When young Vladimir Putin — according to his official biography — went to a public reception office of the KGB to find out how to become an intelligence officer, he was told a university degree or service in the army would be required.

The Soviet KGB also actively recruited staff and agents, sometimes even against their will.

Although working in the KGB promised certain benefits, the ranks of the committee were filled with people of various backgrounds.

Since the KGB was a complex institution that incorporated multiple directorates — each with its own professional responsibilities — there was a need to fill vacancies with people of various talents and specializations.

A young Vladimir Putin in a KGB uniform.

Global Look Press“The KGB of the USSR was a large and complex-structured organization. For example, the work of the First Chief Directorate (intelligence) was fundamentally different from the territorial [directorates] (counterintelligence, 2-6 directorates). There were many specialized, combat, and technical units, military counterintelligence, border troops (with its own intelligence), special communication [directorate], the 7th and 9th divisions [responsible] for security [of party officials],” said Andrei Milekhin, a former officer at the KGB.

Milekhin said asking who could land a job in the KGB missed this important point: the KGB was a large organization and needed all sorts of people.

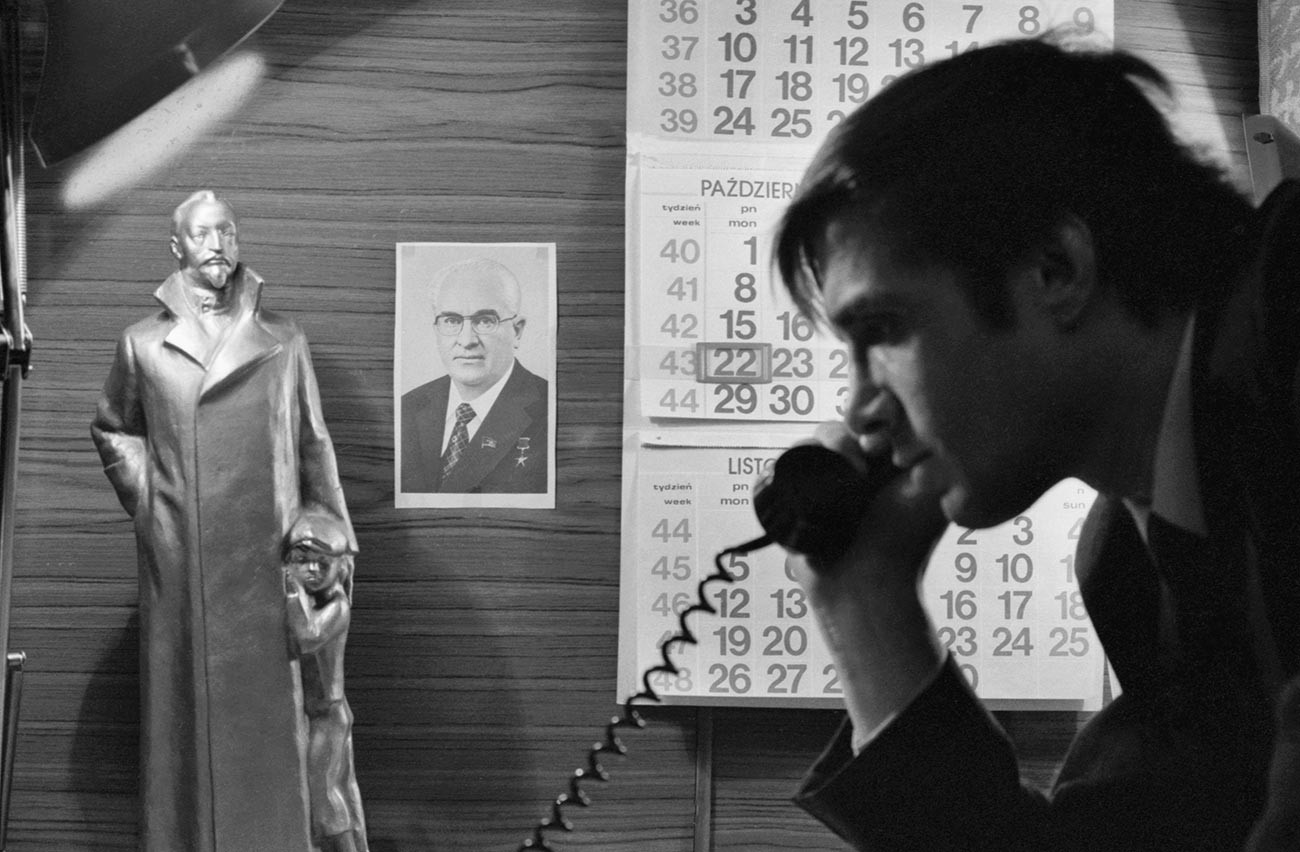

KGB rookies' training.

Pavel Maksimov/TASSAt the same time, the powerful and highly secretive institution viewed strangers and unsolicited candidates with suspicion.

Instead, KGB recruiters worked hard to sieve potential candidates in many other places, not related to the secret police: universities, the army, factories, etc.

Recruiting officers observed and assessed potential candidates at their places of work. Most often, future KGB officers did not even suspect they were being assessed for work in the KGB.

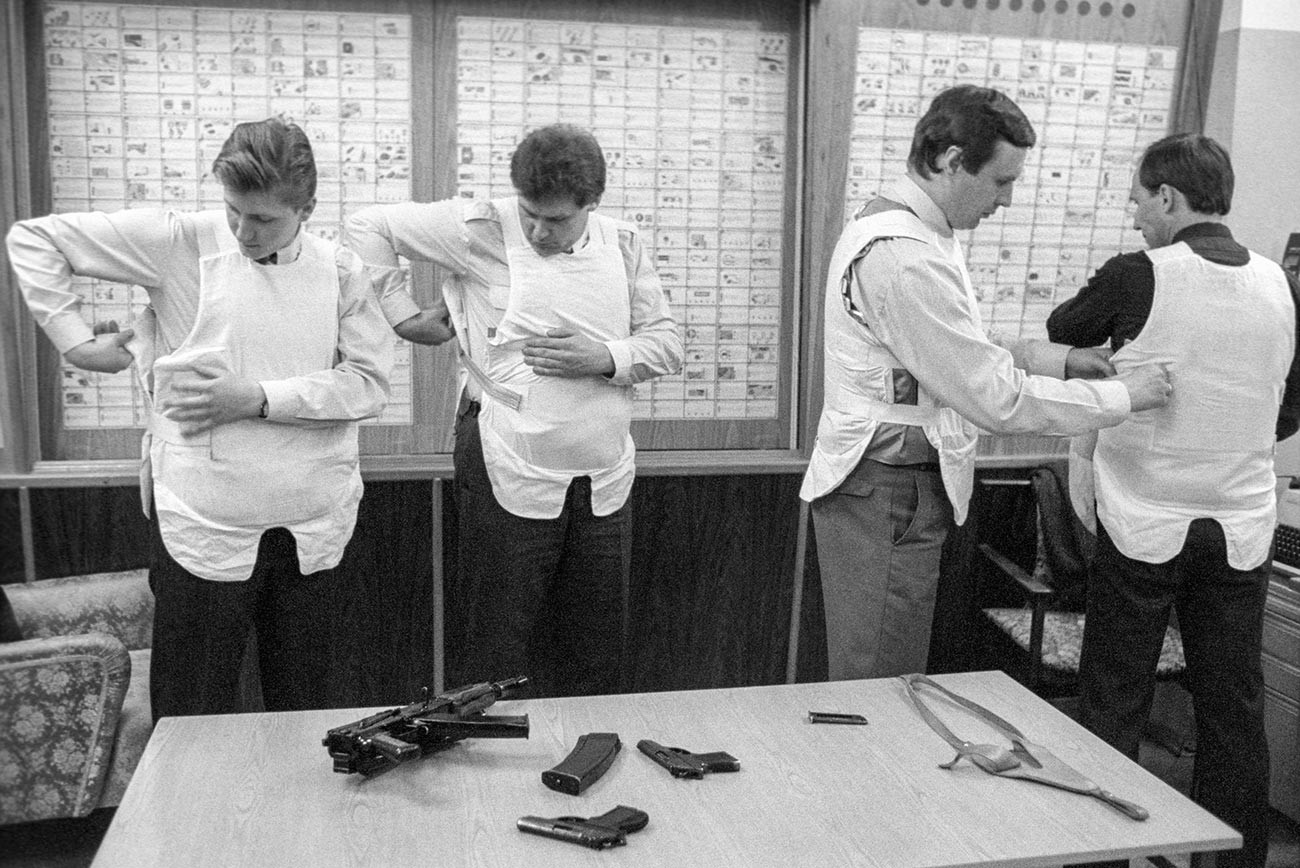

KGB agents get ready for their shift.

Nikolai Malyshev/TASSFormer KGB officer Milekhin said rookies were educated and trained in a very effective manner.

“I have never seen a more motivated and effective training and organization of the service anywhere else. I think [the KGB] was the crown of the ideological work and management of the Soviet Union, the real elite of the country,” said Milekhin.

The KGB’s recruitment was very selective, yet there were instances when the KGB enlisted people against their will.

To fulfill their duties, the KGB staff relied on a wide network of informants. Often, both Soviet and foreign citizens were persuaded — or even conned — into working for the KGB.

Primary recruitment targets for KGB officers who were stationed abroad, especially in the countries of the Western bloc, were either people who had already achieved a certain reputable position — or office — in their country or those who could potentially get there in the future.

A formerly secret KGB manual now published online says the KGB agents must first and foremost have concentrated their recruiting efforts on institutions responsible for controlling foreign policy of the country in question: “Cabinet of ministers, the foreign ministry, leadership centers of political parties, large monopolies, etc.”

KGB agents looked for people disenchanted in their jobs and those who sympathized with the proclaimed goals and founding ideological principles of the Soviet Union.

Ekaterina Mayorova, ‘Miss KGB’ who won a secret beauty contest in 1990.

Nikolai Malyshev/TASSUniversities around the world were also a great breeding ground of clandestine KGB agents, who were recruited and used later, after they had advanced up a career ladder.

Soviet citizens often became inadvertent KGB agents and informants, too.

“Classic recruitment is when a person knows [that he has been recruited]. He takes an alias, often signs a document [saying he concedes to working for the KGB]. He is taught elementary [or] advanced conspiracy techniques: connections, passwords, ciphers and so on. If we take, for example, agents who infiltrate gangs, drug cartels, the terrorist underground and so on, then we need very serious agent training,” said Gennady Gudkov, a former KGB and FSB officer.

History also has known cases where representatives of intelligentsia — writers, artists and athletes — were recruited by the KGB to report on dissident members in their community.

Although KGB recruited informants and agents almost indiscriminately, the committee on state security thoroughly filtered those who wished to be officially employed. A tarnished reputation and/or some physical features could have forever banned a candidate from working in the KGB.

Candidates of unremarkable appearance were preferred, as opposed to those who had certain unusual physical features like nervous ticks, eye defects and strabismus, speech disorders, protruding teeth or large birthmarks, not to mention visible physical disabilities. It was considered that these features could have impaired a candidate’s ability to fulfill his duties, which often required secrecy.

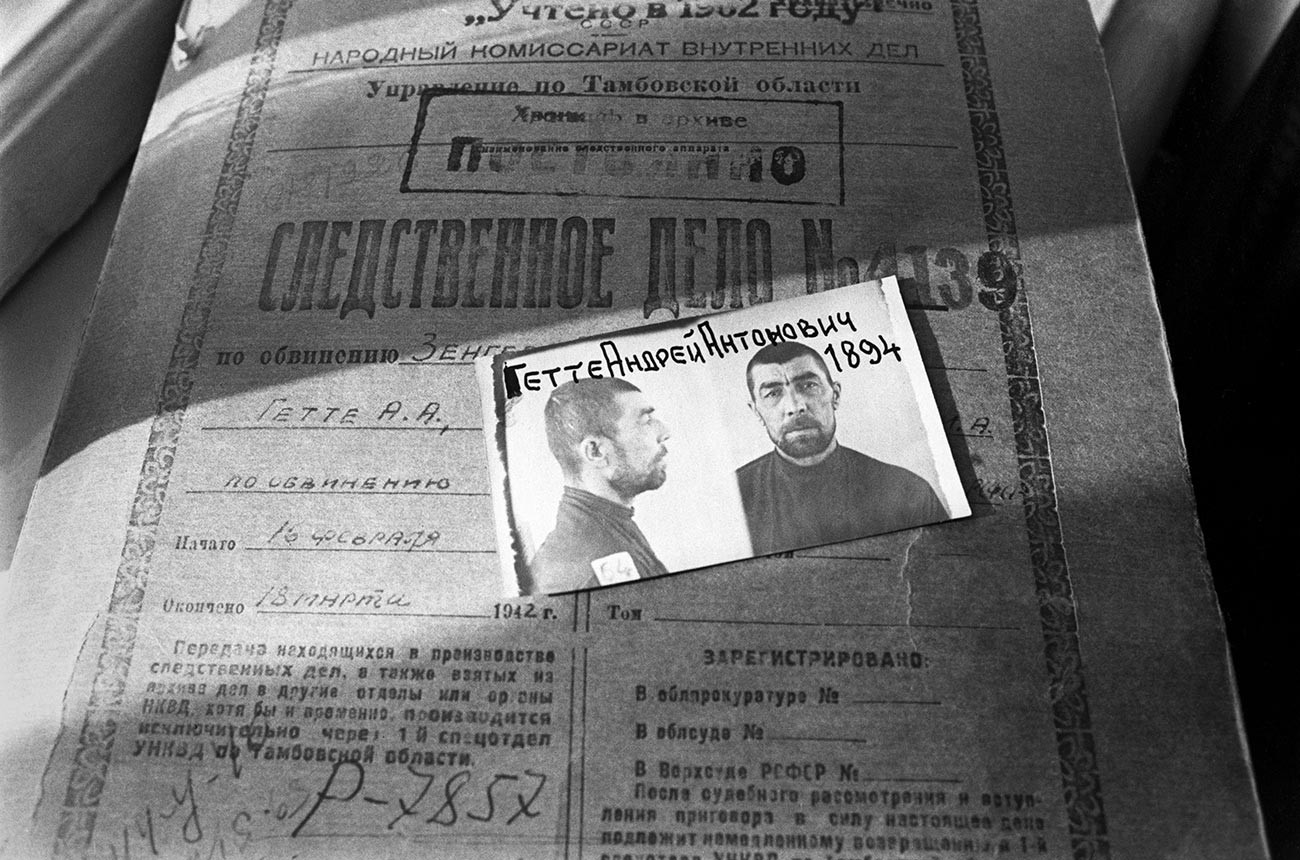

A KGB file on a convict named Andrei Goethe.

Yuri Nabatov/TASSAccording to a former KGB officer turned writer, representatives of certain ethnicities were also unofficially barred from working in the KGB. For example, Jews, Crimean Tatars, Karachais, Kalmyk, Chechens, Ingush, Greeks, Germans, Koreans and Finns were largely avoided by KGB recruiters, as they deemed people of these ethnicities “unreliable” — a fact attesting to ethnic discrimination in the country, which would occasionally lecture the U.S. on racial equality.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox