‘Prince Serebrenni’ (‘Prince Silver’), written by Alexey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, is a novel about the times of Tsar Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584). It centers on the exploits and adventures of Nikita Serebrenni, a fictional Russian Prince surrounded by real characters of the era, including Tsar Ivan himself, his close-knit circle of oprichniks (a half-religious sect of warriors), and other notable figures.

Based on historical sources and literature, the novel is praised for its high historical accuracy and offers a dramatic glimpse into the epoch. Especially gripping is the image of Tsar Ivan, both cruel and pious.

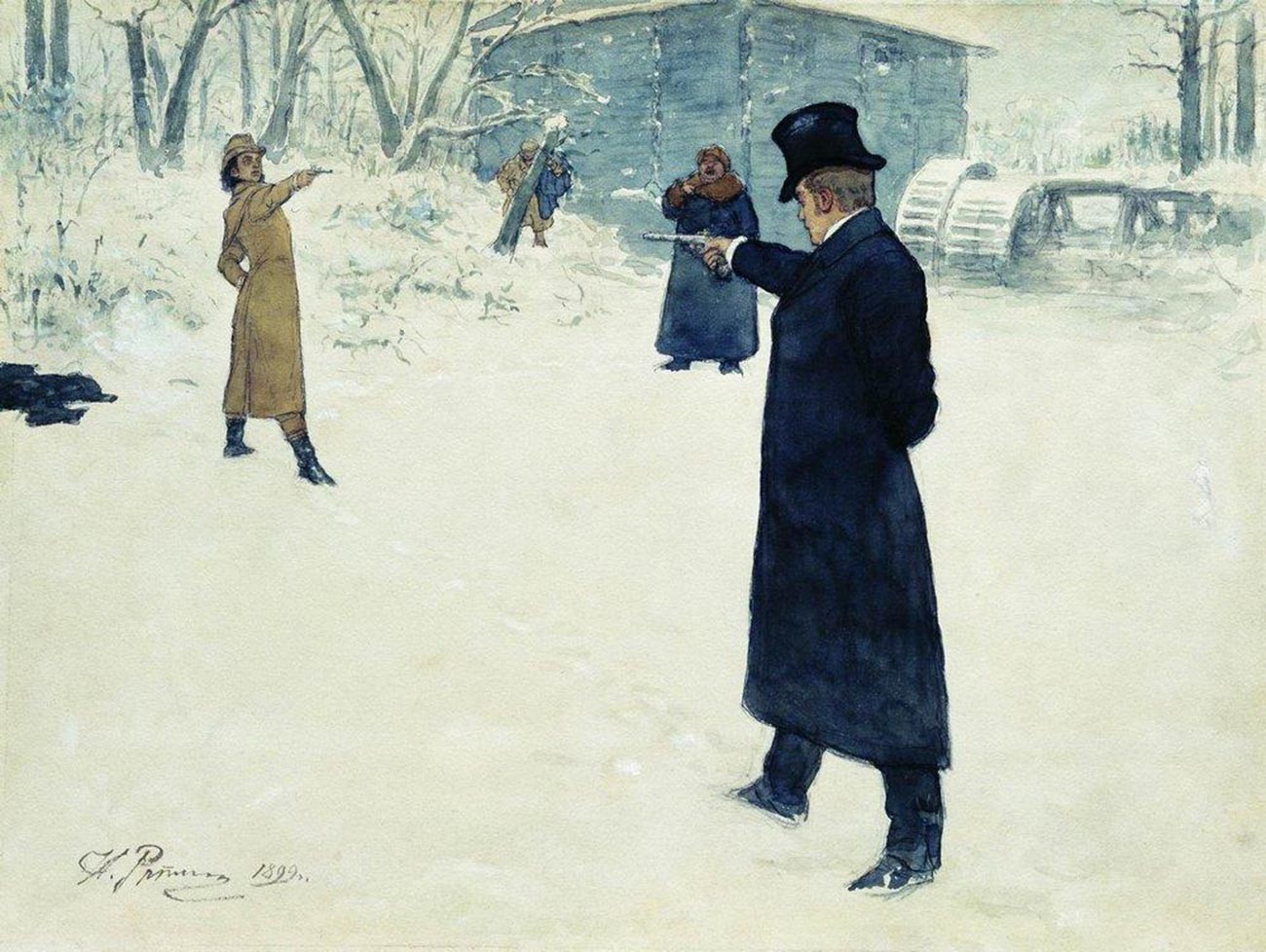

"Duel of Onegin and Lenskiy" by Ilya Repin

Ilya RepinThis novel in verse, written by Alexander Pushkin, is often called ‘the encyclopedia of Russian life’ for a reason. ‘Eugene Onegin,’ a 5,446 line masterpiece, contains an exhaustive description of the world of a Russian nobleman of the 1830s, with all his problems, worries and woes, from financial and civil matters, to love life and questions of honor and existential conflicts.

The novel centers on the life path of the eponymous character, who challenges his best friend to a duel, cynically defies society’s norms but eventually is stopped in his tracks by the backlash of his own attitude.

The whole novel is a complicated and beautifully crafted tale of a dandy’s downfall. Alexander Pushkin called it his foremost masterpiece.

READ MORE: Which character are you from 'Eugene Onegin'?

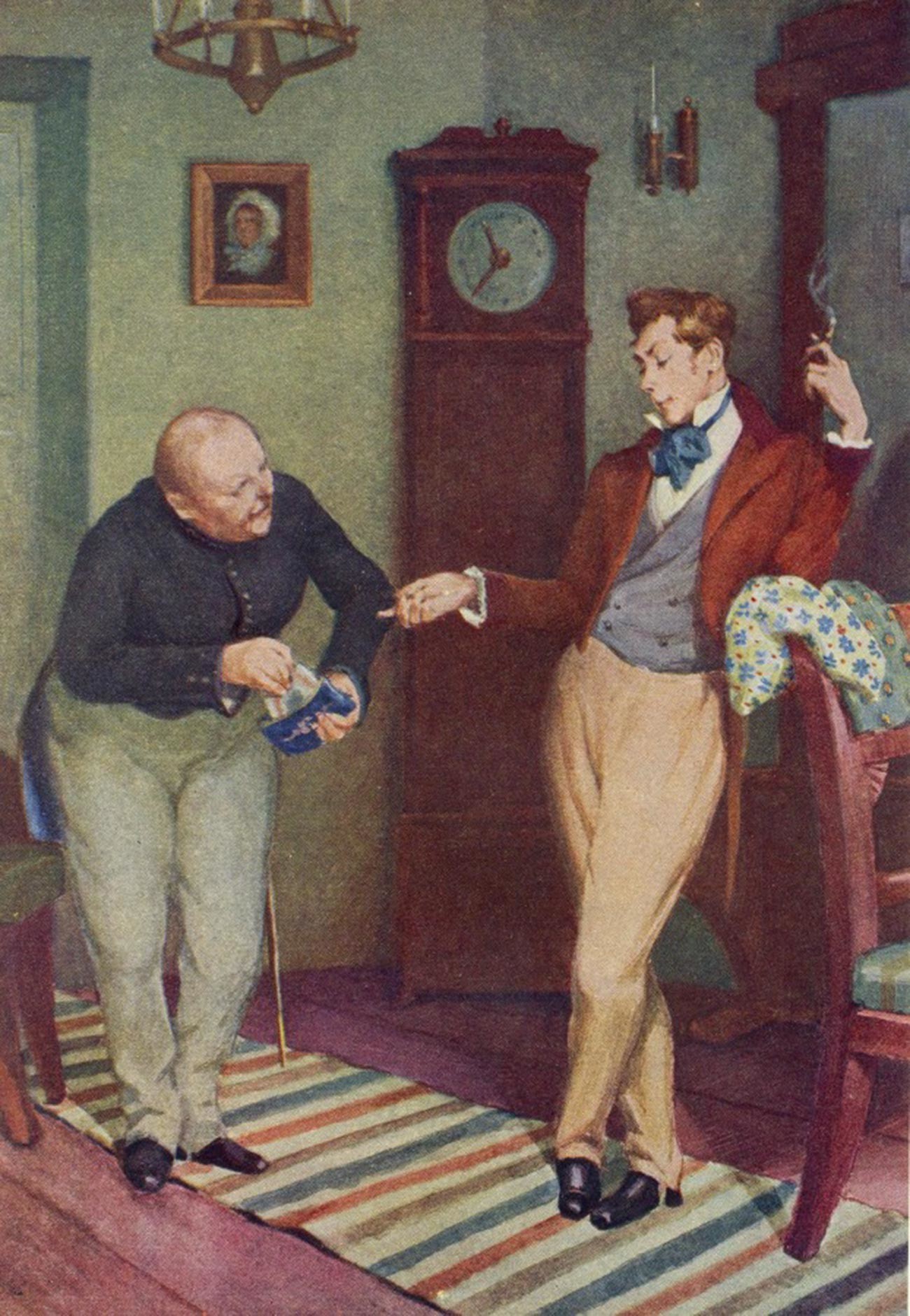

An illustration to "The Government Inspector" by L. Konstantinovsky

L. KonstantinovskyA comic play that is hilarious, tragic, and insightful at the same time, ‘Revizor’ centers on Khlestakov, a petty civil servant that decides to play a trick on the administration of a small provincial town in Russia: he poses as a government inspector, while in reality, he’s just a fraud passing through town.

Khlestakov witnesses all levels of bribery and plain flattery that local civil servants and members of society perform in order to comfort him, thinking he’s the one to define their future destiny. In a dance macabre of various disgusting and comical characters, the fascinating genius of Nikolay Gogol shows the reader all the uncanny sides of Russian provincial life of the 19th century.

After attending the premiere of the play, Emperor Nicholas I said: “What a show! Everybody had their share [of criticism], but me – most of all!”

‘The Government Inspector’ on Amazon

READ MORE: 5 must-read books by Nikolai Gogol to understand Russia

"Pechorin" by Mikhail Vrubel'

Mikhail Vrubel'“A Hero of Our Time, gentlemen, is, in fact, a portrait, but not of an individual; it is the aggregate of the vices of our whole generation in their fullest expression,” Mikhail Lermontov wrote in the foreword to ‘A Hero of Our Time.’

The novel centers on Pechorin, a character who contradicts, but complements the image of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin – he is, too, a dandy, but a dark, Byronic one, and the story of his life is tragic and twisted. The novel’s plot is non-linear, which adds to the dramatism.

Historically, the novel is a fascinating depiction of the life of the Russian officers in the Caucasus, and a compelling story about the Russian nobleman’s treatment of honor and relationships with women. It is written in a unique, timeless tone that resonates with the reader even to this day.

‘A Hero of Our Time’ on Amazon

READ MORE: A Virus of Our Time: A character from Russian literature is an example of the coronavirus spread

'The Siege of Sevastopol' by Franz Roubaud (1856-1928)

Franz RoubaudIn 1854-1855, Leo Tolstoy, an officer in the Russian Army, was present at the Siege of Sevastopol, which took place during the Eastern (Crimean) War. He survived numerous bombardments and participated in combat. Tolstoy’s first widely popular work, ‘Sevastopol Sketches’ are not fiction but rather the reports of a war correspondent – the first work of this kind in Russian history.

Written with attention to detail and without any fear or remorse, the three ‘Sketches’ capture exactly what it was like to be present during one of the most dramatic sieges in the history of the Russian army that was eventually lost. In the ‘Sketches,’ Tolstoy demonstrates the horror and awful waste of war.

‘Sevastopol Sketches’ on Amazon

READ MORE: Literary Crimea: In the footsteps of Russia’s most famous writers

Andrey Mironov as Ostap Bender

Mark Zakharov/TO 'Ekran", 1976A satirical (and really hilarious) novel, ‘The Twelve Chairs’ is set in the Soviet 1920s and follows the protagonist, con-man Ostap Bender on a quest to find a stash of jewelry hidden in one of

twelve chairs in a certain furniture set – but he doesn’t know for sure, which one!

Despite the fact that the novel is quite short, it manages to show the universe of the early Soviet reality with humor, wit and gripping detail. The characters go through adventures in a Russian provincial town, mingle with the crowd at a Moscow furniture auction, travel aboard a tourist ship and get to feast at the Russian-Georgian border…

The novel was and still is hugely popular among Russians for its energy and fast-flowing style of writing. The same characters continue their exploits in the sequel to the novel, “The Golden Calf” (1931)

READ MORE: Il'f and Petrov: The USSR’s most funny and daring writing duo

Convicts working in a labor commune of the People's Commissariat for the Internal Affairs in Moscow

МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruIn 1945, Alexander Solzhenitsyn was convicted on charges of anti-Soviet activity and spent almost eight years in prisons, labor camps, and other penal institutions. For a considerable part of his term, Solzhenitsyn, a mathematician, was imprisoned and worked among other scientists in several sharashkas – secret research laboratories within the Gulag labor camp system.

The harsh experiences Solzhenitsyn endured in these institutions became the basis of this largely autobiographical novel ‘In The First Circle.’ The very name implies that the author had seen only the first circle of the ‘Soviet hell’ the Gulag system was.

Solzhenitsyn wrote the novel without any hope for publication, so it is full of real-life details that do the Soviet oppression apparatus the justice it deserved. Most of the novel’s characters are modeled after other convicts Solzhenitsyn met in the Gulag system.

Copies of the novel, distributed through unofficial, illegal samizdat [self-published] channels, were hunted down and confiscated by the KGB. The novel was finally first published in full in 1968 by Harper & Row, New York.

‘In The First Circle’ on Amazon

READ MORE: Alexander Solzhenitsyn: 5 books by the Soviet dissident author that you should read right now

Varlam Shalamov did a much, much harsher labor camp time than Solzhenitsyn – he served two sentences, first in 1929-1931, and then in 1936-1951. Both of his terms were for anti-Soviet activity. From 1937 to 1945, Shalamov was imprisoned in the harshest conditions at the coal and gold mines in the arctic region of Kolyma.

The ‘Kolyma Tales,’ were partly published in 1966 and 1967 in the USA and Germany, and in full, in 1978 in London. During the author’s life, none of his Gulag prose was published in the USSR.

‘Kolyma Tales’ consists of six volumes of short stories, sometimes interconnected by the same characters. In part a documentary retelling of the reality Shalamov witnessed, they also rely on stories he heard.

Shalamov’s style, very frugal and precise, is somewhat similar to Chekhov’s. The factual matter of the stories is mostly brutal, sometimes horrific, full of monstrous events of cruelty and inhumanity people really suffered in the Gulag. It leaves the reader breathless, but Shalamov restrains himself from making judgements, leaving that to the reader.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that without reading ‘Kolyma Tales,’ one knows nothing about the real horror of the Gulag.

READ MORE: 7 quotes from Varlam Shalamov’s ‘Kolyma Tales’ that will give you chills

One of the few books about Soviet reality that became widely known and famous outside the USSR, ‘Moscow-Petushki’ was labeled by its author Venedikt Yerofeev a poem, although written in prose. It tells the story of an alcoholic intellectual who travels by a suburban train from Moscow to the suburban town of Petushki to visit his fiancee and child.

According to the novel’s plot, the protagonist is stinking drunk all of the time, but this is not jolly drinking and by no means a joy ride – ‘Moscow-Petushki’ is a tragic tale of the life of a destroyed person in the inhuman society of a failing Soviet state. It takes on all aspects of Soviet life with bitter humor, deadpan frankness, and the attitude of a snobbish, highly educated social outcast that Yerofeev himself was.

‘Moscow-Petushki’ is also considered by many as a textbook of Russian obscene language.

‘Moscow to the End of the Line’ on Amazon

READ MORE: 5 life lessons from Venedikt Yerofeyev, the Soviet author who celebrated alcoholism

A still from the "Generation «П»" movie, 2011

Viktor Ginzburg/Gorky Film Studio, 2011Viktor Pelevin, one of the most secretive and reclusive of modern Russian writers, probably wrote ‘Generation «П»’ during the 1990s. The novel is about Russian people born in the 1970s, who were grown-ups already when the USSR collapsed, and the first generation to face the new economic and political reality of the 1990s.

The protagonist, Babylen Tatarsky, an educated young man, graduate of the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute, becomes a copywriter, producing advertising slogans, and then, a senior ‘creator’ of TV-shows. Tatarsky understands that he is one of the manipulators that can feed TV audiences almost anything. Upon embracing his power, Tatarsky starts to look for the real meaning of life, only to realize everything is ruled by the dark Mesopotamian gods of the ancient past. ‘Aided’ on his quest by psychedelic drugs, Tatarsky tries to solve the riddles of intellectual consumerism.

‘Generation «П»’ is a bustling postmodern text that centers more on the plot and the subject than on the writing itself, and as such, is slightly different from a ‘usual’ Russian book. But, as literary critic Pavel Basinsky put it, the novel is very reliable and will be able, even in a hundred years’ time, to allow the reader to understand the life of Russians in the 1990s.

READ MORE: How Victor Pelevin creates myths for the new Russia

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox