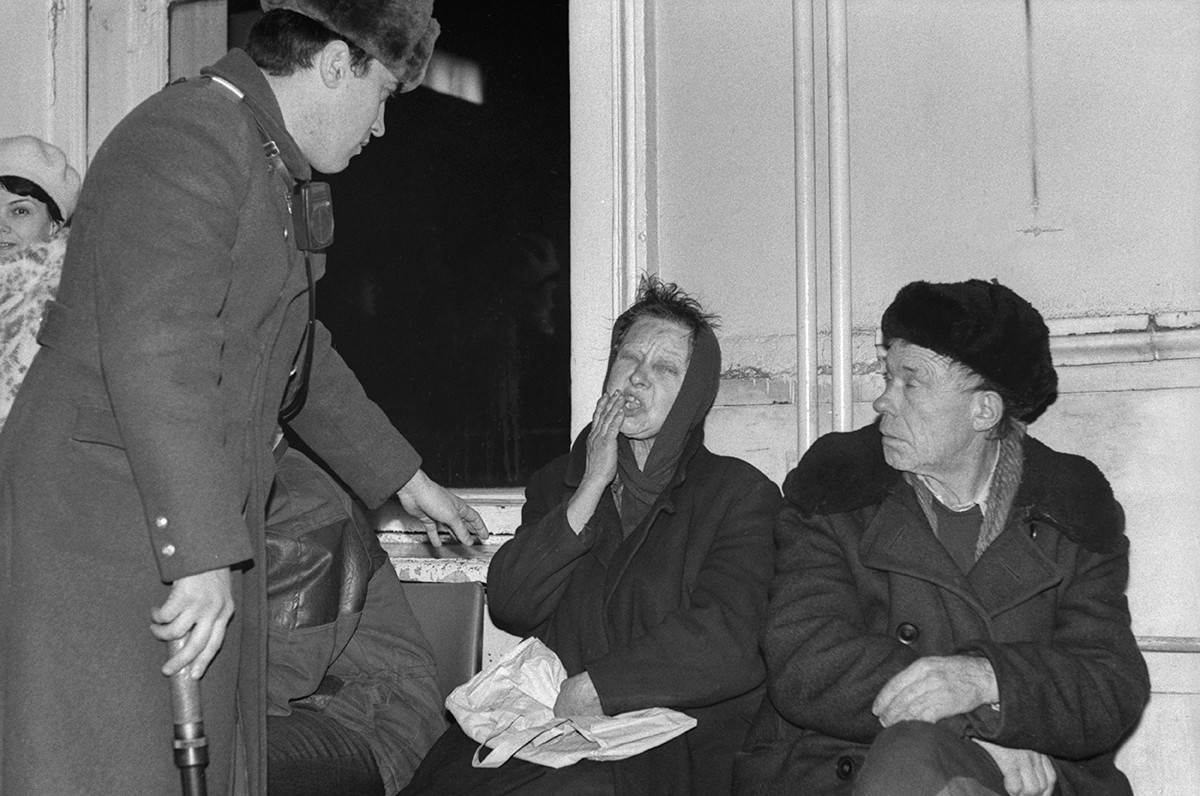

Homeless Muscovites in 1991.

Alexander Sentsov/TASSHowever, it soon became obvious that the fight against poverty isn’t going as swiftly or effectively as was hoped. Years passed, as the state’s ideology machine continued to hammer in the belief that the country was on the very precipice of happiness for all. So, how did it deal with the problem again? It simply started referring to it as a “defect”!

In the 1930s, all research was abruptly stopped, with the issue then categorized as a personal one, stemming out of some very perverse choices - on par with alcoholism and prostitution. The USSR Constitution then appeared, containing the claim that the country was successful in establishing the foundation for a socialist society. Then, at the 8th All-Union Congress, Joseph Stalin declared that the root causes behind poverty and unemployment had been eliminated.

The fight against homelessness was then transformed into all-out repressions. The poor and the vagabonds were hunted and cast out of the big cities - a practice that had existed since tsarist days, which contained a ban on particular categories of citizens in St. Petersburg and Moscow. But it was the Bolsheviks that really took the idea of “expulsion from the flowering capital” to the next level. It was referred to as “eviction beyond the 101st kilometer”. The measure would often be practiced in the runup to major national events and celebrations e.g. Moscow’s 800th birthday, in 1947, or the Olympic Games in 1980.

The rest of the year, a different procedure was used. The police would pick the beggar off the street and begin to investigate whether they had any relatives, whether Moscow was their place of residence and so on. In the absence of any relatives, but in the presence of the ability to do physical labor, authorities transferred the individual to the body in charge of employment. The unemployable, meanwhile, were housed in homes for the disabled. Or so it went on paper.

The scheme absolutely did not work in reality. According to Zubkova, there were major issues with employment, coupled with a catastrophic shortage in disabled homes. They were instead sent to homes for the mentally disturbed. It wasn’t difficult to come up with the diagnosis. It was, however, nearly impossible to get out.

Then there was the matter of needing somewhere to hold all these people you were questioning. In 1946, the reception and distribution cells appeared, terribly unsanitary and with ungodly conditions. That program did not last long.

In 1951, the law “on measures in the fight against antisocial, parasitic elements” came out, stipulating that the homeless were to be sent to specially allocated areas of the Soviet Union for a period of five years. Exile, in other words. But it got worse in the 10 years that followed. The Soviets had started to criminally prosecute unemployment - what they called “parasitism”. And the measure didn’t just touch the homeless: ordinary people whose financial income was unofficial also fit the bill. And if you had no roof over your head, you were sent to prison for up to two years.

With such radical changes in place, homelessness had become virtually invisible to the public eye. You couldn’t see it in the metro or on the street. Starting from the 1960s, they had to hide in basements and attics, in abandoned bomb shelters and inside the nodes of heating mains, without hope of any assistance.

To give credit where it’s due, social policy governing the issue of homelessness had indeed progressed from the 1930s. Poverty, as a taboo topic, had received its own euphemism in the media - “subpar material welfare”, and that’s where the government got to work. For example, in the 1977 rewrite of the Constitution, the right of every Soviet citizen to a home was instilled. However, according to the same document, the rule was predicated on the development of the state and social housing fund. But that proved insufficient for providing 250 million Soviet people (290 million at the time of Soviet collapse) with roofs over their heads.

Things had gotten visibly worse toward the late 1980s, when a sharp food and basic necessity deficit in the country led to the creation of a card system. Stamps would be distributed to accommodation services and in order to gain access to one, you had to have a registered address. Those without could not make use of the stamp program. “If one could make an illegal living and earn enough to buy food, the stamp system put an end to that and led to the homeless simply dying,” recalls Valeriy Sokolov, formerly homeless and the founder of the ‘Nochlezhka’ organization for the homeless. He was left without a roof over his head at 22: He had spent several years in Ukraine and upon return to his hometown of St. Petersburg, discovered that his relatives wrote him out of the apartment’s tenant list.

Even toward the end of the Soviet Union, authorities were unwilling to reveal the official scope of homelessess. Anatoliy Sobchak, who became mayor of St. Petersburg in 1991, declared that there were no homeless in the city. Moscow mayor Yuriy Luzhkov frequently claimed the same thing. Meanwhile, the law against vagrancy disappeared from the criminal code the same year, with the collapse of the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox