The White Army's "General Drozdovsky" and its crew.

Public DomainIn the summer of 1919, at the height of the Civil War, the young Russian Soviet Republic was surrounded by enemies. In the northwest, Petrograd (as St. Petersburg was then called) was threatened by General Nikolai Yudenich; in the west Bolsheviks were fighting with Polish forces, while in the east they struggled with the troops of Alexander Kolchak who had been recognized by the Whites (counterrevolutionary forces) as the Supreme Ruler of Russia. In the south, the Red Army was opposed by the Armed Forces of the South of Russia (AFSR) under the command of Anton Denikin, who decided to end Bolshevism with one decisive blow, namely the capture of Moscow.

White troops near Petrograd.

МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruDenikin signed Directive No 08878 ordering a "march on Moscow" on July 3, 1919, a few days after the capture of the city of Tsaritsyn (future Stalingrad), a large industrial center and transport hub on the Volga. His troops' successes in the spring, as well as large-scale uprisings by Cossacks and peasants against the Soviet regime, made it possible to create a springboard in the south of the country for launching an offensive in central Russia. “Moscow was, of course, a symbol,” Denikin wrote in his memoir Russian Turmoil. “Everyone dreamed of 'marching on Moscow', and everyone was given this hope.”

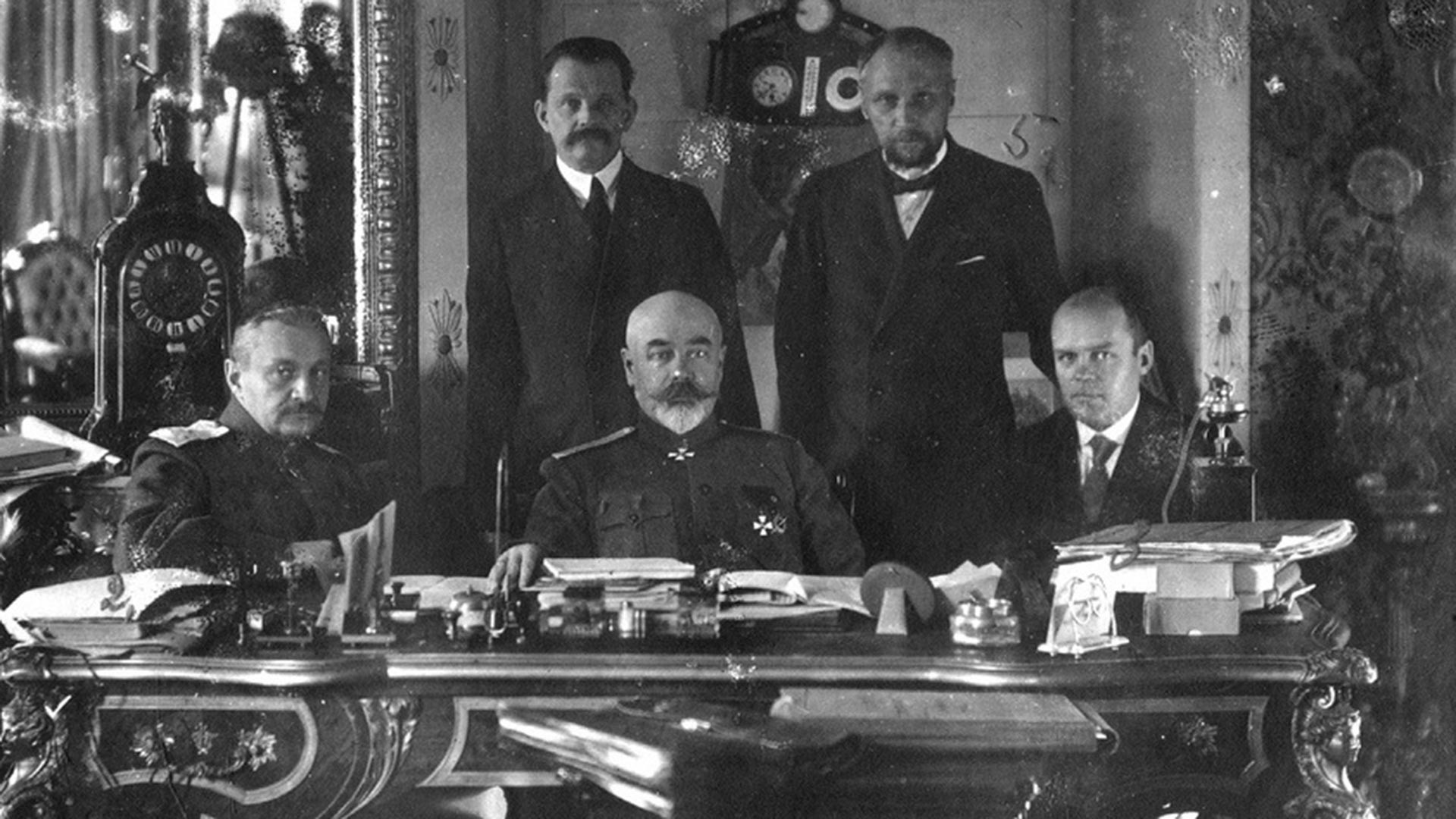

General Anton Denikin (C) in Taganrog.

Public DomainIn reality, not all of the White Guard leaders shared this optimism. The commander of the Caucasus Army, General Pyotr Wrangel, believed that the small forces of the AFSR (which numbered just 60,000 soldiers) were not up to such a campaign, and should have reinforced their positions and united with Kolchak, whose defeated armies at the time were retreating beyond the Urals. Many years later, already in emigration, he described Denikin's “militarily incompetent" directive as “a death sentence to the armies of the South of Russia”.

General Pyotr Wrangel in Tsaritsyn.

Public DomainNevertheless, in the course of a rapid offensive by the AFSR in the summer and fall of 1919, Poltava, Odessa, Kiev, Voronezh and Oryol were captured. White Cossack patrols appeared in the Tula province, just 250-300 km from Moscow. Having broken through to the rear of the Red Army's Southern Front, the Fourth Cavalry Corps of the Don under the command of General Konstantin Mamontov for more than a month sowed panic and chaos, burning warehouses, seizing weapons and ammunition.

The White Army soldiers.

Public DomainReinforced by soldiers from captured territories, the AFSR now had 150,000 people in its ranks. About 70,000 of them marched on Moscow, where the opposing side had over 115,000 troops, albeit inferior to them in combat training. Furthermore, the Red Army was greatly demoralized by a long string of defeats.

In Moscow, Lenin issued a proclamation "All out for the fight against Denikin!" warning that this was "one of the most critical, in all likelihood, the most critical moment of the socialist revolution". As the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Soviet Republic, Sergei Kamenev, wrote years later in his memoirs: “I cannot recall a more difficult situation during the entire Civil War.” On top of that, in early October worrying news came from Petrograd, where - to support Denikin's offensive in the south - General Yudenich's Northwestern Army, along with Estonian troops and the British fleet, had launched Operation White Sword to seize the former capital of the Russian Empire.

Parade of the Red Army on Red Square.

Pyotr Otsup/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruHowever, by mid-October, Denikin’s offensive began to run out of steam. Having seized vast territories from the Sea of Azov to the city of Oryol, the Whites did not have enough forces to effectively control them. As a result, in southeastern Ukraine, the so-called Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of the anarchist Nestor Makhno suddenly broke through the weakened AFSR positions and approached Taganrog, where General Denikin's headquarters was based. At the most decisive moment in the White offensive on Moscow, some regiments had to be pulled back from the front to save the situation in the rear.

Nestor Makhno (R).

МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruWhile the Whites were losing people, the Bolsheviks saw their ranks boosted. Help unexpectedly came from the Polish front. The principle of a "single and indivisible Russia", which Denikin and other leaders of the White movement were firmly committed to, did not sit well with the idea of a Polish national revival. Polish leader Józef Piłsudski was watching the successes of the Armed Forces of the South of Russia with apprehension. Although the Polish Army was successfully advancing in Byelorussia, in September he unexpectedly concluded a temporary truce with the Bolsheviks, which allowed the latter to transfer tens of thousands of soldiers to Moscow.

The Soviet armored train.

Viktor Bulla/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruAfter fierce fighting for Oryol in mid-October, the troops of the Red Army's Southern Front launched a large-scale counteroffensive. Despite the numerical advantage of the Reds, the Whites managed to retreat in an orderly fashion, avoided being surrounded and carried out counterattacks against the enemy. “Moscow already faded for us. Dark Russia with a dark expanse was driving hordes of Bolsheviks. Deep inside, many were feeling a sense of doom,” wrote officer Anton Turkul in his memoirs The Drozdovites under Fire.

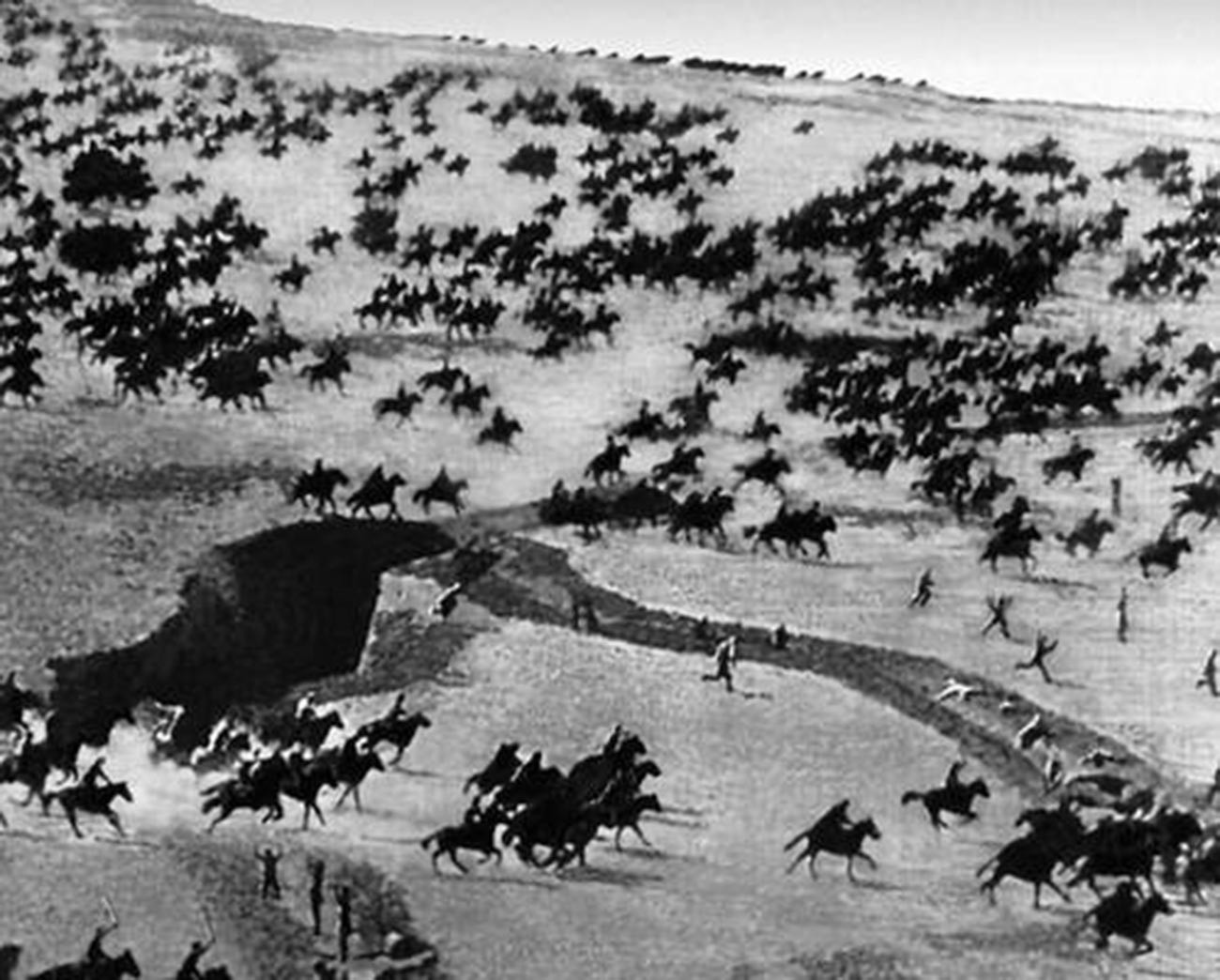

Red cavalry in action.

Public DomainThe White armies were defeated both in the south and in the north (in November, Yudenich was beaten near Petrograd). The AFSR's orderly retreat gradually turned into a panicked flight, accompanied by desertion on a massive scale. The last line of White defense in the south was Crimea, where they held out until November 1920. The White Movement would never get another chance of crushing the Bolsheviks as the one it had near Moscow in October 1919.

The White Army's evacuation Evacuation of the White troops from Crimea.

Public DomainIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox