Parade in Red Square on the birthday of the All-Union Pioneer Organization

D. Chernov/SputnikAfter the 1917 Revolution, the new government set a course for optimizing living conditions. There was no more private property, the state presided over all real estate. Large apartments, especially in Moscow and St. Petersburg, were transformed into communal living quarters - or kommunalkas. Families would only receive one room (large ones were split into smaller ones) for all their members and their belongings. The rest of the space was for common use.

Read more:5 bizarre rules for Soviet-era communal living

However, common bathrooms, toilets and halls were more than just a forced compromise in a gigantic country with limited living arrangements. The issue was about new accommodation for workers old and new - for the Soviet person as a whole, who never places personal needs above the needs of the many.

Communal apartments exist to this day and, what’s more, are still in fashion as the most affordable mode of living.

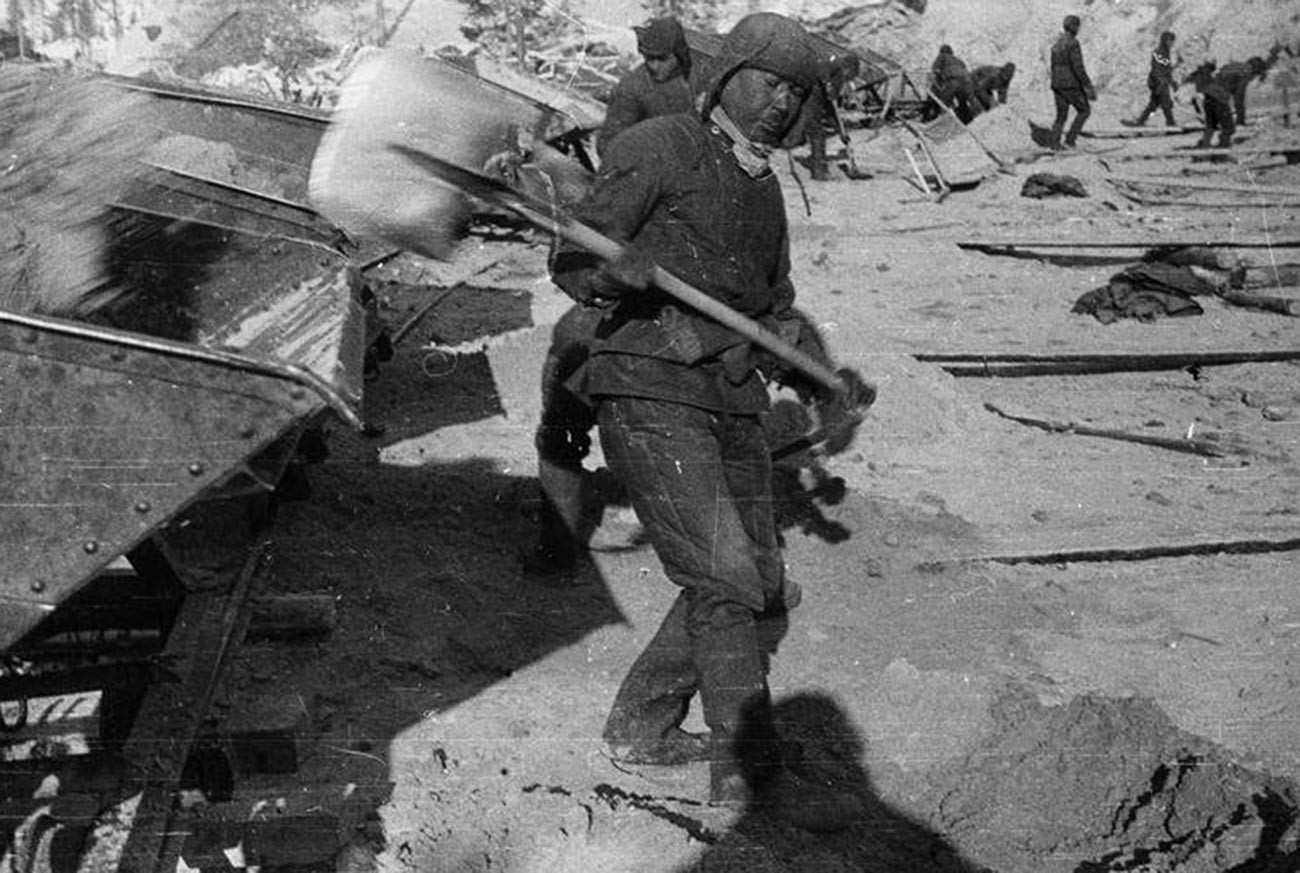

Prisoners at the construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal

Alexander Rodchenko / MAMM / MDF / russiainphoto.ruThe Soviets constantly grew their prisoner ranks, using them as manual labor at digs, mines, fells and for railway construction. These labor camps steadily increased in number, in line with the increasing severity of repressive measures, so it was eventually decided to unify them into a system. And so, the GULAG was born - short for “glavnoe upravlenie lageryami” (“Headquarters of Camps”).

Throughout its history, the GULAG penitentiary system produced over 30,000 prisoner camps. They differed in their pursuits, with some working toward economic goals and others operating a more production-based regime. The living conditions were different everywhere as a result. However, the GULAG system was structured in such a way that prisoners could not forge any lasting contacts - no one would be held in one facility for too long and were rotated on a shift basis.

According to the GULAG Historical Museum, more than 20 million prisoners went through the system in the 1920s-1950s. Over one million of them died as a result.

“Pious” communists were raised to be that way since infancy. They would then become pionery - “pioneers”. The V.I. Lenin All Soviet Pioneer Organization accepted children aged 9-14. They would recite their pledge of allegiance and become inseparable from their red tie, which they had to have on at all times as a marker of membership.

The first pioneers appeared back in 1922 and membership conditions were stricter for a while, as it was an elite institution. That aspect of life evaporated shortly and membership in the Pioneers became - if not mandatory, then at the very least, very desirable for every Soviet child. Collecting scrap metal and paper, and performing all manner of other community service, as well as participation in various military-sports events and an excellent academic record - that is what was expected of a pioneer. The group had their own salute: the right hand would be raised slightly higher than the head, to indicate that the pioneer valued the common good above personal gain. The call of “Be ready!” would be responded to with “Always ready!” The specifics of what that readiness was for was only known to the Communist Party - the pioneer was expected simply to blindly follow.

Soviet car "VAZ 2101".

Dmitry Donskoy/SputnikThe VAZ 2101 was the most popular mass-produced Soivet car, known affectionately as the kopeika - or the kopek, the minor currency of Russia and the former USSR. It was also the most affordable car. For many, the kopeika was the first (and only) they’d ever owned. It still elicits nostalgia in a great number of Russians.

The first six kopeikas rolled off the conveyor belt in 1970. Soviet constructors used the Italian-made FIAT-124 as a prototype, adapting it to Russian roads and requirements. The kopeika had a number of versions. There was the race mod, then a mod for the police, a station wagon - and even an electric car!

Academician Andrey Sakharov

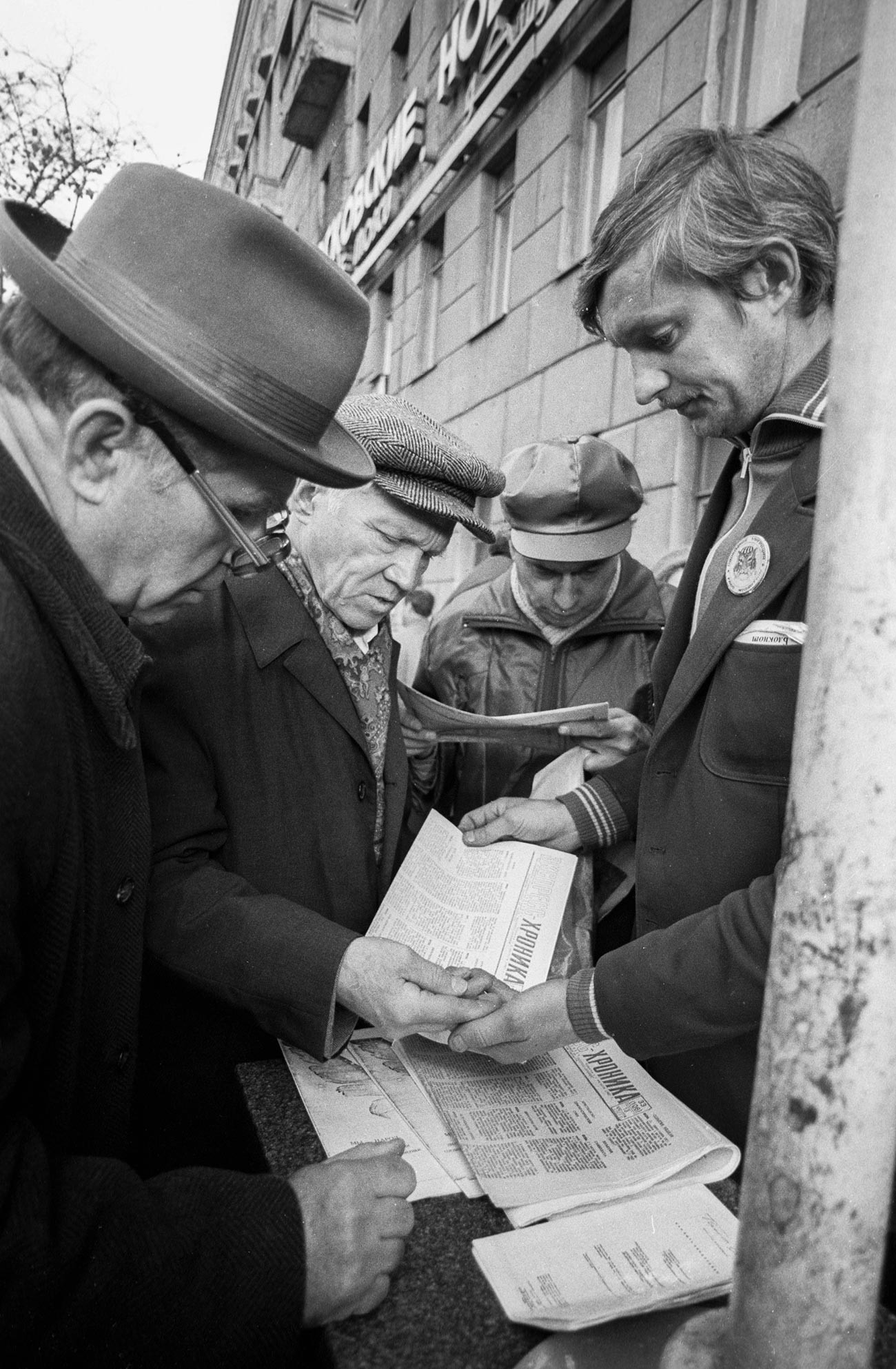

Vladimir Fedorenko/SputnikThe word comes from the Latin word dissidence (“to disagree”, “to stand apart”). The name was first given to Soviet opposition in the 1960s, which used nonviolent means to demand that the Soviet rule observed the laws enshrined in the Constitution. The dissidents fought for freedom of speech, the freedom to gather and free movement, fair elections, the release of political prisoners and basic human rights in general. Their aim wasn’t to seize power - there wasn’t even a proposed plan of reforming it if they had. In the 1960s-1980s, the number of people that aroused the KGB’s interest and were ‘invited for a chat’ stood at half a million people. But that’s only the official statistic. The actual number is unknown, since most of these people weren’t politically active and merely had banned literature in their possession, for instance. There were also those who self-published.

The naysayers were persecuted, given prison sentences, sometimes sent to GULAG (see pt. 2) labor camps - or even placed in psychiatric wards, as well as stripped of citizenship and exiled to other countries. The movement fizzled out by the late 1980s, as the country was taking its first steps toward democratic reform.

This word was used to imply the above-mentioned self-published literature, brochures and audio tapes. Samizdat (from the words “self-published”) was the only way to circumvent censorship. Sometimes, it was a book that was stuck in pre-publishing limbo, with the author wanting to publish it before the censors were finished with it. People also self-published Bibles - not that the Bible was illegal, but demand greatly exceeded supply. Samizdat used to be written using typewriters, most often in state typographies, behind closed doors - which was very dangerous, given that there was a paper count. Just one copy of a self-published book could make the rounds hundreds of times. This is how Valery Grossman’s book ‘It’s All Flowing’ was read by 200 people (the exact number is known, since these were all people Grossman knew personally).

Brutalism is, perhaps, the least unambiguous of all modernist architectural styles: Europe seems to gradually be targeting it for demolition, due to associations with communism and just the overall ‘brutal’ look. But even modern Russia still finds use for these metal and concrete monsters.

Brutalism had many adepts in the USSR. A real explosion of the style occurred all over the country in the 1950s-1970s. The structures were especially convenient as administrative buildings, as they allowed for increased segmentation. The block forms and simple textures were ideal for the period’s needs, with gigantism also a notable highlight of the Soviet construction style. Graphical representations of various scientific and technical achievements would often adorn the facades. One only has to look at the The State Scientific Center for Robotics in St. Petersburg, with the name later amended to also include “Technical Cybernetics”.

A team of workers at the construction of the BAM.

Igor Mikhalev/SputnikThe Baikal-Amur Mainline - or BAM - can rightfully be considered the embodiment of the grandeur of Soviet mega-construction aspirations. Projects targeting complex infrastructural needs would often last years and were ideologically bolstered and considered the pride and achievement of the socialist-communist regime. Sadly, completing those projects would often come at a tragic cost. And BAM was an absolute record holder in that regard!

In 1932, the Party decided to lay a total of 4,287 km of track through 11 rivers and various unreachable territories, all the way to Russia’s Far East. Incredibly, the government’s timeline for the project was a mere 3.5 years. The unrealistic plan fell through and, as a result, work was only completed decades later, in 1989, just two years before the fall of the USSR.

The initial construction was being done by prison inmates, who had to work in subhuman conditions, sleeping under open skies for a year and a half, with daily food rations totaling just 400 grams of bread. Whenever deaths occurred, new inmates would arrive. Later on, the entire country was put to work completing BAM, which became “the communist dream” - for dream’s sake. As it turned out, when it was launched in the early 2000s, the railroad was underused, only incurring losses as a result.

The cult of Vladimir Lenin was phenomenal in scope. Every Soviet city had a prospekt (a long street), a square or a collective farming union named after the father of the Revolution. And, of course, there were the monuments. By 1991, the USSR had 14,290 of them.

In art, this type of worship was dubbed ‘Leniniana’. Between 1910-1980, this form of expression contained a multitude of different images of the leader - the Lenin Museum alone contains 470 paintings of him. There were strict rules that every sculpture and artwork had to abide by. And it was only in the era of social art and postmodernism that people began straying outside of those boundaries.

Siberians lining up outside a store

Peter Turnley/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images/Getty ImagesThe Soviet economy, as many other spheres of life, was regulated by the government. It presided over the type, quantity and price of produce to be distributed across the country. The decisions were made in Moscow, with the government plan often resulting in a lack of even the most basic necessities (such as there being no toilet paper left in a whole city). Elena Osokina, a historian of the Soviet period, writes: “The reproduction and worsening of the deficit was baked into the recipe of centralized distribution, which created interruptions and crises, and made the card system a chronic staple.”

Deficits (including a deficit of information) was indeed a chronic disease of the Soviet period. Everything was administered in doses. A situation materialized, whereby people as a whole had money, but had nothing to spend it on. In the 1970s-1980s, practically everything was in a deficit: there were long lines for everything from pantyhose to condensed milk to shoes, children’s clothes and instant coffee.

These realities shaped the lifestyle and mindset of the Soviet citizen, who would always try to stock up on items and spent entire weekends and after-work hours standing in lines. This mode of living affected even public transportation. For instance, there were “baloney trains”, set up by authorities for populations living on the outskirts, so they could travel to bigger cities and line up for produce before a celebration or a state holiday (mostly for New Year).

This phenomenon dates back to the 1970s-1980s, having emerged during the period of the deficit and a slightly opened Iron Curtain. It implies black market buying and reselling of deficit goods brought from abroad. The majority of the buyers of such goods in the early stages were fashionistas, who were in love with the American lifestyle and sought to get their hands on all manner of foreign goods at a time when the population couldn’t have dreamed of international travel. With time, demand grew to encompass other segments of the population, including school children, seeking to make an impression on their classmates. The prices were astronomical: foreign brand jeans could cost up to 150 rubles, which amounted to an average monthly salary in the 1980s.

The business of reselling could land you an eight-year prison sentence. A piece of bubble gum, a vinyl record, jeans and cigarettes - it didn’t matter what the goods in question were. Still, there were people willing to take the risks. Most of the time, it was thanks to having contact with foreigners: diplomats, taxi drivers, tour guides and so on. It was only at the dawn of the 1990s that the practice began to wane, when Soviet isolationism came to an end and people could travel the world.

Read more:Wanted: dollars, cigs and jeans. The secret world of Soviet ‘fartsa’ (PICS)

Working in a Volgograd Tractor Factory

Dean Conger/Corbis/Getty Images/Getty ImagesSo-called ‘five-year plans’ to bolster the economy were a priority for the country. They implied the following projects: construction of an X number of roads, factories and hydroelectric plants, increasing oil and coal production by 50 percent and so on. The plans were simultaneously a form of economic planning and socialist competition - the first pyatiletki were actually four years. One of the mottos used was “Achieve a five-year plan in four years!” calling for the country to work hard and complete the objectives ahead of time. And, for a time, it worked: By the end of the third pyatiletka, the predominantly agrarian country had become an industrial power.

However, since the late 1950s, the five-year pyatiletkas became semiletkas - or ‘seven-year plans’. The post-war development just couldn’t catch up to what was on paper. But even the seven-year plans began to fail with time. Instead of the planned 70 percent economic growth, it would amount to just 15. Next came the eight-year plans. In the end, the only plans considered to have been a success were the first three pyatiletkas.

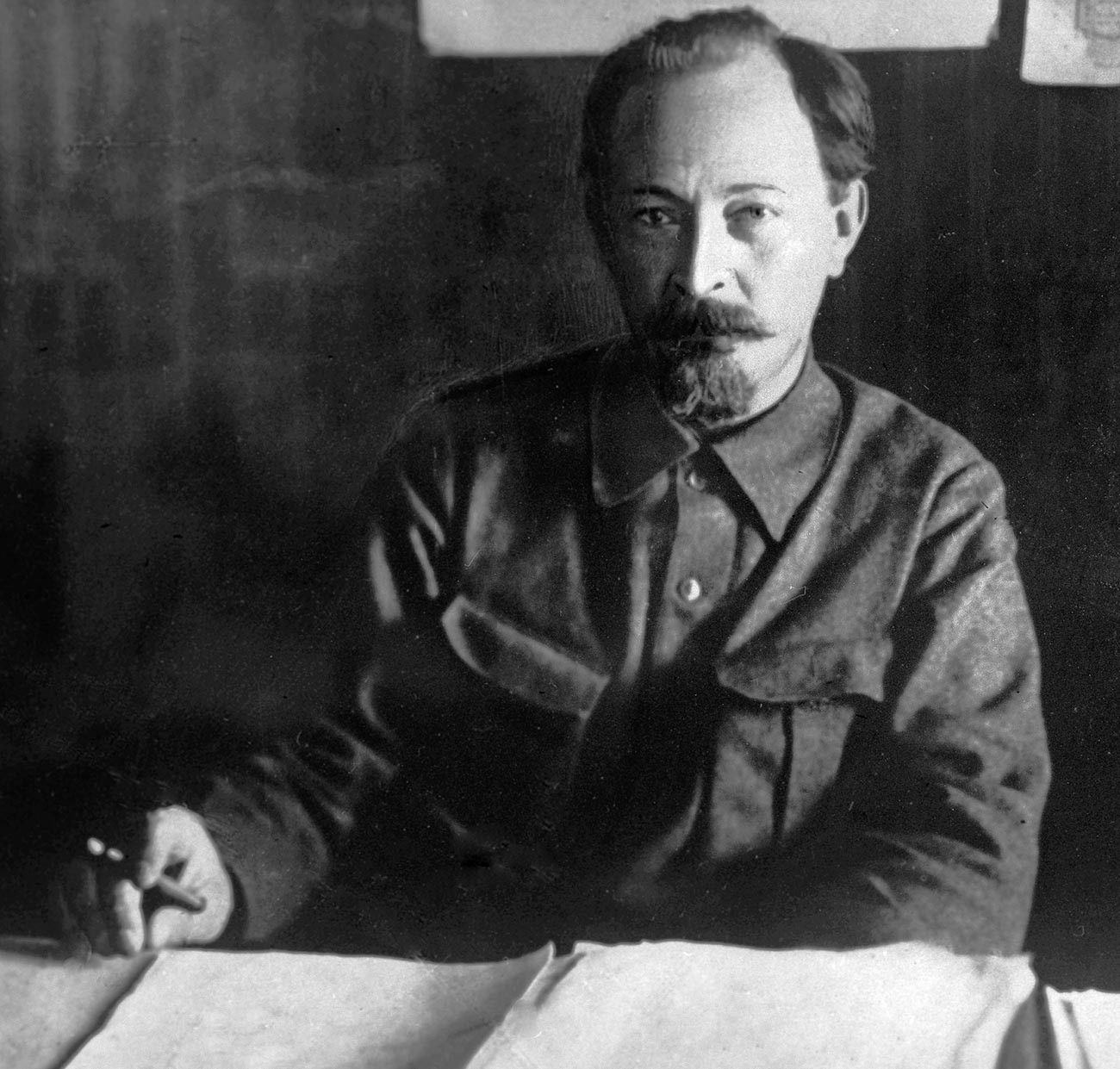

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky at his desk.

SputnikThe word chekist comes from the abbreviation of the name of the first Soviet security agency - the VChK (“the all-Russian emergency commission”). It consisted of loyal bolsheviks, “revolution’s gendermes”, who guarded the interests of the Party and fought the counter-revolution. The body appeared in 1917 and, within three years, the chekists already had power to shoot on sight any “hostile agents, black market speculators, goons and hoodlums, counter-revolutionary propagandists and agitators and German spies”.

Soon, these “defenders of ideology” concentrated in their hands all of the government’s powers of repression, having been given the ability to dispense justice as they saw fit, without a trial. Various sources put the number of those executed at between 50,000 and 140,000 - and that’s just the official ones. Throughout the history of the Soviet regime, the organization changed its name multiple times (VChK, GPU, OGPU, NKVD, NKGB, MVD, MGB and KGB), but the word chekist remained unchanged, and continues to man any member of the Russian security service. Today, they belong to the FSB.

The Soviets tried to create a special type of human being - the “Soviet man”, which implied a number of moral and physical traits. Peredovik was one of the versions of such an ideal. The name was given to anyone who regularly outperformed at work, exceeding their quota. This voluntary sacrifice in the name of industrialization was valued far more than working conditions or the health of one individual. They were practically made a hero. Peredoviks took part in so-called socialist contests as they raced to complete and exceed their quotas to advance their position - something they’d be rewarded for with a trip to a medical spa or move up in line for receiving an apartment from the state. This attitude was referred to as “loyalty to the Soviet state”.

What was valued even greater - but never rewarded, as it was considered to be a quality that every Soviet citizen must possess - was voluntary, unpaid work.

Residents of the city at the Lenin communist subbotnik.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/SputnikOne of the forms of labor that was unpaid was (and still is sometimes) the Subbotnik - from the Russian word for ‘Saturday’, which is when they usually happened: every Soviet citizen would engage in cleanup work in spring or fall, taking care of the area around their building, school or university.

Read more:What was the Soviet 'subbotnik'? (PHOTOS)

According to communist ideology, a decent man would not avoid this form of collective unpaid labor - just as they wouldn’t avoid the May 1 parade. Anyone who didn’t show up was swiftly branded as lazy and publicly derided for it. If the Party called on acts of labor heroism, one answered the call.

Collectivization was another facet of Soviet utopianism - an idea that millions of people can work together in a state of bliss and agreement and with a common goal for the growth of a young country. Starting in 1927, collectivization abolished private property and individual peasant holdings; it set up collective farms - or kolkhozes, which were unions of state farms. Kolkhoz workers didn’t have a salary to speak of and lived only off of what their collective farm produced - strictly enough for their families, not more. Wealthy peasants, known as kulaks, were stripped of their properties and evicted.

By 1932, the entire country counted more than 200,000 such kolkhozes. The passport system was introduced the same year, but kolkhozniks weren’t included in the reform, which deprived them of the opportunity to relocate to a city. For all intents and purposes, kollektivizatsiya was a mutated form of serfdom, chaining millions of people to a plot of land.

In the period of mass repressions, starting in the early 1930s, thousands of scientists, engineers and constructors found themselves behind bars. They didn’t do their time in general pop, however - there were specialized sections of the GULAG system for them. They were referred to as sharashki, places that doubled as prison institutions for highly skilled labor (for instance, the atomic bomb was produced in such a place). The conditions there were more merciful than in labor camps somewhere in the taiga, largely due to the fact that there was no hard labor. Amazingly, you could earn your freedom by successfully completing a government project. This opened the door for a full pardon and rehabilitation.

Meanwhile, getting into one of those institutions required almost no effort. Fighter pilot Mikhail Gromov recalled: “Arrests would take place because aircraft industry designers would write reports on each other - each one praised their own work and tried to sink his rival’s.” Oftentimes, these specialist brigades would accomplish greater things locked up than their free comrades - and Soviet rule understood this: there was simply greater motivation when your release was on the line.

Read more:How convicts designed the best Soviet weapons from prison (PHOTOS)

Notable sharashka inmates included Sergey Korolev - the father of Soviet cosmonautics, responsible for Yury Gagarin’s 1961 space flight; Vladimir Petlyakov, the constructor of the Pe-2, the most mass-produced Soviet bomber in history; writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - who was educated as a mathematician and many others, who are known today as the pride of Soviet science.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox