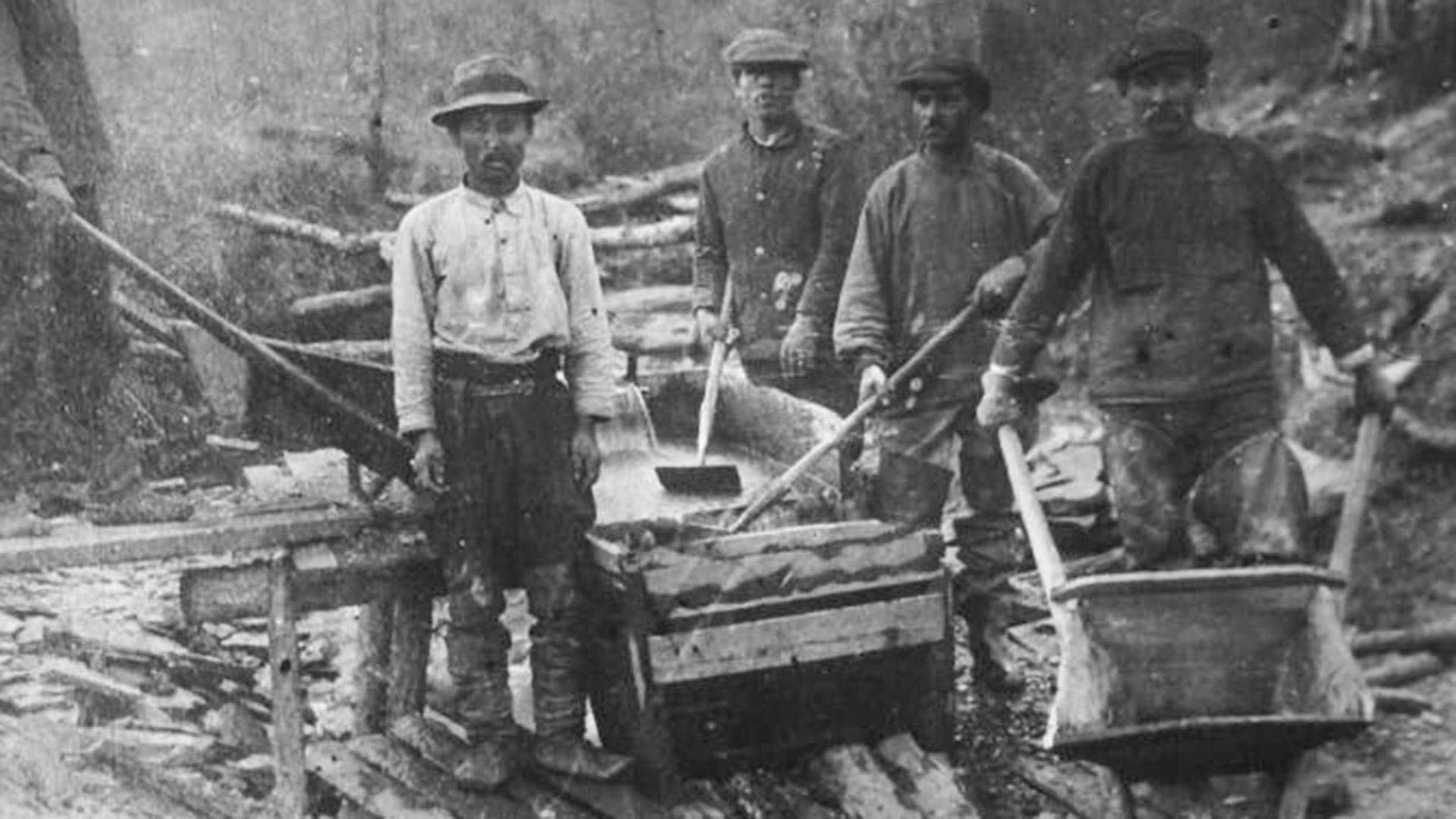

At the end of the 19th century a gold rush swept the Far East of the Russian Empire and neighboring northern areas of China. Tens of thousands of prospectors rushed to the many mines there to dig for gold, an activity that was not always legal.

Sometimes de facto states with their own president, legislative and judicial bodies, as well as law-enforcement authorities and armed forces, sprang up around these goldmines. The most famous among them was the Zheltuga Republic - also known at the time as "California on the Amur", or simply “Zheltuga”, which was founded by Russian prospectors of the precious metal.

This Russian "California" was established in Manchuria where unauthorized gold mining was punishable by execution under Chinese law. Taking advantage of the region’s lawlessness, Zheltuga residents easily ignored local laws. However, they were quite open to the idea of their "republic" joining the Russian Empire one day.

The history of ‘California on the Amur’ dates to spring 1883 when, on the River Zheltuga in Chinese territory, local people happened across several high-quality gold nuggets. The nearest large Chinese settlement, Aigun [today's Aihui], was hundreds of kilometers away, but the Russian settlements were right next door, just across the border on the other side of the River Amur. So, Russian gold diggers quickly moved in.

Initially, the Russian colony was a den of iniquity and anarchy. Apart from the prospectors, all sorts of adventurers, tricksters and bandits flocked there. Murders and robberies were commonplace.

There was also little organization in the mining of the gold. Instead of exploiting the goldmines in a methodical and orderly manner, the prospectors ruined deposits by recklessly digging random pits, rendering the deposits unsuitable for further exploitation. They were in a rush fearing that Chinese troops could arrive at any time and mete out justice on the "uninvited guests".

However, time passed and Peking did not react to the Russian colony that had sprung up on its territory. (It emerged later that the authorities simply didn't know of its existence.) The Zheltuga community concluded they could settle in Manchuria for the long haul and decided to bring discipline to the colony.

Zheltuga was divided into five districts: four Russian and one Chinese, who were the second most numerous ethnic group in the "republic". Two foremen were elected from each district, and they jointly oversaw the colony's administration.

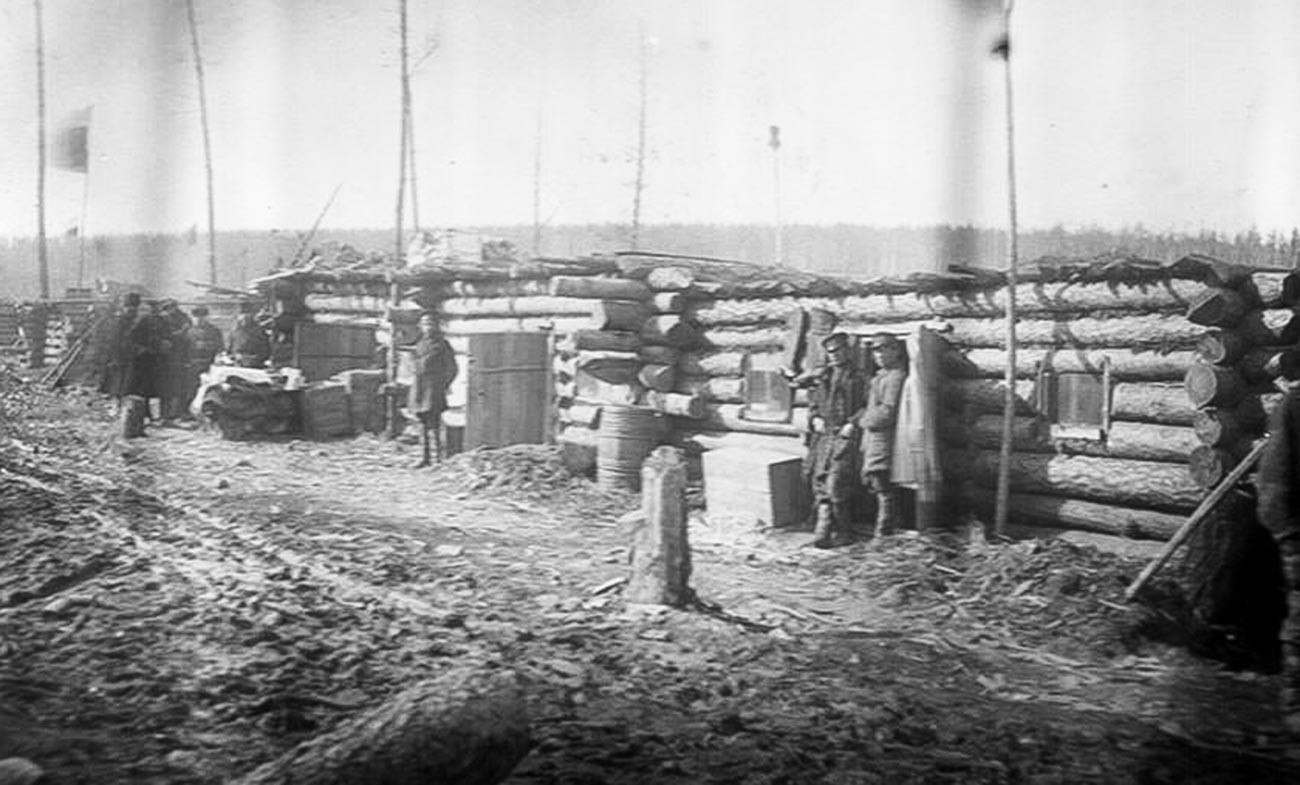

All political life in the colony took place on the central square - Orlovo Pole (‘Eagle’s Field’ in English), where the black and yellow "state" flag (symbolizing the union of land and gold) fluttered and a gallows stood for particularly unruly citizens.

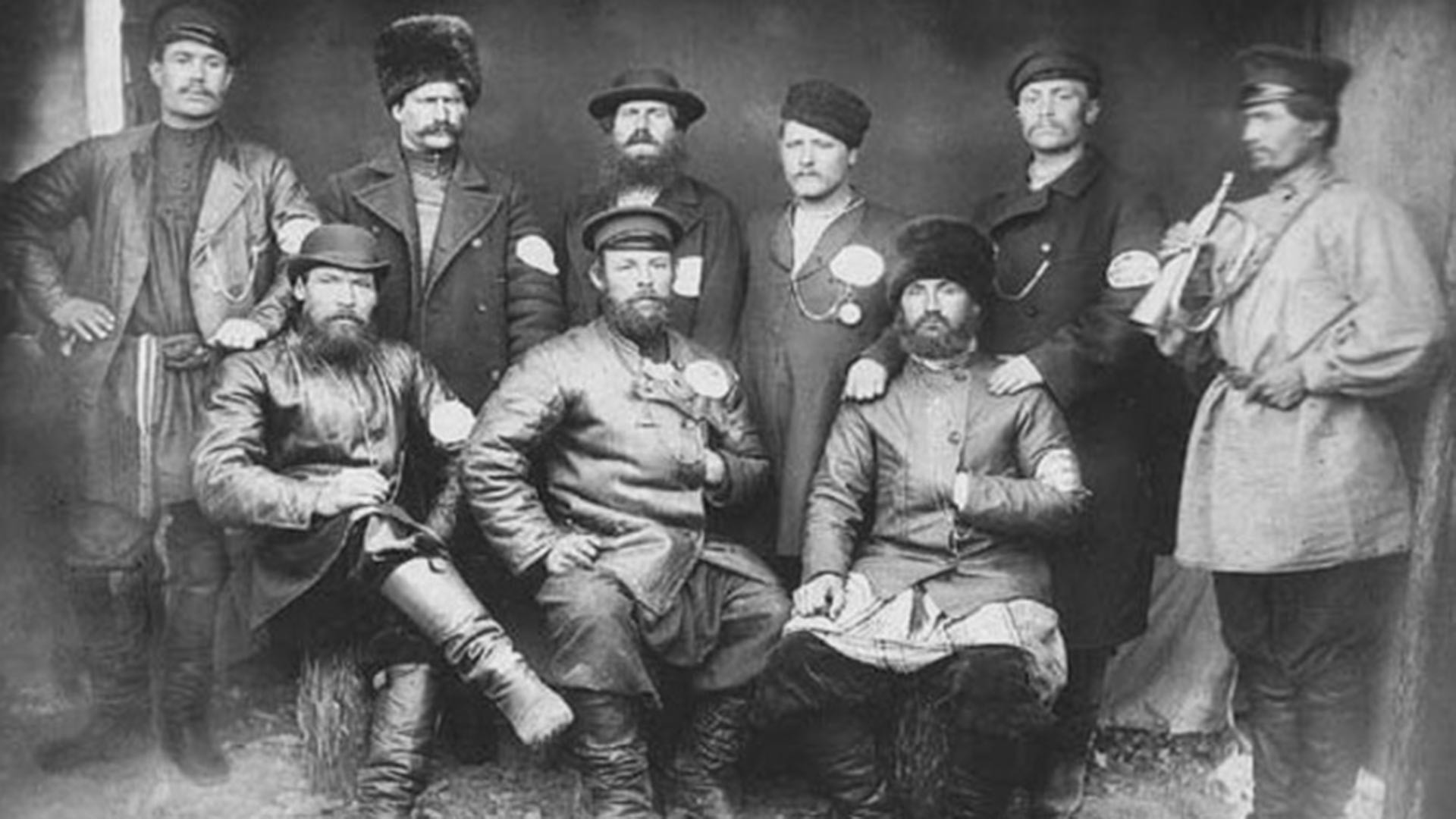

The Zheltuga Republic had its own court of law, treasurer and law enforcement agency numbering up to 150 men. The colony was headed by an elected president, the first of whom was Karl Johann Fasse, a native of Austro-Hungary, who decisively and ruthlessly imposed order in "California on the Amur". In a single day 30 people accused of murder were hanged.

"From the first days of the administration's existence", said an eyewitness, "many people who thought they did not need to take it seriously ended up badly. The first two weeks could, with justification, be called the time of the terrible floggings. Every day people were flogged for theft, sodomy, and so on - in brief, floggings were held from morning till night for every kind of wrongdoing, and it was only after these measures had been taken against those with a penchant for other people's property or for extreme thrills that they eased off a bit."

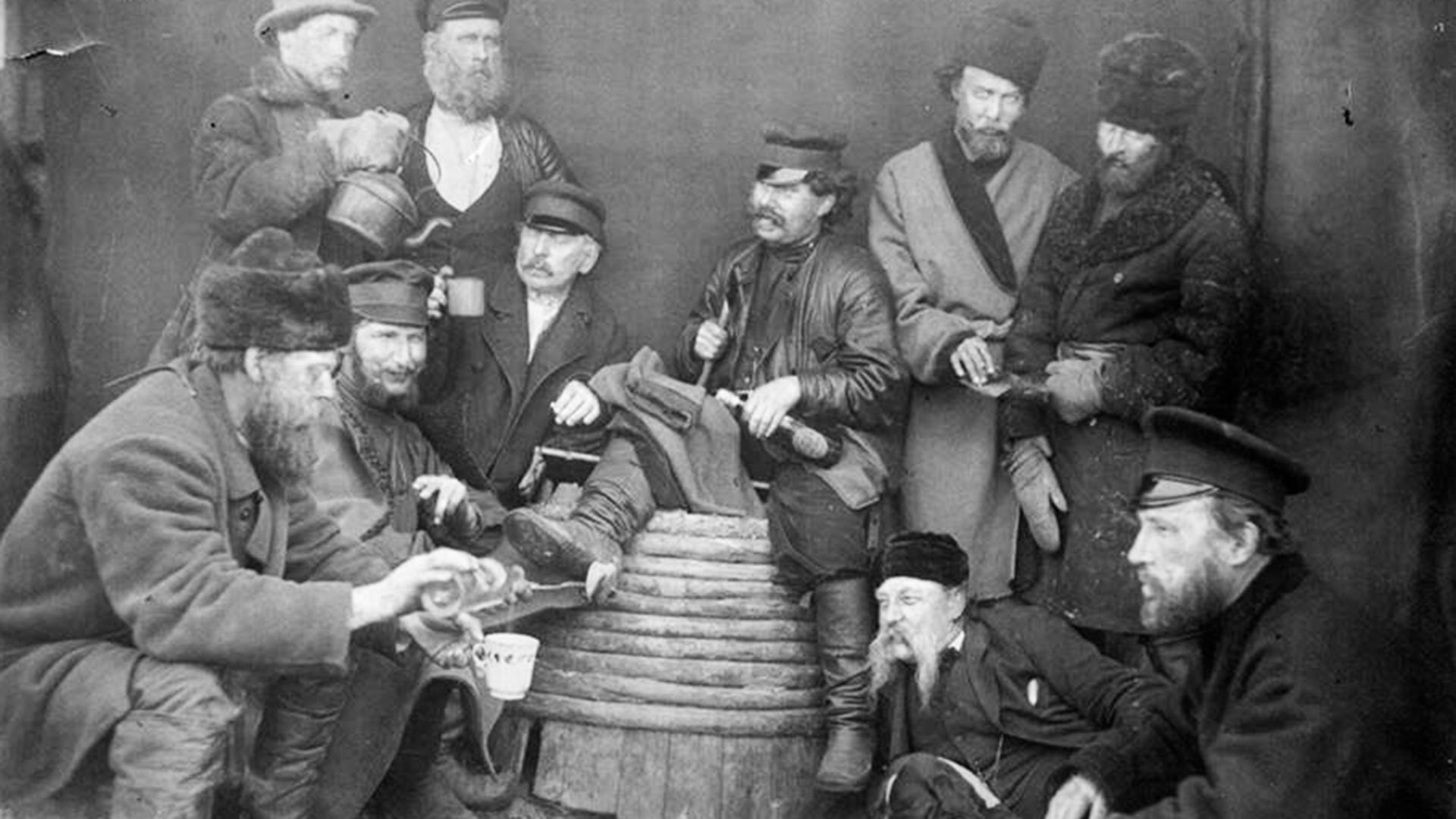

After order was imposed in Zheltuga the colony began to grow rapidly. In the course of a year the population soared from several hundred to 9,000. The peak number of inhabitants during the period of the settlement's existence was 20,000.

Since Russians were the majority in the "republic", Russian became the official language. Communication with the Chinese "Californians" was conducted in a simplified language common to the border regions, so-called ‘Kyakhta Pidgin’.

Like mushrooms after rain, shops, bath houses, jewelry shops, taverns, gambling houses and hotels for the numerous Russian and Chinese gold traders sprang up. The colony even had its own theater, photographic laboratory, menagerie, a whole troupe of circus performers and two orchestras. They all dutifully paid their taxes, which were spent on social needs. For instance, the colony was able to open its own hospital from these funds.

The Zheltuga Republic grew and prospered. Gold was literally underfoot and was used as a means of payment alongside cash. At the local Chita Casino, prospectors coolly lost sums that could otherwise have allowed them to live comfortably for the rest of their lives.

Almost a year after the birth of "California on the Amur" the Chinese authorities finally got wind of its existence. The amban (governor) of Aigun started to bombard the leadership of Amur Region with requests for assistance to expel the intruders. Within a short space of time a letter of protest was sent to the Tsar by Empress Cixi.

Officials in Russia were well aware of the existence of the Zheltuga Republic and even actively collaborated with it. Officially, they told the Chinese they had never heard of such a "state", and if such a thing did exist they were not empowered to interfere in China's internal affairs.

Russia effectively gave China carte blanche to deal with the "Californians" however it saw fit. At the same time, Cossack detachments were sent to Zheltuga with orders to warn the prospectors that they could expect no state backing or military protection, and their best way out would be to leave Chinese territory immediately.

In February 1885 the first reconnaissance detachment of Chinese troops appeared in the environs of Zheltuga. On August 18 that year a Qing officer turned up at the colony to demand the evacuation of the area within eight days. Although he only had 60 soldiers under his command, the colony started to disperse.

After the deadline passed, the Qing detachment entered an empty Zheltuga, burned down a couple of dwellings and beheaded several Chinese who were hiding here. After they had gone, however, the "Californians", who had been biding their time nearby, started to return.

Learning soon afterwards that life in the "republic" was continuing as before, Peking sent a detachment of 1,600 soldiers in January 1886 with orders to burn the colony to the ground, drive the Russians to the other side of the Amur and execute the Chinese living in the settlement for illegal gold extraction. This time it was useless for the inhabitants of Zheltuga to try to outsmart the Chinese. So as not to worsen relations with Russia, the citizens of "California on the Amur" were given free passage home - something that can’t be said for their fellow Chinese prospectors.

"Hardly had the Chinese soldiers spotted the inhabitants of Zheltuga moving across the ice of the Amur when they set upon their defenceless countrymen," according to Alexander Lebedev, historian of the "republic", writing in 1896. "Of course everyone scattered in different directions as best they could; they ran off over banks of snow and across hollows in the ground; they clambered over blocks of ice or hid behind them where they were large enough to provide shelter. The frost chilled their limbs; hunger and exhaustion sapped their strength; the runaways fell, picked themselves up and ran on again in a bid to reach the river bank and hide in the Cossack station. But there was no deliverance there either. They were butchered and tortured on our side of the river too; people would be dragged out of a crowd of Russians and tormented in the streets; Russian houses were broken into and the victims dragged out. It was a terrible, monstrous, savage carnage."

After the destruction of "California on the Amur" the prospectors dispersed throughout the Russian Far East. Unwilling to part with their lavish lifestyle, they attempted to found new free "republics" at other gold mining sites, but were relentlessly driven away by local authorities. The problem of widespread illegal gold mining in Russia was only finally resolved by the Bolsheviks in the early 1930s.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox