There was only one moment in history when Lenin’s Mausoleum on the Red Square could have been left without its tomb and there could have also been a string of open graves along the Kremlin wall. That moment came after the death of Joseph Stalin on March 5, 1953.

When Stalin died, there arose the question of what to do with his body. The option of “just burying” it was not even on the table, while the stream of those who wanted to pay their last respects to the late Soviet leader showed no signs of thinning weeks after his death and had even claimed several lives. For a while, Stalin’s body was placed in Lenin’s Mausoleum, with the two tombs standing next to each other and the name STALIN in large letters appearing underneath LENIN above the entrance.

But the already cramped mausoleum was supposed to serve only as a temporary solution. The very next day after Stalin’s death, the papers published a party decree announcing plans to set up a pantheon in Moscow.

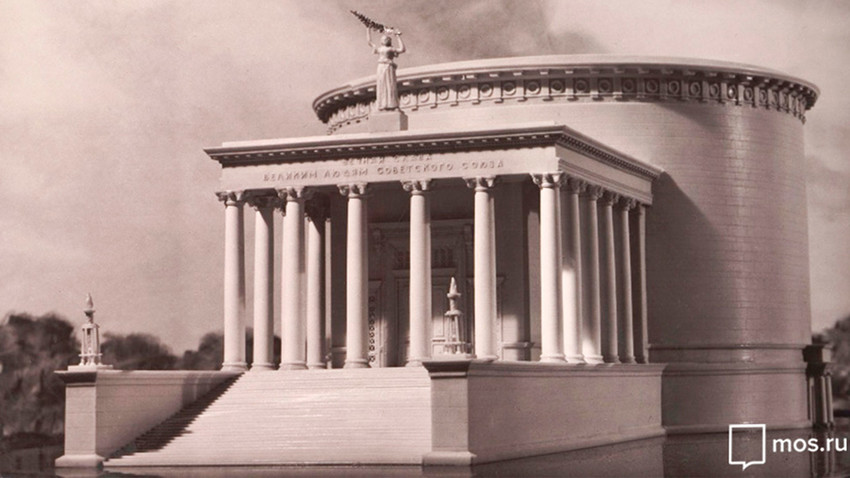

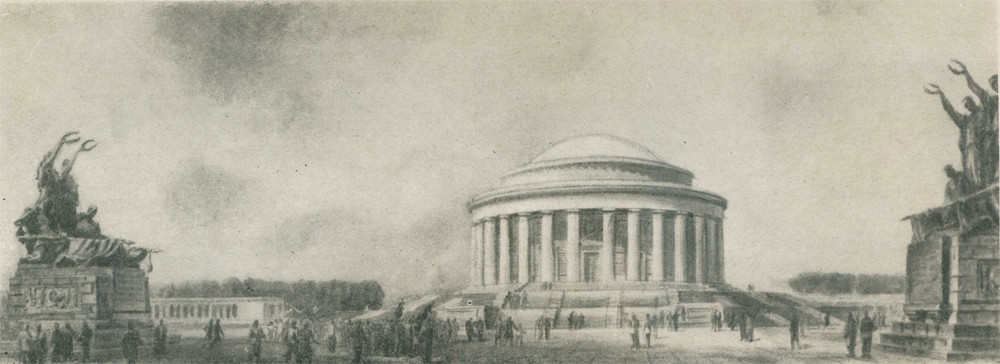

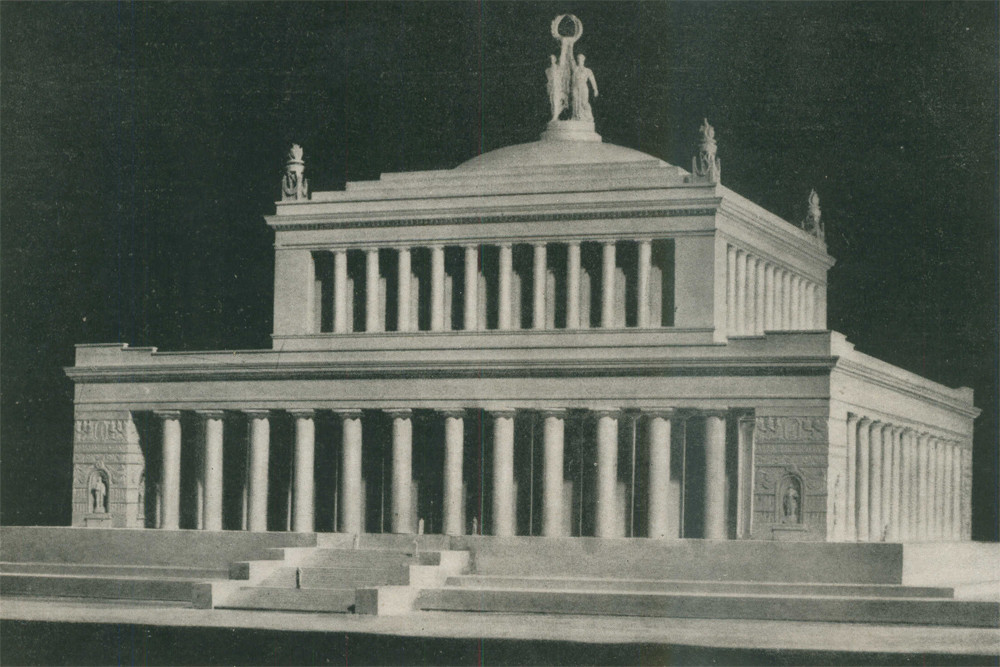

The idea was to build a Pantheon similar to Rome’s “temple of all gods”. It was supposed to accommodate the tombs of all “the great people of the Soviet country”, those who were buried by the Kremlin wall, as well as the tombs of Lenin and Stalin that were to be moved to the new pantheon in a special ceremony. Just as the original Pantheon, the Bolshevik necropolis was supposed to be an impressive example of monumental architecture. Everything about it - the sculptures, the bas-reliefs, the plaques, the paintings, the mosaics and especially the size of the place– had to be grand.

True to the principle “the more the better”, the authors of the project envisaged an area of 500,000 square meters for it, larger than the Vatican! There remained two conceptual questions though: what exactly should the necropolis look like and, most importantly, where should it be located?

Thus, in the same official announcement, a competition was launched for the best architectural design. The competition was open not only to professional architects, but also to ordinary citizens. The deadline for submissions was November 1, and the USSR Academy of Architecture was inundated with designs, including some quite extravagant ones.

Initially, the most attention was focused around a project by an architect named Nikolai Kolli, who had designed several metro stations, stadiums, administrative centers and had worked with the famous French architect Le Corbusier. He suggested building the future memorial complex in the style of Soviet monumental neoclassicism inspired by the Roman Pantheon and placing it directly opposite the Kremlin, on the other side of the Red Square. Except that to accommodate it, it would have been necessary to pull down the GUM department store and a whole neighborhood of historical buildings in Kitay-Gorod, including the Polytechnic Museum.

However, for the Communist Party leadership, the main snag turned out to be not this, but the fact that the government stand on the pantheon would have been opposite from the existing mausoleum, so during parades columns of troops would have to march with their eyes to the right, which was against the established order. That is why other options for where to erect the pantheon began to be explored.

For example, there was a proposal to build the pantheon across the river opposite the Kremlin, near Sofiyskaya Embankment. Not far from it, one of the most ambitious urban development projects - the Palace of the Soviets - had long been planned: a gigantic skyscraper with a giant statue of Lenin at its top. However, in the end, this location was abandoned, too.

Later, the party issued a clarification: “The pantheon is to be built in Moscow, 3.5 km south of the new building of Moscow State University on the grounds of the Vorontsov Vitamin Institute.”

Among the other submissions for the pantheon competition, there were some quite controversial ones. One of them, which came from a common worker, proposed building two giant statues of Lenin and Stalin, who would be holding hands and looking into the distance, “into the bright Soviet future”, and placing the necropolis... inside them. But the design for this pantheon looked more like a huge chest of drawers, as the ashes of the late communists were supposed to be stored in niches on the outer surfaces of the two statues.

Other submitted designs had a huge globe instead of a dome or proposed the Pantheon in the form of a huge egg, set (for some reason) bottom up. None of those visions were ever realized.

In April 1955, Soviet writer Alexander Tvardovsky wrote in his diary that the idea of a pantheon “seemed to have sunk into oblivion, lost amid more pressing matters”. In reality, the project was canceled without any announcement or explanation.

The reason for that soon became obvious. Just a year after Tvardovsky made that entry in his journal, the famous 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union took place, at which Nikita Khrushchev delivered the famous speech denouncing Stalin and his dictatorship. Stalin monuments all over the USSR began to be pulled down and, obviously, there was no longer any talk of building a mausoleum for him. It was also then that there began a campaign against “architectural excesses” associated with Stalin's rule, so many other projects, including the ambitious Palace of the Soviets, never saw the light of day.

In total, Stalin’s body spent seven years in the mausoleum next to Lenin’s mummified corpse and, in the end, was moved not to a dedicated new necropolis, but into a grave by the Kremlin wall. Furthermore, it was reburied in secret and at night, so as not to provoke Stalin’s most ardent supporters.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox