The idea of space travel was first created by a Russian Orthodox philosopher that was born with the last name ‘Gagarin.’

Portrait of Nikolay Fyodorov by Leonid Pasternak

Leonid PasternakA school teacher and librarian, Nikolay Fyodorov (1829-1903) opposed the idea of property of books and ideas and never published anything during his lifetime. He refused to be photographed and to sit for portraits and two of his depictions had to be made secretly. Most of his teachings he conveyed orally to his disciples and friends. The founder of the Russian cosmism philosophy, Nikolay was a bastard son of Prince Pavel Gagarin (1789-1872). It is considered a coincidence that the first man in space also bore this surname. During his life, Nikolay was known under the surname of his godfather, Fyodorov.

READ MORE: Was Gagarin REALLY the first man in space?

For the latter part of his life, Fyodorov worked in Moscow as a librarian in the Rumyantsev Museum library, which is now the Russian State Library. There, he befriended a lot of intellectuals of his time, including Leo Tolstoy and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the pioneer of Russian astronautics and rocket science.

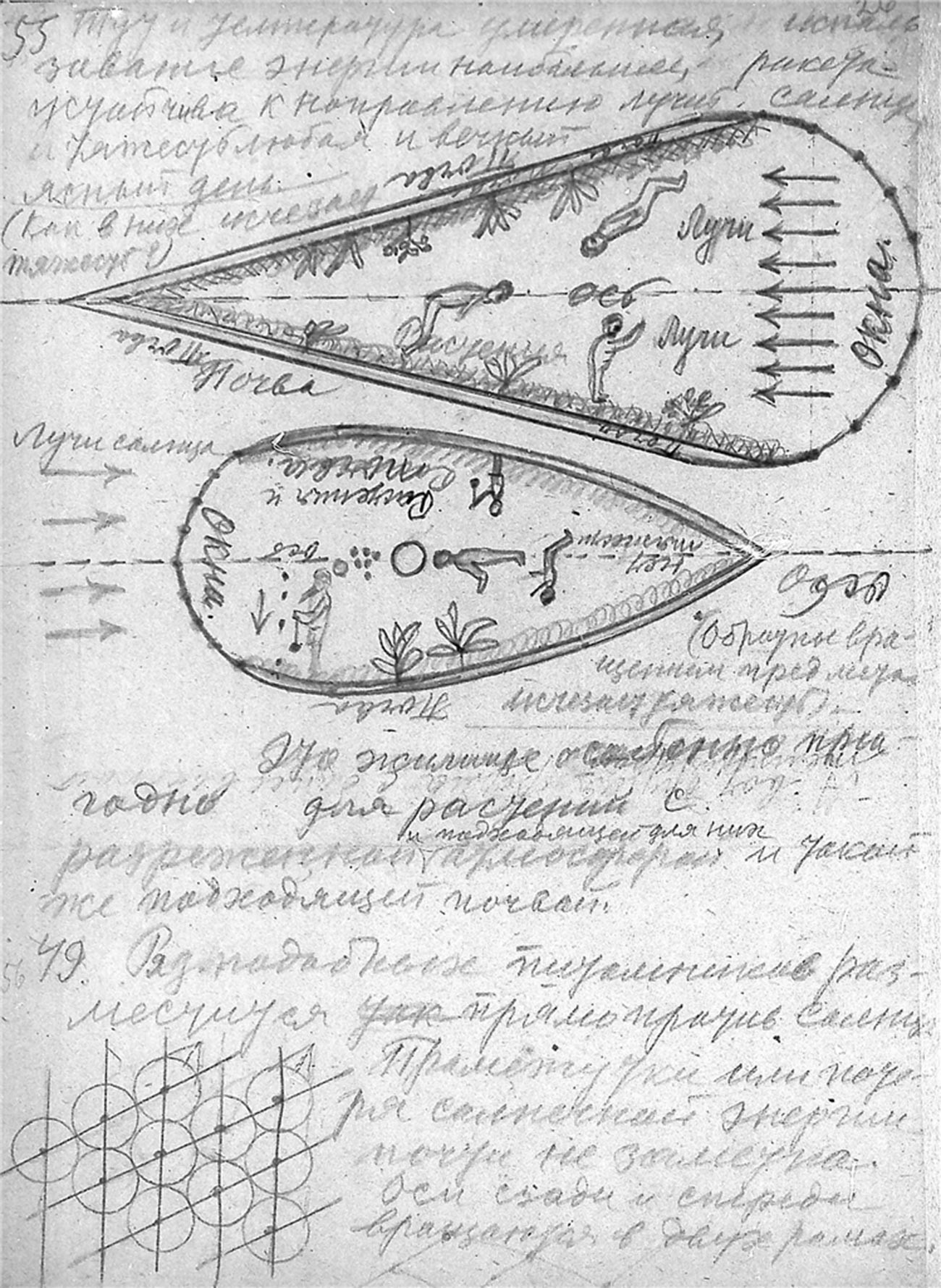

Tsiolkovsky's description and drawing of a spaceship greenhouse

Public domainFyodorov was a strict observant of Russian Orthodox Christianity, but, at the same time, a natural philosopher. His main idea was radical life extension by means of science. He believed that spiritual and scientific development of humanity would lead to the fulfilment of the ultimate Christian idea: the banishment of death and revival of the dead, using the idea of cloning. Fyodorov also believed that space exploration was necessary, because the resources of the Earth are depletable. Later, his followers, who called themselves ‘biocosmists’, propagated the idea of “immediate development of space communications”. The teachings of Fyodorov were taken into account also by Sergey Korolev, the creator of the first Russian space flight.

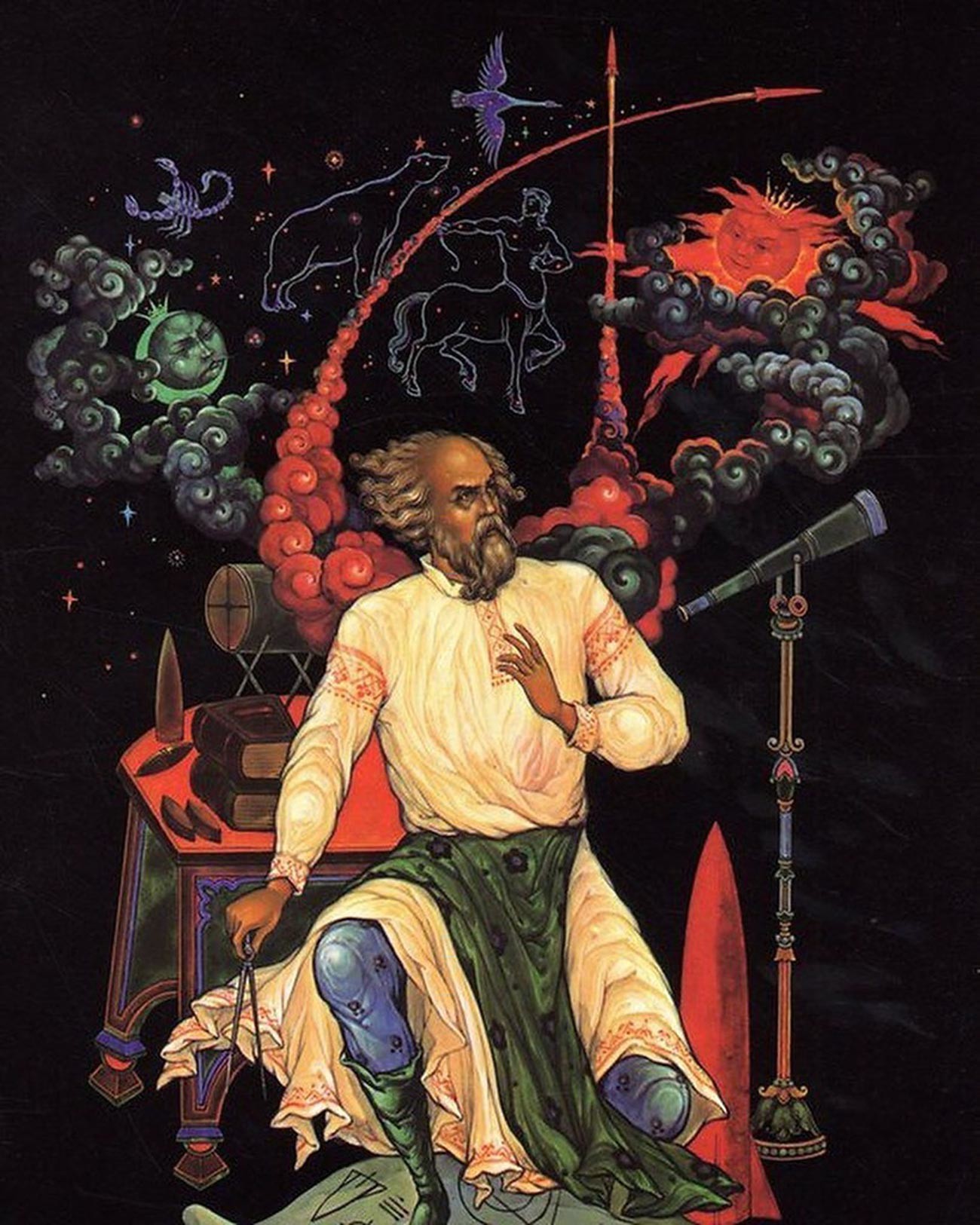

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. From the "Space exploration" series. Palekh Russian traditional miniature painting.

Kaleria Kukuliev, Boris KukulievKonstantin Tsiolkovsky has the full right to be named the ‘Russian Da Vinci’, because, apart from his scientific studies, he was deeply involved in mysticism. Tsiolkovsky stated that he developed the theory of rocketry only as a supplement to philosophical research on the subject.

From the age of 35, he lived and worked in Kaluga, the town that became the center of the Russian theosophical movement. Deaf from an early age due to scarlet fever he suffered as a child, he was very introspective and, for most of his life, continued self-studying. He was at the same time an affectionate and lively soul and claimed to have experienced revealing “visions” twice in his life.

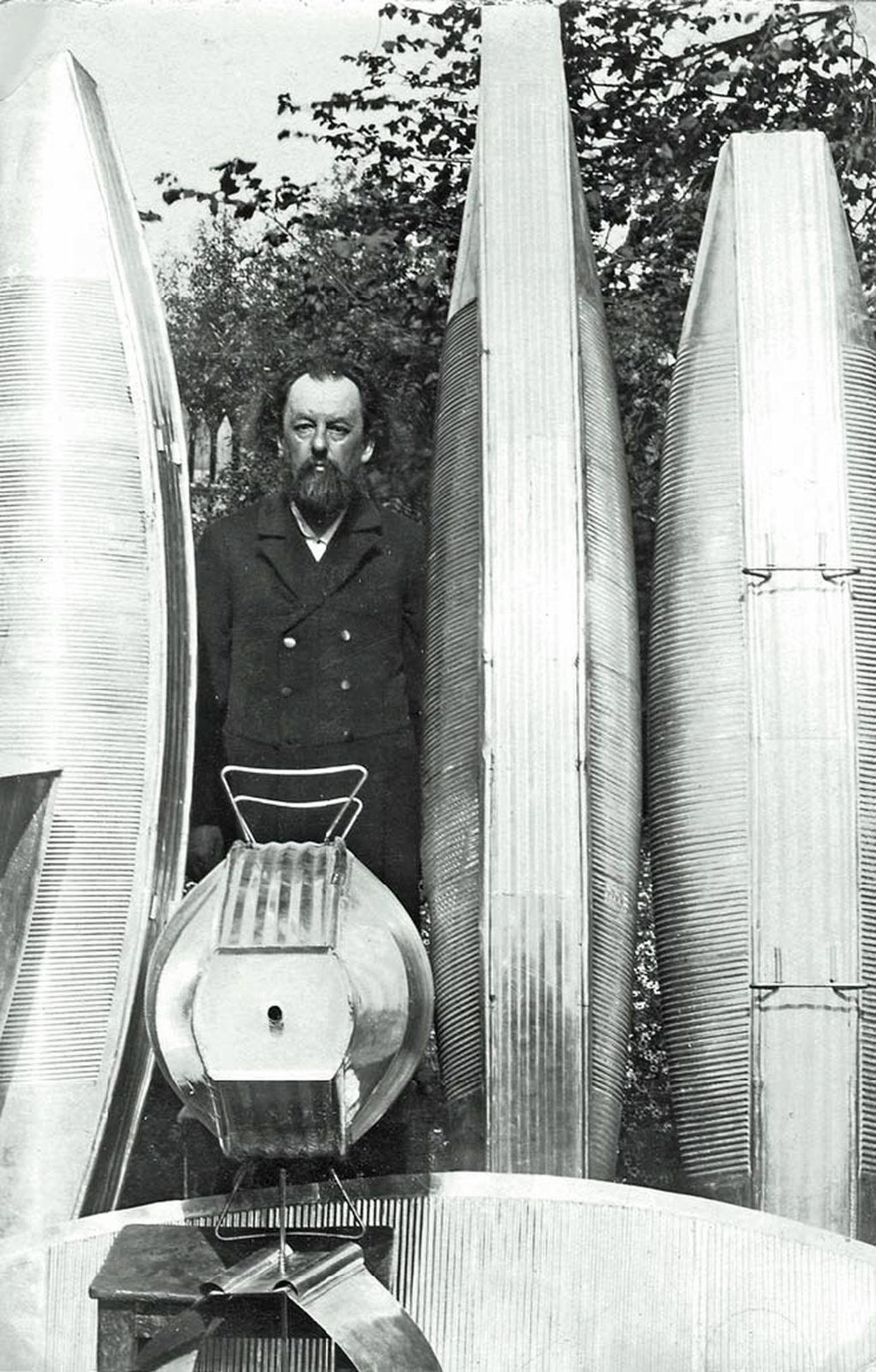

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky with models of his zeppelin

Alexander AssonovREAD MORE: 5 of the most important discoveries by the 'Russian Leonardo da Vinci'

His own philosophy consisted of theism, pantheism and esoterics. He believed in the existence of God, but didn’t associate him with Christ. Developing a theory of space exploration, parallel with Fyodorov’s ideas, Tsiolkovsky famously said: “The earth is the cradle of humanity, but you can’t live in a cradle forever!”

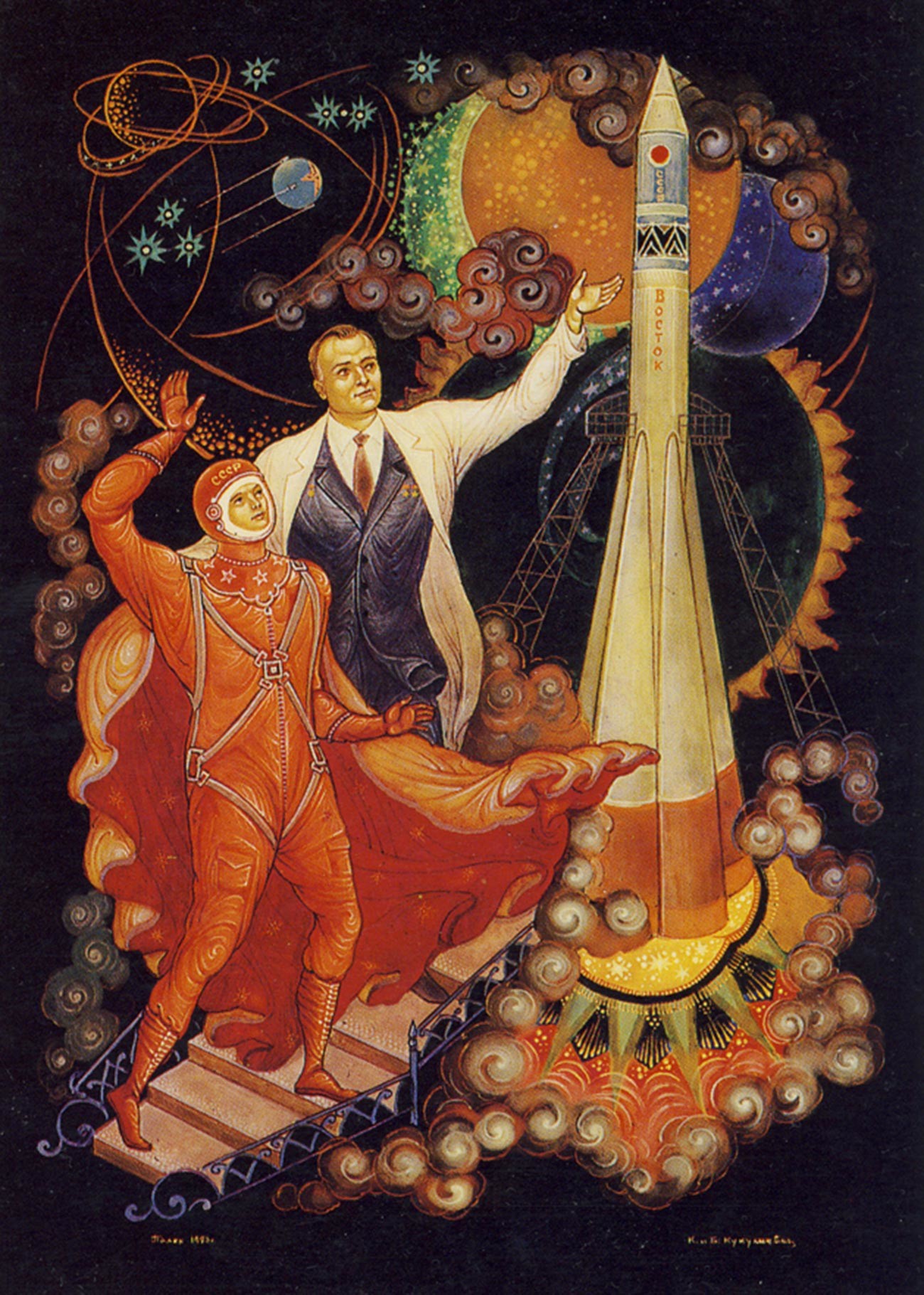

Sergey Korolev sends Yuri Gagrin to space. From the "Space exploration" series. Palekh Russian traditional miniature painting.

Kaleria Kukuliev, Boris KukulievSergey Korolev (1907-1966), the leading rocket engineer and creator of Yuri Gagarin’s space flight, studied the works of both Nikolay Fyodorov and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Their findings and ideas inspired Korolev’s idea to create a rocket-powered aircraft. It is still debated whether Korolev was religious himself, but he was certainly superstitious. It is known that Korolev didn’t put any launches on Mondays and didn’t tolerate women on the launch pad – but Russian cosmonauts have had a lot of other superstitions, as well.

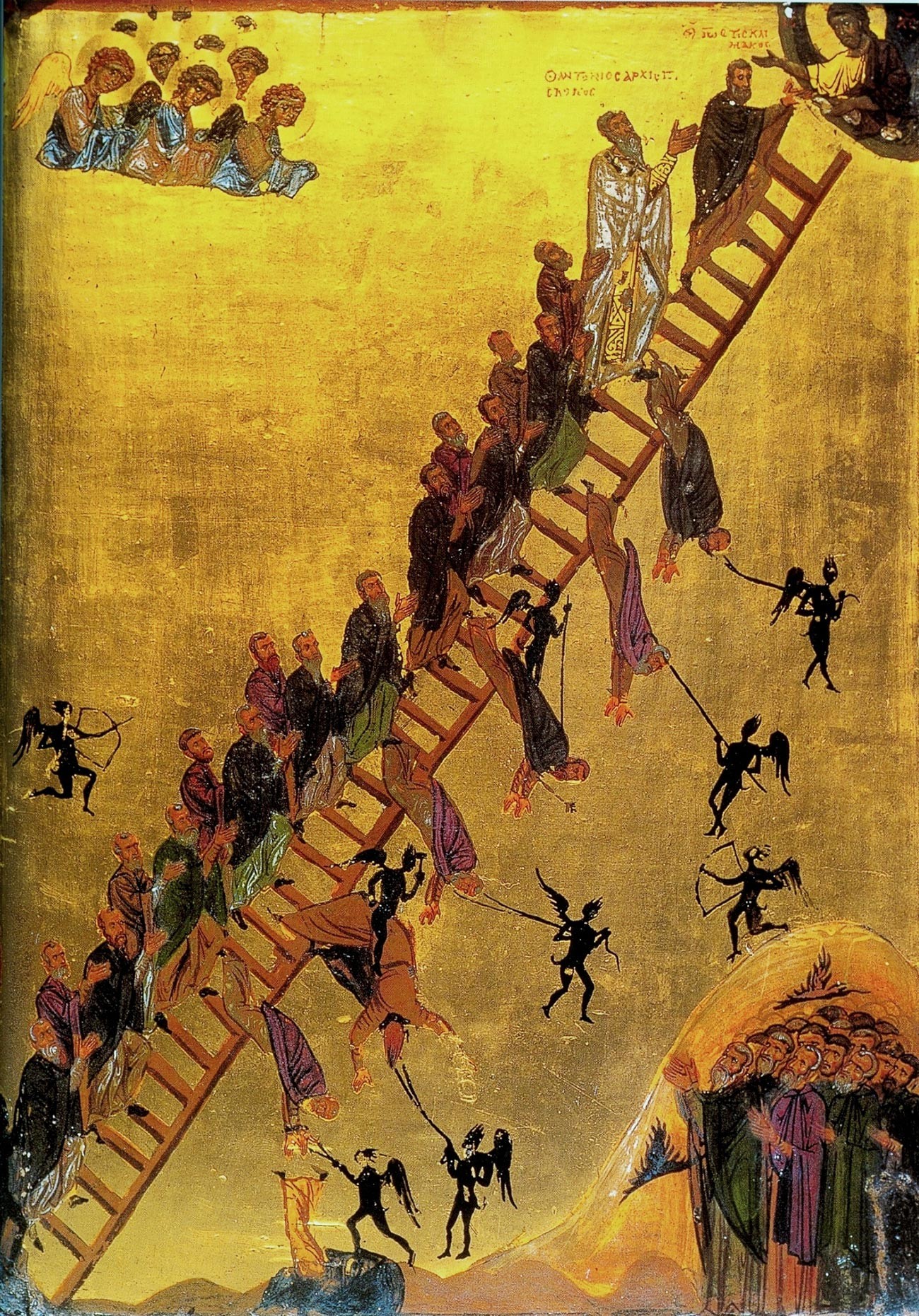

The 12th century Ladder of Divine Ascent icon (Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt) showing monks, led by John Climacus, ascending the ladder to Jesus, at the top right.

Public domainWhat is really remarkable about the first space flight Korolev managed is the amount of “coincidences” in its numerology. First of all, April 12, the day that Gagarin went into space, in the Russian Orthodox church calendar falls on the feast of St. John Climacus (John of the Ladder), the author of The Ladder of Divine Ascent, a monastic text that describes how to raise one’s body and soul to God through monastic obedience. The main metaphor used by St. John is Jacob’s Ladder to Heaven (Genesis, chapter 28). This observation is debated to the present day, with certain Orthodox clerics defending it.

Another coincidence is the total flight time. No doubt it was thoroughly calculated – for example, the next space flight, August 6-7 1961, performed by German Titov on Vostok-2, lasted for exactly 1 day, 1 hour, 11 minutes. Yuri Gagarin on April 12, 1961, famously orbited the Earth in 108 minutes, the number 108 being considered sacred in Hinduism and Buddhism. In these Eastern religions, 108 is a lucky number associated with divine harmony, completion and success.

Consecration of the 'Soyuz-FG' launch vehicle with the Soyuz TMA-20M transport manned spacecraft at the launch complex of the Baikonur cosmodrome.

Sergey Savostyanov/TASSIt is widely known that in 1964, three years after the flight, Yuri Gagarin went to Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius – only for sightseeing. But in the Soviet atheist times, even this led to certain problems and inquiries by Party officials. Later, in post-Soviet times, religious beliefs became a private matter again. And, it turns out, many contemporary Russian cosmonauts are religious.

However, the same can be said about American astronauts. For example, in 1963, Gordon Cooper spoke and recorded a Thanksgiving prayer during his flight. On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1968, the crew of Apollo 8 read from the Book of Genesis as they orbited the Moon and there are other examples.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox