A legend has it that Joseph Stalin personally approved Andrei Gromyko’s candidacy for the work in the Soviet foreign Ministry, because the sonorous surname had caught the dictator’s eye.

“Gromyko. A good surname!” Stalin supposedly said.

Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet ambassador to the United States, with his wife and children in their private apartment at the embassy in Washington, 1944.

Getty ImagesThis story may or may not be true, but the dictator of the Soviet Union did play a huge role in bringing Andrei Gromyko to his position in foreign affairs, albeit in a more indirect and also more sinister way.

In the 1930s, Stalin repressions exsanguinated the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs: Many trained diplomats were repressed and vacant offices had to be filled with new cadres. New candidates had to comply with two criteria: they must have had some knowledge of the English language and had a “proletarian” or “peasant” ancestry line.

As it happened, young Andrei Gromyko grew up in a peasant family and learned English from his father, who managed to go to Canada for a brief period to do timber cutting. Gromyko the candidate had a “noble” Soviet origin, knew English, was 6 feet 1 inch tall and had a sonorous name — all these factors made him an ideal candidate for a job in People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs.

“I became a diplomat by accident. The choice could have fallen on another guy from the workers and peasants,” Gromyko said years later.

Even if Stalin didn’t personally select Gromyko out of the list of other candidates, then he was instrumental for Gromyko’s rise in a different way.

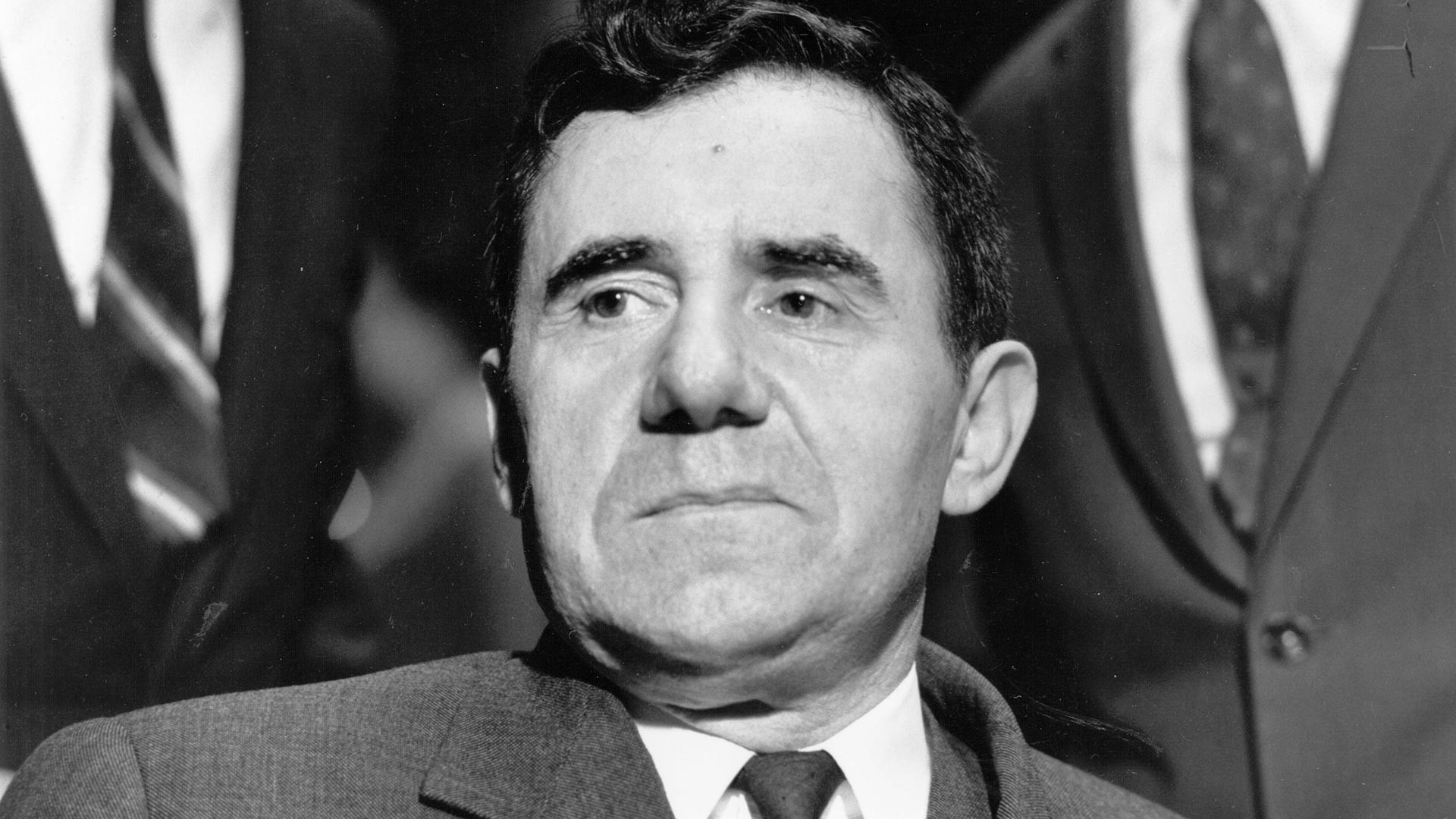

He was at times compared to a bulldog who wouldn’t let his victim go and to a heavy locomotive that slowly but surely goes in a given direction. And these were not just metaphors.

Andrei Gromyko, who became the Russian Ambassador to the UK in 1952, shakes hands with the Conservative Prime Minister, Winston Churchill outside 10 Downing Street.

Getty ImagesOne of Gromyko’s many talents was seemingly infinite patience. Some foreign diplomats involved in negotiations with the Soviet minister found it hard to go through long-distance negotiations with Gromyko when he did not feel any discomfort in arguing over the smallest details for hours.

Nonetheless, his personality charmed many of his colleagues. American diplomat Henry Kissinger said he appreciated Gromyko’s manners: “The impression that Andrei Gromyko made was of a very dour individual, very professional, very correct, and that is true. That’s what he was. But I would like to add to that: highly intelligent, always prepared, never lost his composure. He had a terrific sense of humor, which was not obvious right away, but once one got to know him, it was of extraordinary help in conducting our dialogue.”

He was often referred to by his counterparts as ‘Mr. No’. He used to reply that he “heard their ‘no’ much more often than they heard my ‘Nyet’”. Yet, it was not a secret between diplomats of the era that Gromyko often took an uncompromising stance on many foreign affairs matters that he was involved in.

As it turns out, a personal tragedy might have played a role in making him so iron-willed. During WWII, when Gromyko only began his work in foreign affairs, his three brothers were fighting in the trenches of the world war. Two of them were killed in the fighting and the other died of injuries after the war had ended.

The diplomat always remembered his family’s contribution to the victory when it came to negotiations that either involved Germany, the USSR’s former foe, or the post-war international order.

Gromyko once confessed the memory of his deceased siblings gave his negotiations a sense of fateful importance and personal investment.

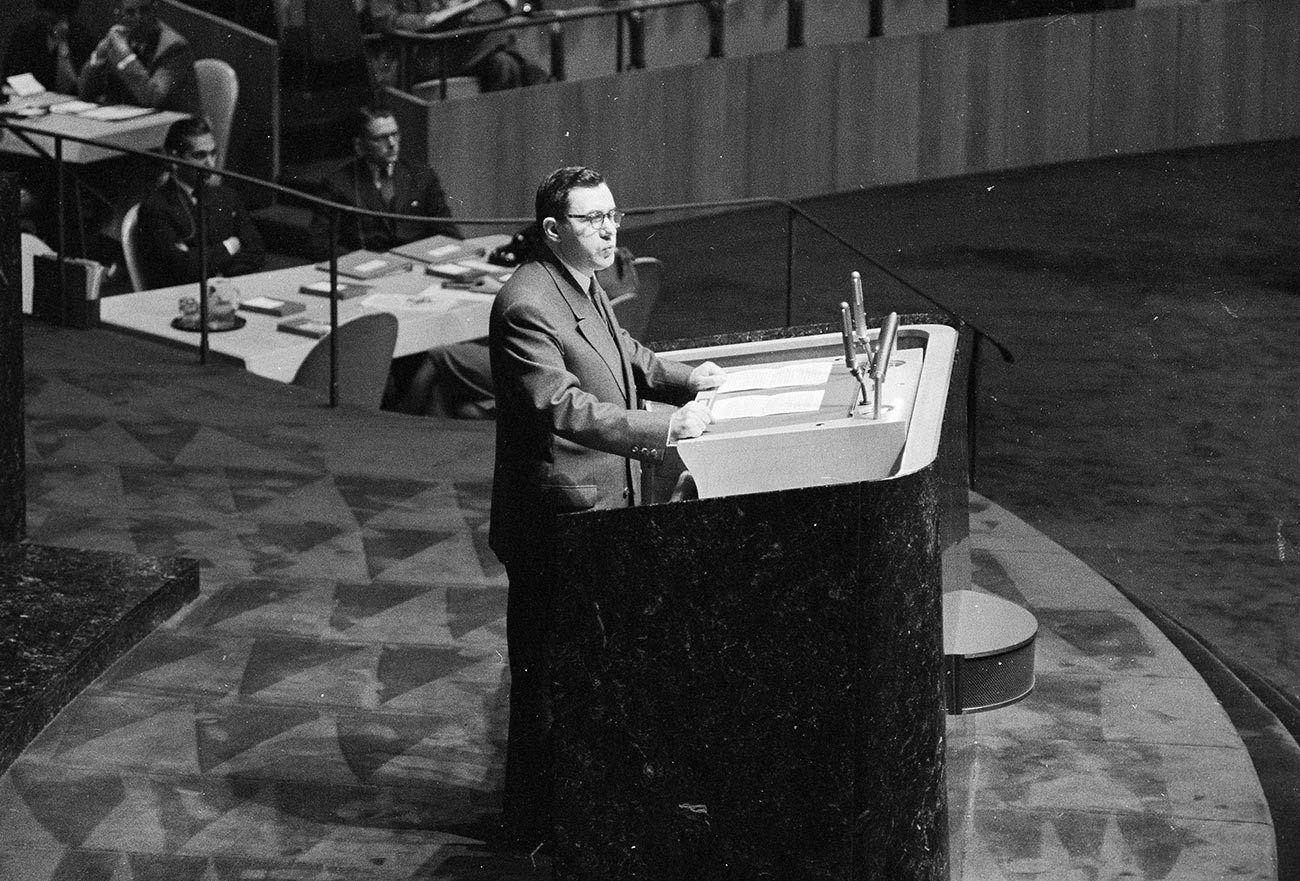

Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko addresses a meeting of the United Nations General Assembly.

Getty Images“We will not change the outcome of the war. If we give in to them we will be cursed by all those who were tortured and killed. When I negotiate with the Germans, I sometimes hear my brothers whisper behind my back: ‘Don’t give in to them, Andrei, don’t give in, it’s not yours, it’s ours!’” was how Gromyko explained his reasoning behind his uncompromising method of negotiations.

Andrei Gromyko was instrumental in shaping the post-war world and also in making it a safer place, to an extent it was possible to make it during the Cold War.

In his extensive diplomatic career — Gromyko spent 28 years as a foreign minister of the USSR and many more years in diplomatic service in other positions — Gromyko was a key player in virtually all the most important political events of the 20th century.

U.S. State Secretary Henry Kissinger (left) and the USSR's Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko (right).

Yuri Ivanov/SputnikHe helped prepare the Tehran Conference, where Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill met in 1943. He actively participated in the preparation of the Potsdam Conference, which in 1945 was where the ‘Big Three’ shaped the post-war global order.

He signed the founding charter of the United Nations on behalf of the Soviet Union, becoming a signatory of the charter that established the organization that would become a symbol of the globalized world in the years to come.

John Kennedy and Andrei Gromyko in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington D.C.

Cecil W. StoughtonFinally, the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty — a document that banned nuclear weapon tests in the atmosphere, in outer space and underwater — was also signed in 1963 partially thanks to Gromyko’s efforts, which helped make the world a little safer.

Yet, Gromyko especially valued one of his contributions to the world over others: “I consider the greatest personal success to be the consolidation of post-war borders in Europe by a treaty. If European countries refuse these agreements and start violating them, well… war will come to Europe again.”

In 1985, Gromyko could have become the de facto leader of the Soviet Union, as he was a probable candidate for the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, the highest post in the Soviet Union.

Despite Gromyko’s apparent ambition to leave diplomacy and compete for the highest office in the USSR, he backtracked on the plan at a key moment. After the death of Soviet leader Konstantin Chernenko in 1985, Andrei Gromyko pathed the way to the top for Mikhail Gorbachev, instead.

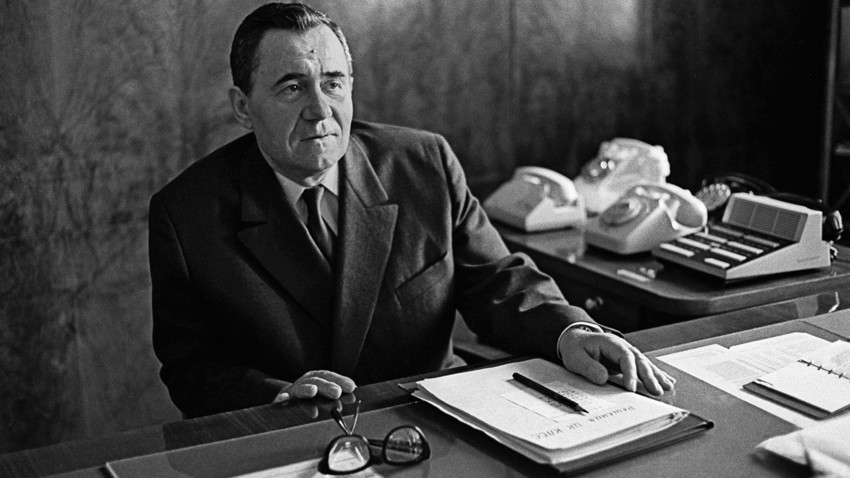

Andrei Gromyko

Getty ImagesThe reasons behind Gromyko’s decision to withdraw his candidacy are unclear, especially considering his somewhat skeptical regard for Gorbachev and, later, his policies. However, Gromyko was the one member of the politburo who endorsed Gorbachev’s candidacy at the expense of other potential candidates for the highest office in the Soviet Union.

As time passed, Gromyko was apparently disappointed in his former choice and questioned Gorbachev’s methods of running the country. However, there was little Gromyko could do about it, as he has been moved to a mostly ceremonial office of the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, also known as the President of the USSR (contrary to the U.S. system, the president did not have the same power as did the General Secretary in the USSR).

Mikhail Gorbachev and Andrei Gromyko during a Soviet Central Committee plenum in 1987.

Getty Images“I cannot say that Gorbachev treated Gromyko with excessive gratitude. Gromyko had helped appoint him as General Secretary. But he was removed as foreign minister, and he became president of the Soviet Union. President of the Soviet Union was not an extremely time-consuming job, so when I came to Moscow as a private citizen, I would frequently call on him at his office in the Kremlin, and we reminisced like veterans from the Thirty Years’ War who meet again after many battles,” said renowned U.S. diplomat Henry Kissinger about his opponent, colleague and friend.

He resigned from politics on October 1, 1988. As of today, Gromyko remains one of the most respected diplomats in the world and also the longest serving foreign minister in the history of the Soviet Union and modern Russia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox