In St. Petersburg society, Feliks Yusupov was known as an extremely extravagant figure, prone to outlandish antics and commercial endeavors. Humanity loves to make movies about people like that - and that’s exactly what happened. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) at one point released a hit movie that scored an Oscar nomination for best screenplay and was lauded by critics. However, it was not to Yusupov’s and his wife’s liking - and the Russian emigrants ended up becoming a nightmare for the American movie industry.

The Yusupovs were among the wealthiest families in the Russian Empire, owning mansions, palaces, land, factories and exquisite jewellery collections. In the four centuries of the clan’s existence, there were military commanders, secret confidants, governors, ministers and patrons. In short, a reputable name that Feliks began to take to new “heights” at the start of the 20th century, threatening to undo its legacy.

After the death of his older brother Nikolay, who was killed during a duel, Feliks became the sole heir of a large inheritance, while continuing to be the source of family scandal and public gossip, with his own relatives often claiming he brought “shame” to the family name.

At 17, for example, he decided to cross-dress as a woman, putting on a dress and makeup, and performed at a luxurious Petersburg cabaret, just for the fun of it. After seven such performances he was finally recognized by a member of the audience who knew him personally, spotting the family diamonds. Then, in 1909, he left to study at Oxford and, in three years of living in England, gained infamy for Devil worship, while single handedly being responsible for a fashion in black rugs, and barely avoided becoming the main suspect in the kidnapping of Prince Christopher of Greece. He also attempted to steal a cow from a forgetful old woman (a cow he actually legitimately bought earlier) and managed to end up being shot at. There were also crazy parties - unheard of at the time in English society.

Yusupov Palace

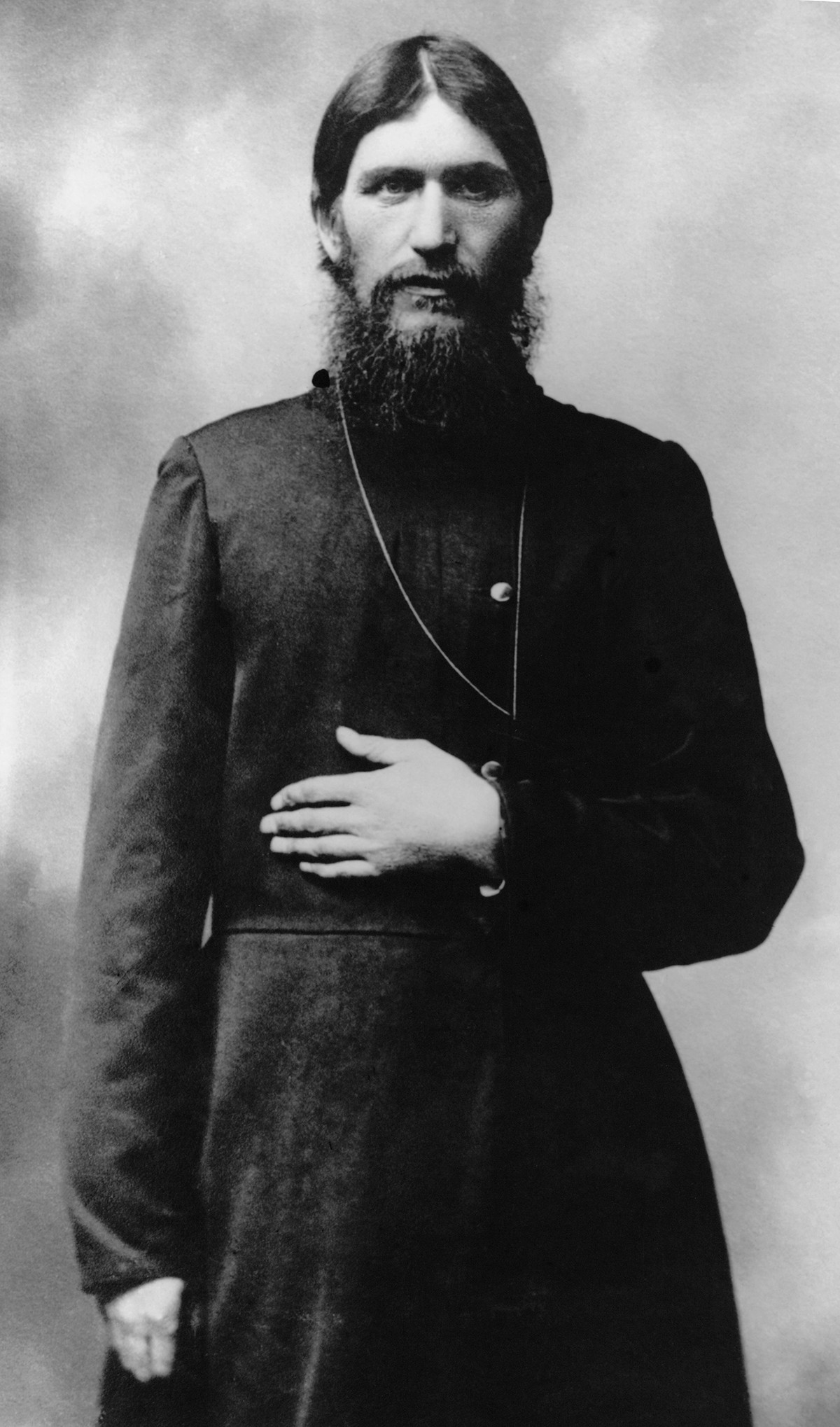

Public DomainHaving returned to Russia, Feliks began to realize the responsibility that lay on his shoulders as the sole heir of the Yusupov name. With that, he began to think as a politician. At 29, this led him to conspiring to kill the tsar’s favorite monk - Grigory Rasputin. In 1916, as we know, the plan was realized. Feliks personally shot the “saint” in the chest, after a bungled attempt at cyanide poisoning. “I became fully convinced that he harbors in him a great evil and the main reason behind Russia’s misfortunes: with Rasputin gone, so will the Satanic power that holds the Tsar and the Empress in its grip,” Yusupov wrote in his memoirs.

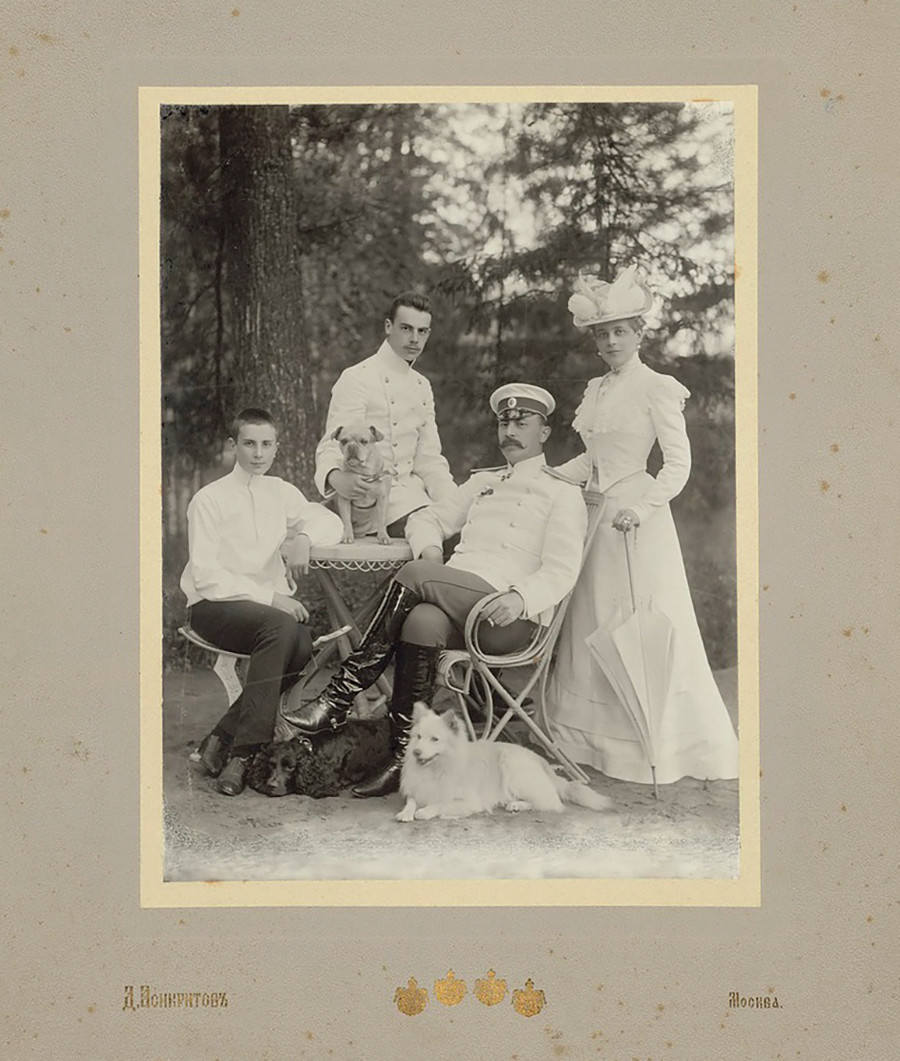

Yusupov family

Daniil Asikritov / State Museum-Estate "Arkhangelskoye"However, he turned out to be wrong. Autocracy was not resuscitated with Rasputin’s death and, after the October Revolution, Yusupov fled - first to England, then France.

The Russian prince got away with murder. Two years prior to his crime, he married Nicholas II’s niece, Princess Irina Romanova. As angry as they were at their favorite mystic’s murder, the Royal family could not bring itself to issue a serious punishment to one of their own. Besides, many supported Yusupov’s actions, judging them to be in the country’s best interest.

With their family jewels and two Rembrandt paintings in hand, Feliks and Irina left Russia, but, despite the modest fortune, they were able to preserve their bohemian lifestyle and even financially support other Russian emigrants with charity work, which they engaged in during their stay in London.

Grigory Rasputin

Public DomainThings went downhill for the Yusupovs in France in the 1930s. Russians had much fewer sympathizers in the world at the time and money was becoming scarcer by the day. The jewels had to be pawned and the Rembrandts were sold to an American collector named Joe Videner. The Yusupovs managed by then to open their IRFE fashion house and launch a perfume line, while also trying their hand at the restaurant business, but it was a far cry from the financial comfort they enjoyed previously. There were days when Feliks Yusupov would not be able to pay for a lavish meal, which was a force of habit, and had to rely on their passport to solve the matter - nobility dined for free.

Princess Irina and Prince Felix Yussupov

Public DomainBut, soon thereafter, fortune finally smiled on the family: In 1932, Hollywood’s MGM studios released ‘Rasputin and the Empress’ with John Barrymore (the grandfather of actress Drew Barrymore). The Yusupovs found the movie to be offensive and sued the studios in London.

Their claim revolved around spreading false information, insult and slander. The move told the story of Rasputin’s rise and death and his relationship with the Royal family and his followers. Rasputin’s death is staged by one Pavel Chegodaev, whose appearance looked to be the spitting image of Yusupov. However, the Yusupovs really did not mind - it’s not like the true identity of Rasputin’s killer was a well guarded secret (Feliks even wrote a book about it titled, ‘The End of Rasputin’).

According to the movie, the prince’s fiance, Natasha, was raped by Rasputin, then becoming his concubine. Yusupov considered this an affront to his wife Irina - the parallels were quite clear. Speaking of which, the first draft of the movie even had the original names!

Having been taken to court, MGM had to apologize and publically address the situation, saying that Princess Natasha was a fictional character that had nothing to do with the real Princess Irina Yusupova. But the damage was done and the jury sided with the Yusupovs, reaching a guilty verdict, which resulted in the studio being compelled to pay the sum of 25,000 pounds to the family.

What’s more, the studio had to pay another 75,000 pounds for the right to screen the picture, albeit already having to cut out 10 minutes that were deemed especially offensive to the princess’s image, bringing the total sum to 100,000 pounds, equivalent to about $3 million today, which ensured a very comfortable life for the Yusupovs!

It was these proceedings that lay the groundwork for the practice we see used to this day, where, at the start of every movie, you see the disclaimer with the phrase along the lines of “all persons, living or dead are entirely fictional...”.

Later, not long before Yusupov’s death, he tried to play the same card again, suing the broadcast company CBS - again for slander - to the tune of $1,5 million, for the horror movie ‘Rasputin the Mad Monk.’ He lost that time, however.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox