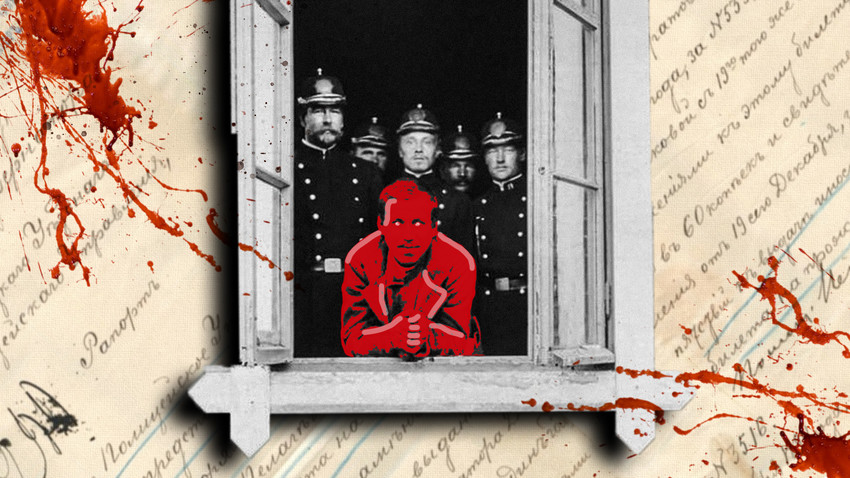

Soviet actor Evgeny Evstigneev in the role of fraudster Koreyko, a character based on Konstantin Korovko. Taken from a movie The Golden Calf (1968)

Mikhail Shveytser/Mosfilm, 1968A man named Konstantin Korovko was among the most lucky fraudsters ever in Russia – most of all, because we don’t even know the place nor the time of his death – a rare thing for a man who stole millions. Born into a Cossack family in 1876, Korovko received an unusually good education – he became an agronomist and industrial technologist, graduating in 1906. But his main interest was in collecting money from investors and never returning it.

In the 1910s, he lured rich country landlords into commercial partnerships, advertising the organization of some leather mills, salt mines, or oil wells in the Northern Caucasus. Korovko fascinated his would-be shareholders with big photographs of cargo cisterns and steamers. The enterprises he advertised never existed – but Korovko’s office in St. Petersburg had beautiful oak tables, his clerks worked on Swiss typewriters – everything to impress the partners. By 1912, Korovko amassed several million rubles in different partnerships – when an average monthly salary was just 30-40 rubles!

St. Petersburg, Nevsky prospect, where Korovko had his main office

Archive photoIn 1912, Korovko was arrested – after one of the shareholders went to the alleged site of the salt mines and found nothing there. However, Korovko’s personal bank account contained no money. During the years his enterprises existed, he either spent the money or hid it somewhere. In court, Korovko blamed his partners for interrupting his activity – he said he was still preparing to build the mines and the mills they gave him the money for. Meanwhile, as they were only shareholders, they shared the responsibility for their money, so Korovko wasn’t charged with theft – he only spent 2 years in prison during the trial.

After the Revolution, Konstantin Korovko escaped Russia to Romania, and he disappeared from the record after that. There were rumours that he later surfaced in Argentina where he became a meat trader.

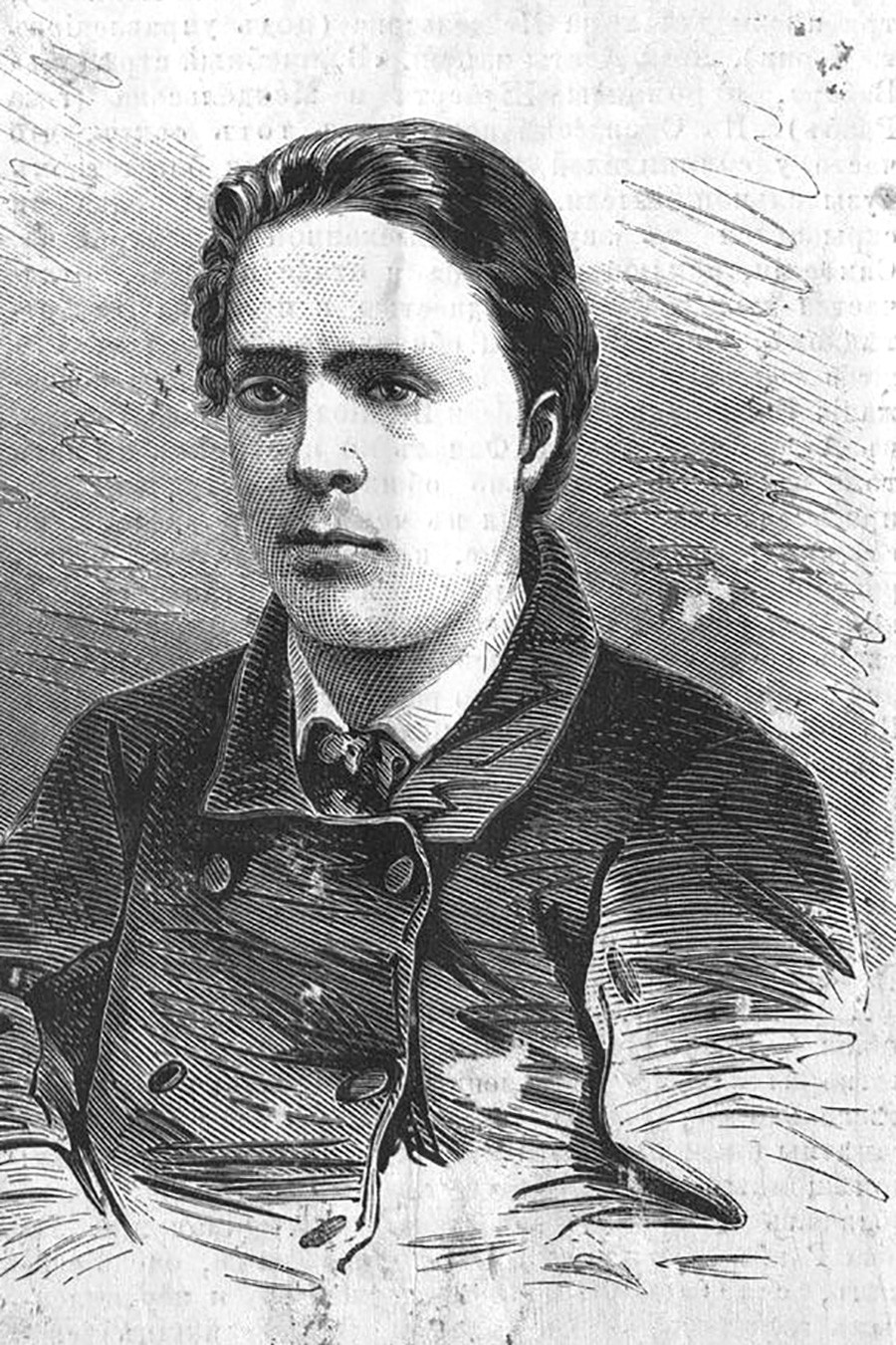

Vitold Gorsky, 1869

Drawing by N. I. Sokolov, engraving by L. A. SeryakovVitold Gorskiy killed an entire family because he needed money, but didn’t take the money. One of the most monstrous murders of Tsarist Russia was committed by a 18 year-old gymnasium student on March 1, 1868 in Tambov.

Gorskiy was teaching the 11 year-old son of Ivan Zhemarin, a wealthy Tambov merchant. Apparently amazed at the family’s wealth, he stole a revolver from his acquaintance, and ordered a heavy iron rod from a blacksmith. When Ivan Zhemarin and his wife were away from home, Gorskiy slaughtered his pupil, shot Ivan Zhemarin’s mother, a yard keeper and a kitchen maid. When Zhemarin’s wife suddenly returned home with her 4 year-old son and a housemaid, Gorskiy killed them, too, and left the building, not taking any money or expensive jewelry.

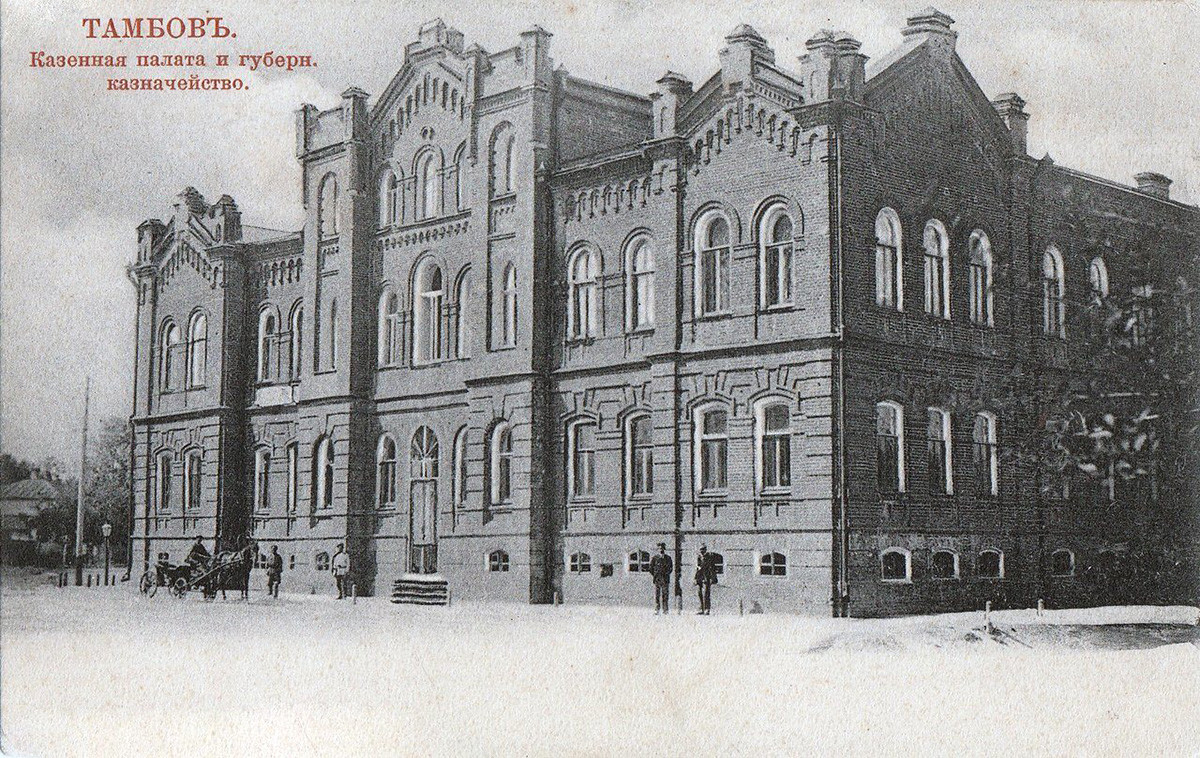

The Treasury building in Tambov – a reconstructed house of Zhemarin, where the murder happened

Archive photoHe was soon apprehended as the most obvious suspect. In court, Gorskiy said he didn’t take anything from the house, although he confessed to the murder. After being sentenced to death, Gorskiy filed a plea where he said although he committed the murder for the purpose of robbery, but did not use anything from of Zhemarin’s property "under the influence of a sense of remorse and regret for the victims of the crime.” Gorskiy also cited “the extreme poverty of his family” as the reason for mass murder. His plea was refused. But Emperor Alexander II commuted his death sentence to a lifetime of hard labor.

This gruesome story rang very loud in Russian society of the era, and it is mentioned multiple times by the characters of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot.”

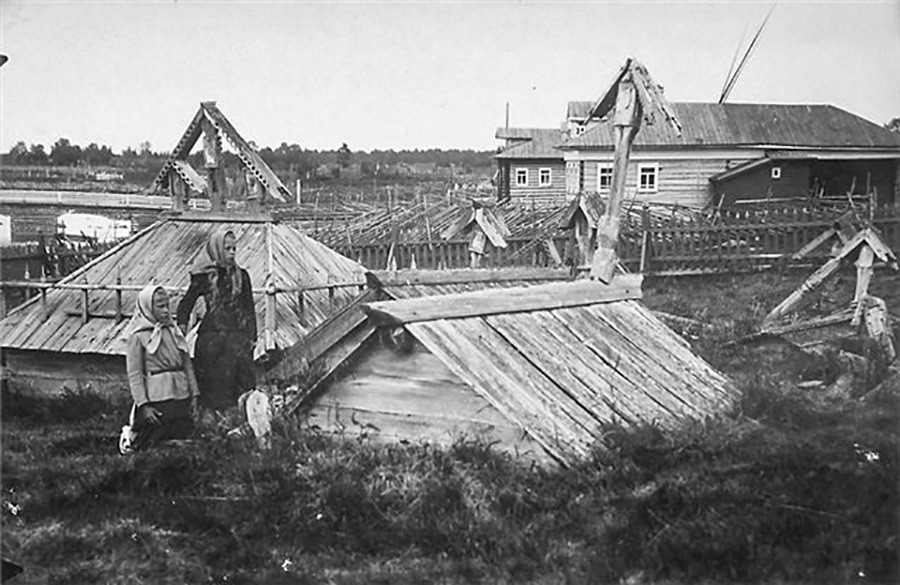

An Old Believers' graveyard with wooden covers for tombstones, White Sea shore, 1917

Archive photoMany people in Russia were hostile towards the Imperial Census of 1897, especially the least literate among the peasantry. There were panicked rumors that the Census was performed to relocate the peasants, or to make them pay more tax. The Old Believers detested the Census as the ‘business of the Antichrist,’ especially wary of the fact that a number was assigned to each person who passed the census. Some of the most fanatic Old Believers decided it was time to leave this world.

On December 23rd, 1896, in the region of Tiraspol (currently, capital of Transnistria, a breakaway state in Moldova), nine Old Believers sang a burial rite to themselves, laid in a grave and waited for their fellow Old Believer Fyodor Kovalev to cover the grave with bricks. Kovalev’s wife Anna with two baby daughters were among the ones buried. All this was done at the request of the buried. Four days later, Kovalev buried six more people, in February 1897 – four more, including his sister, and finally on February 28th, 1897 – six people, including his mother and brother.

Russian Old Believers

Archive photoKovalev was arrested and jailed in April 1897, but the details of his crime weren’t made public – the authorities didn’t want to draw public attention to the dire ignorance the Old Believers were living in. In 1898, Emperor Nicholas II ordered Fyodor Kovalev into a Russian Orthodox convent in Suzdal, where he lived under strict observation. In 1905, Kovalev was set free. He remarried and had three sons.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox