For all appearances, this is true, because in his entire life, Stalin traveled by air only twice, flying 500 km each time: In November 1943, when he flew from Baku to Tehran to meet Roosevelt and Churchill and, in December that year, when he flew back. In all other cases, he preferred land or water transport, regardless of how long it would take. Even to attend the Potsdam Conference in 1945, Stalin didn’t go by air. He just posed for a photo by a set of steps and then went to Germany by train.

His fear of flying was justified, however. In those days, plane crashes happened regularly and both engineers and Stalin’s close associates had lost their lives in them. Until 1933, for example, there was no mandatory annual proficiency test for pilots or devices for blind flying at night or in poor visibility. After one such “ridiculous and horrendous disaster”, Stalin imposed a categorical ban on flying for all members of the Politburo and high-ranking officials. Disobedience was punished by a severe reprimand.

Verdict: True

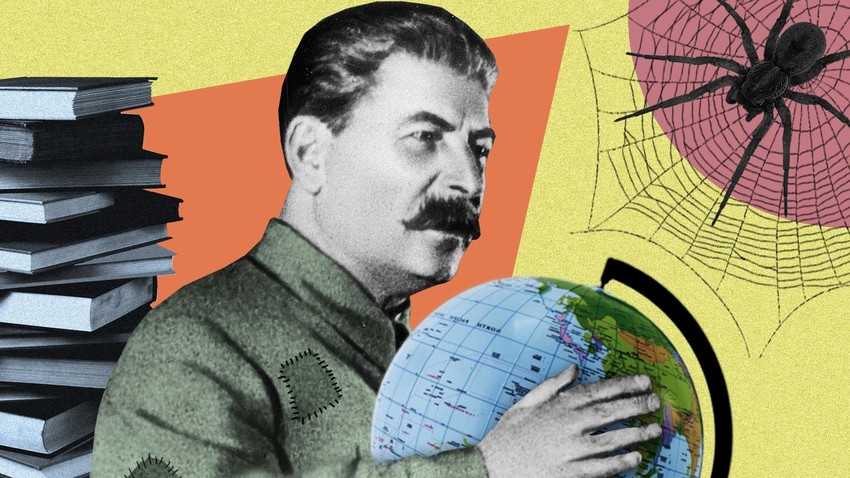

The story that Stalin followed the operational situation during World War II using a globe (because he couldn't read maps) and drew up directives while consulting a globe was first spread by Nikita Khrushchev, who came to power after Stalin. Addressing the 20th Congress in February 1956, he said, according to the transcript of his speech: "We should note that Stalin planned operations using a globe. (Animation in the hall). Yes, comrades, he would take a globe and trace the front line on it." At the congress, apart from denouncing the former leader's cult of personality and his crimes, Khrushchev tried to convince those present that Stalin had been completely ignorant in military matters. The latter, however, was not true. And Stalin's contemporaries attested to this.

Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky wrote that, from the midpoint of the war, Stalin “was the strongest and most colorful figure in the strategic command” and General Sergei Shtemenko had the following to say about the globe: “Behind the table, in the corner [of Stalin’s office], stood a large globe. I must say that I visited the office hundreds of times and I never saw it being used when operational matters were discussed. Claims that frontline operations were decided on the globe hold no water.”

Verdict: False

Stalin was originally from Georgia, so as a child he spoke his native Georgian. Stalin’s mother wanted her son to become a priest and decided to send him to an Orthodox Church religious school. But he was turned down, because he didn’t know Russian. She then persuaded the children of the local priest to teach her son the Russian language.

Stalin in 1894.

Public domain“Until the age of eight, Iosif knew almost no Russian, but in the space of two years he had learned it,” says historian Vladimir Dolmatov. “He graduated from the religious school in Gori in Georgia with a commendation. He was an excellent student during his first years at the Tiflis [now Tbilisi] seminary. But, he was expelled from it for revolutionary activity. In 1924, he started collecting a library. By the end of his life, it contained over 20,000 books. He would read up to 500 pages a day.”

Verdict: True

Iosif Dzhugashvili chose his principal pseudonym - the one under which he entered the history books - when he decided to escape the confines of the regional politics of the Caucasus. Because the name sounds as if it is derived from “stal” (the Russian word for “steel”) and, broadly speaking, because it described perfectly the main characteristic feature for which he was known - his toughness - many believed that he became ‘Stalin’ in a deliberate allusion to the word “steel”. During his lifetime, and for some time after his death, no-one examined the truth of this.

Subsequently, it transpired that it had nothing to do with steel. But beyond that, views diverge. Some researchers believe that ‘Stalin’ was a translation into Russian of part of his surname ‘Dzhuga’ and that it merely denoted a given name. But, the most curious theory is that Stalin gave himself the name in honor of the liberal journalist Evgeny Stalinsky, who published a famous translation of the Georgian narrative poem, ‘The Knight in the Panther’s Skin’, by Shota Rustaveli. Stalin was a fervent admirer of Rustaveli and of this poem in particular, but, for some reason, the best edition of the poem with the Stalinsky translation, published in 1889, was removed from all displays, libraries and bibliographic entries and was not referred to in literary articles. In the view of historian Vilyam Pokhlebkin: “In ordering the suppression of the 1889 publication, Stalin was primarily concerned to ensure that the ‘secret’ of his choice of pseudonym should not be revealed.”

Verdict: False

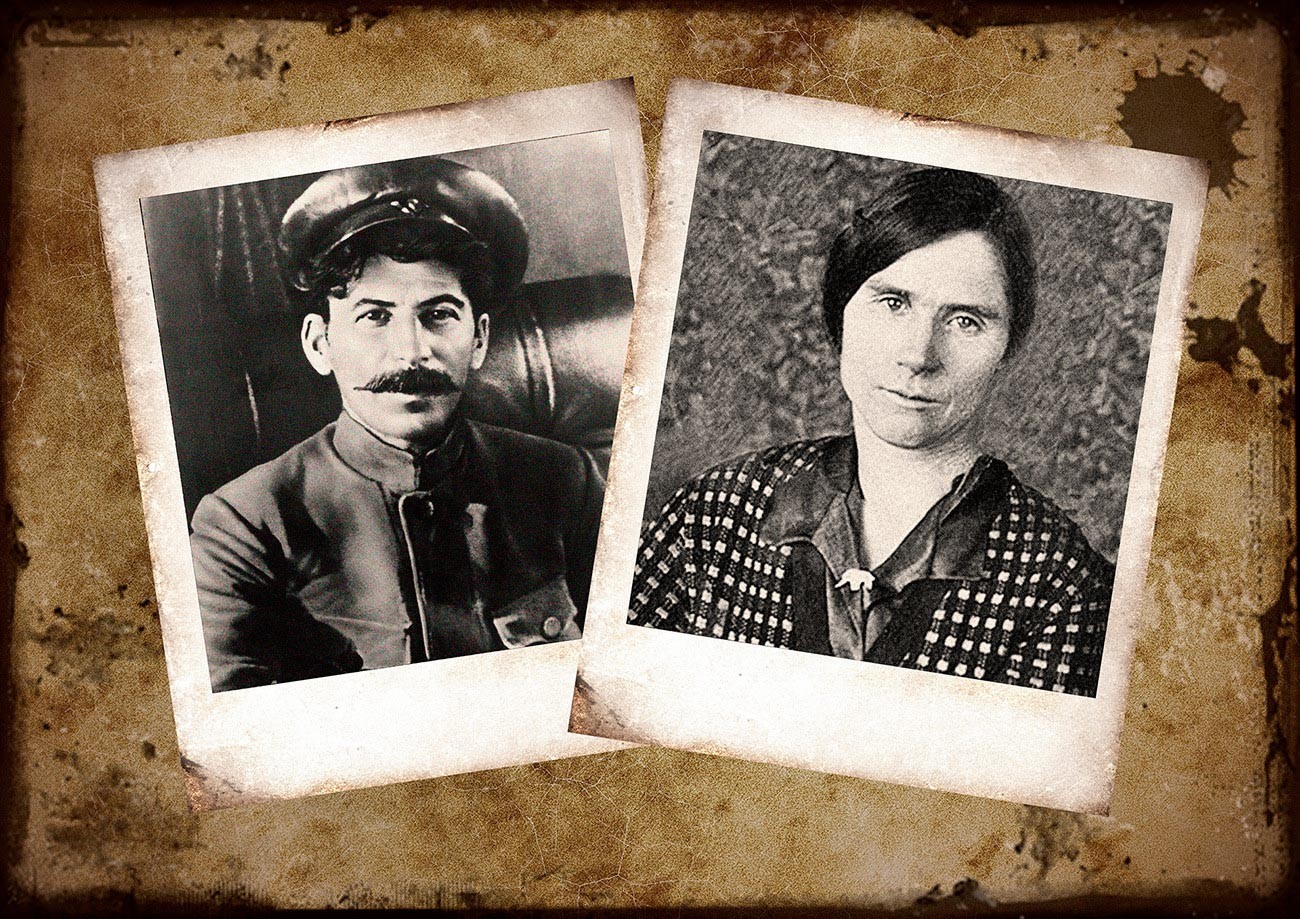

Her name wasLida Pereprygina and, at the time of her romance with the 37-year-old Stalin, she was just 14. From 1914 to 1916, during his Siberian exile, he was billeted in the house where she lived and, in that time, Lida had two children with him. The first one died, while the second was born in April 1917 and was registered as Alexander Dzhugashvili (under Stalin’s real surname). In the village, Stalin got into trouble for corruption of a minor and was forced to promise to marry Lida, but as soon as his period of exile was over, he left for good.

Stalin and Lida Pereprygina

Public domain/Getty ImagesLida Pereprygina subsequently wrote to Stalin asking for his help, but received no reply. Instead, in the 1930s, she was forced to sign a non-disclosure agreement in relation to the “secret of the ancestry” of her son.

Verdict: True

Photo from the private archive of E. Kovalenko.

SputnikThe popular myth that Stalin went around in a single military greatcoat all his life, that he left no savings when he died and that he led an ascetic way of life is completely divorced from reality. In actual fact, he was hugely wealthy, because he had limitless access to all the advantages and privileges of office. Cars, dachas, private doctors, food, an enormous staff at his beck and call in each of his residences - he had everything provided and fully paid for by the state. Around 20 official out-of-town residences were built for him in different parts of the country during the time that he ruled the USSR and they were all fitted with the latest technical refurbishments. Stalin never even carried any spending money with him - he did not need to. At the same time, he also had his official salary (the level of which he set himself) - 10,000 rubles (approximately 3.2 million rubles a month in today’s money, or $43,500), as well as receiving huge royalties for his writings and translations of his works into foreign languages.

Verdict: False

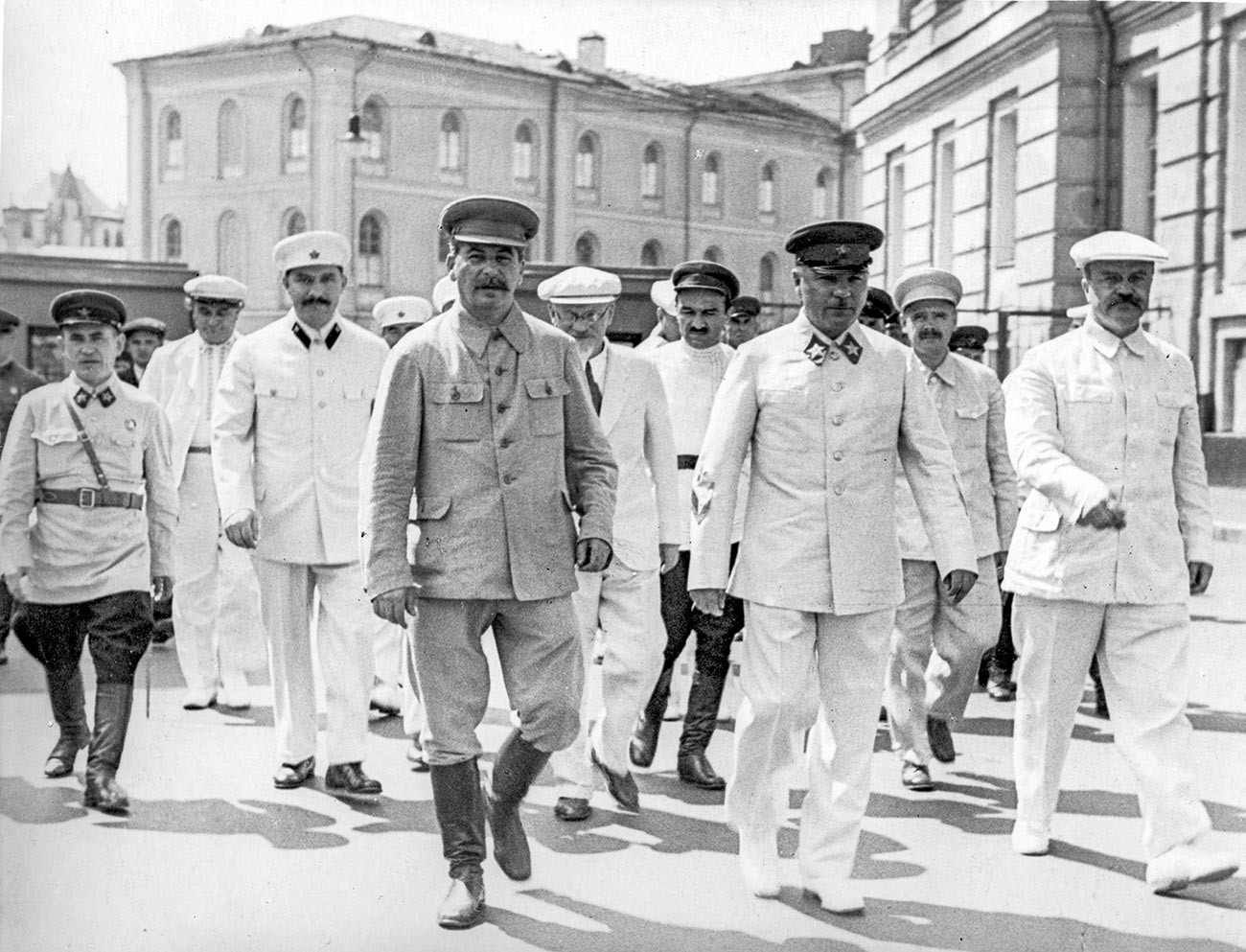

Stalin was guarded at different times by between several dozen and tens of thousands of men (as during his trip to Potsdam in summer 1945). According to the memoirs of his bodyguard Vladimir Vasilyev, even when formal sessions were being held in the Bolshoi Theater, in addition to guards around the building, at entrances and exits and backstage, the hall was veritably flooded with members of the security services dressed in civilian clothes. There was one agent for every three invited guests. He trusted no-one, even his personal cooks, and, at receptions, he always tried the food after someone else had tried it first.

In the post-war years, the protection of Blizhnyaya, Stalin’s dacha near the village of Volynskoye, could only be compared to Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair: “The only road leading to the dacha was guarded by police patrols day and night. They were a sturdy, broad-shouldered lot, each with the rank of captain or major, even though they wore petty officer shoulder marks. The woods surrounding the dacha had entanglements of razor wire. If someone had succeeded in finding a way through, I would not have envied them. They would have been assailed by the Alsatian dogs that ran loose along the wire stretched between posts,” Vasilyev wrote.

“The next line of defence was a series of light beam devices brought back from Germany. Two beams installed in parallel securely guarded the ‘perimeter’. If so much as a hare leapt into their path, a light would be illuminated on the duty officer’s control panel and tell him what sector the ‘intruder’ was in. Then there was a five-meter-high fence of really thick boards. This had windows in the form of firing slits, next to which were sentry posts for the armed guards. Next was a second fence, this time a little lower. Naval signalling lamps were installed between the two. And keeping watch next to the house itself were the personal guard - members of the ‘9th Directorate’,” Vasilyev recalled.

Verdict: True

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox