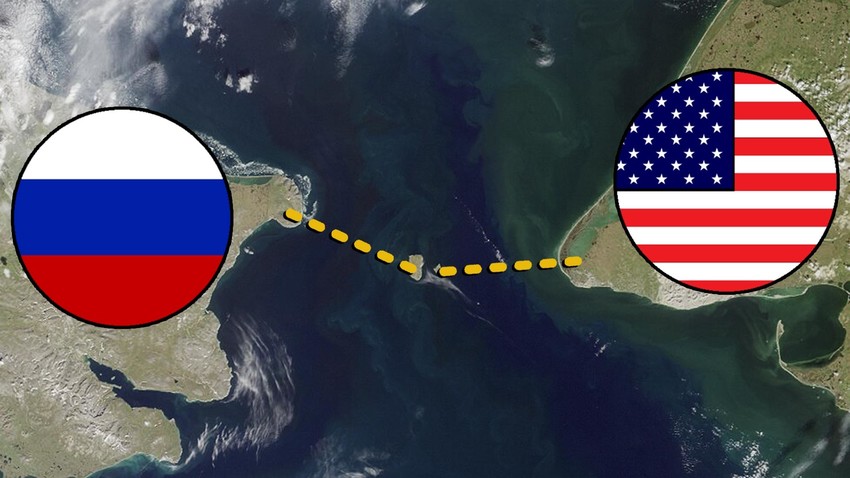

For centuries, various individuals, corporations and even governments of Russia and the U.S. lobbied for a bridge or a tunnel over the Bering Strait that would connect the two continents of North America and Eurasia.

Yet, the grandiose project never materialized, hindered by doubts, lack of funding - and wars.

“Czar Authorizes American Syndicate to Begin Work,” reported the New York Times on August 1, 1905.

According to the publication, an American syndicate had received the green light from Russian Tsar Nicholas II to begin implementing the Trans-Siberian-Alaska railroad project that was to connect the U.S. to the Russian Empire via Alaska and Chukotka, the two regions belonging to the U.S. and the Russian Empire, respectively, and divided by a narrow strait.

Portrait of Tsar Nicholas II.

Public domainFrom $250 million to $300 million were to be allocated to finance the ambitious enterprise, the report said. However, the plan was doomed to fail, as a war and a revolution would be looming over the Russian Empire in a few years.

A bridge or a tunnel across the Bering Strait, a narrow body of water lying between American Alaska and Russian Chukotka, is an old idea that dates back to the late 19th century.

Alaska, 1918.

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty ImagesBack in 1890, the first governor of Colorado Territory William Gilpin put forward a futuristic proposal to construct the so-called Cosmopolitan Railway, a grand system of interconnected railways that would encircle all of the world’s continents with the center in Denver, Colorado.

William Gilpin.

Public domainAmong other things, governor Gilpin was a futuristic writer and his idea of the Cosmopolitan Railway might have preceded its time.

Yet, the idea did not die: in 1904, a syndicate of American railroad magnates proposed to construct a tunnel under the Bering Strait from the Cape of Wales in Alaska to the Cape Dezhnev, the easternmost mainland point of the Russian landmass.

The precarious state of Russian politics at the time must have averted the grandiose plans of the American magnates. In 1905, the same year Tsar Nicholas II reportedly approved the proposal, the first Russian revolution broke out and shook the country. Within the next ten years, Russia would experience multiple revolutions and a total reorganization of social and political life, as well as the emergence of a whole new political entity — the USSR.

Border guards of ex-USSR patrolling along the Provideniya Bay and Bering Sea.

Robert Wallis/Corbis/Getty ImagesThere was simply no time, money, certainty in the future, or political will to launch the ambitious infrastructure project.

In 2005, Reverend Sun Myung Moon, a Korean-born self-described messiah known for his ambivalent business ventures, proposed something not so original, but truly dramatic: a tunnel connecting East and West.

Sun Myung Moon.

Owen Franken/Corbis/Getty Images“For thousands of years, Satan used the Bering Strait to separate East and West, North and South, as well as North America and Russia geographically. I propose that a bridge be constructed over the Bering Strait, or a tunnel be dug under it,” Moon reportedly said.

Moon did not shy away from lavishly advertising his idea: “Some may doubt such a project can be completed. But, where there is a will, there is always a way—especially if it is the will of God. The science and technology of the 21st century render it possible to construct a tunnel under the Bering Strait. This tunnel can help make the world a single community at last,” Moon continued.

Neil Bush.

Mark Reinstein/Corbis/Getty ImagesEmbarking on a tour around the world to promote his idea and secure funding, the self-described messiah found some unexpected allies, including, reportedly, Neil Bush, the son of U.S. President George H. W. Bush, who reportedly traveled along with Moon on parts of his journey to promote the venture.

Yet, despite publicity and support of high-ranking people in various places in the world, the project had never gained enough momentum so that its construction would eventually begin.

Perhaps, lack of decisive funding can be explained by the fact that the tunnel’s hypothetical economic benefits are rather uncertain, as it is supposed to connect Alaska with the least populated part of Russia.

Diomede Islands in the Bering Strait.

Jacques Langevin/Sygma/Getty ImagesBesides, severe weather conditions posed a serious challenge, making construction only possible during five months of the year.

Given that the bilateral relations between the U.S. and Russia have deteriorated in recent years, the tunnel or a bridge across the Bering Strait seems to be an all too distant prospect. Though, one might be sure someone will raise the question again in the future: Can we finally connect the two continents?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox