Soviet POWs in Riga in July 1941.

ullstein bild via Getty ImagesAt 4 a.m. on June 22, 1941, the forces of Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union as part of Operation Barbarossa, advancing in the direction of the country’s three main cities: Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev. Despite fierce resistance and continual counterattacks by the Red Army, the enemy made rapid progress deep into the USSR. Having inflicted a powerful blow to Soviet airfields, the Luftwaffe ensured air supremacy from the first days of the war.

“The total unexpectedness of our offensive was evidenced by the fact that units were caught unawares in their barracks, planes were standing on the airfields covered with tarpaulin and the forward elements attacked by our troops without warning had to ask their command for instructions…” Franz Halder, chief of staff of the German Army High Command, wrote in his diary.

German troops in the USSR in June 1941.

Public DomainOn June 24, German forces took Vilnius, on June 28, Minsk and, on July 1, Riga. After the encirclement and defeat of the main forces of the Soviet Western Front in the Battle of Białystok-Minsk (more than 420,000 of 625,000 soldiers were killed, wounded or taken prisoner), its commander, Army General Dmitry Pavlov, his chief of staff, Major-General Vladimir Klimovskikh, and several other commanders were arrested and executed.

German troops in the Soviet Union in June 1941.

BundesarchivIn Ukraine, the forces of five mechanized corps of the Soviet Southwestern Front clashed in fierce battles with the German 1st Panzer Group in the area of Brody-Lutsk-Rovno. The overwhelming numerical advantage of the Red Army in tanks (2,500 against 800) was negated by the lack of proper radio communications, poor organization of reconnaissance, flawed coordination of actions by formations and tactical errors by commanders.

As a result, in one of the largest tank battles in history, the Soviet troops suffered a heavy defeat: The mechanized corps lost from 70 to 90 percent of their tanks. In actual fact, many of them could have been repaired, but were abandoned, because of the general retreat. At the same time, the Germans didn’t emerge from the battle unscathed, either: The pace of their offensive slowed and they failed then to encircle and defeat the forces of the Southwestern Front.

Burning T-34 during the Battle of Brody-Lutsk-Rovno.

BundesarchivNot in all sectors of the Soviet-German front did the Wehrmacht manage to conduct its “lightning war” effectively - far from it. In the Arctic, the enemy advanced only a few tens of kilometers into Soviet territory, failing to capture the major Soviet seaport of Murmansk.

“We were promised we would take Kandalaksha in twelve days and reach the White Sea, but, so far, we have not succeeded, although six months have already passed. The mood of the soldiers is depressed - they did not expect such dogged resistance from the Russians,” a captured German corporal lamented in January 1942.

Soviet troops in the Arctic.

Evgeny Khaldey/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruFor two months - from July 10 to September 10 - a large-scale bloody battle took place near Smolensk, as a result of which the Red Army had more than 750,000 men killed, wounded, missing or taken prisoner. The combat effectiveness of the Soviet troops covering the German line of advance towards Moscow was severely undermined.

At the same time, contrary to its original plans, the Wehrmacht itself, having suffered sizable losses of 100,000 men, was held up near Smolensk for two whole months. The German command began to have doubts that it would be able to take the capital of the USSR before the onset of cold weather. “The whole situation makes it increasingly plain that we have underestimated the Russian Colossus, who consistently prepared for war with that utterly ruthless determination so characteristic of totalitarian states,” Halder wrote in his diary.

Soviet troops defending Smolensk.

Global Look PressThe forces of Army Group South were steadily advancing toward Kiev, the capital of Soviet Ukraine, the loss of which was unthinkable to Stalin. On July 11, the HQ and Military Council of the Southwestern Front received a telegram from the Kremlin: “I warn you that, if you take even one step towards withdrawing troops to the left bank of the Dnieper and do not defend the fortified areas on the right bank of the Dnieper to the last, you will all suffer a cruel punishment, like cowards and deserters.” Georgy Zhukov, who raised the possibility of Soviet troops around Kiev ending up in a “pocket”, was removed from his post as chief of the General Staff on July 29.

The city stood fast until, at the end of August, by Hitler’s decision, Heinz Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Group was removed from the German line of advance towards Moscow and sent south. Having broken through the Soviet defenses, on September 15, near the town of Lokhvitsa, east of Kiev, it joined the 1st Panzer Group of Ewald von Kleist, thus completing the encirclement of four Soviet armies.

About half a million Red Army soldiers were taken prisoner by the Germans. Colonel-General Mikhail Kirponos, commander of the Southwestern Front, Major-General Vasily Tupikov, his chief of staff and a number of other high-ranking commanders were killed while trying to break out.

Occupied Kiev.

BundesarchivA rapid thrust through the Soviet Baltic Region by Army Group North troops allowed the Wehrmacht to reach the shores of the Gulf of Finland in early August and cut off the principal Baltic Fleet base at Tallinn from the main Red Army forces. On August 27, ships mounted an operation to run the blockade out of the besieged city in the direction of Leningrad.

The fleet spent three days making its way through a dense network of Finnish mine fields under continual attack by Finnish torpedo boats and German aviation. “We proceeded from Tallinn to Kronshtadt under cover of German dive bombers,” Soviet sailors joked wryly. In the so-called ‘Tallinn Crossing’ (the Russian name for the evacuation), as many as 60 ships and up to 15,000 lives were lost: sailors, civilians and men of the 10th Rifle Corps.

Soviet Baltic Fleet destroyer.

Alexey Mezhuev/SputnikWhile heavy fighting against the Nazis and their allies was taking place in the European part of the country, the Soviet leadership decided to secure its southern borders. The Anglo-Soviet Operation Countenance to invade Iran, which was by then firmly in the sphere of influence of the Third Reich, began on August 25.

The allies toppled the pro-German Reza Shah Pahlavi and took the north and south of the country under their control. One of the main routes through which military supplies would be channeled to the Soviet Union from the Western powers under the Lend-Lease program was to be established through Iran within a short space of time.

British and Soviet troops in Iran.

Public DomainOn September 8, German troops took the town of Shlisselburg on the shores of Lake Ladoga, thus completing the land encirclement of Leningrad. From the north, the Soviet Union’s second most important city was blockaded by the Finnish army. Around half a million Soviet troops, almost all the Baltic Fleet’s naval forces and a civilian population of up to three million people found themselves trapped.

The only thread that still linked besieged Leningrad with the “mainland” was the water route across Lake Ladoga - the so-called ‘Road of Life’. It was used to bring in food supplies and to evacuate the population. Neither this lifeline nor transport planes could keep the city of several million people fully supplied, however, and, during the winter, Leningraders encountered appalling hunger.

Besieged Leningrad.

Anatoly Garanin/SputnikThe crushing of the Southwestern Front at Uman and Kiev allowed the Germans to mount an offensive on coal-rich Donbass and strategically-important Crimea, which Hitler described as an unsinkable Soviet aircraft-carrier threatening Romanian oil.

On September 26, formations of General Erich von Manstein’s 11th Army broke through Soviet defenses on the Perekop Isthmus and fought their way into the interior of the peninsula. Fierce resistance by Soviet troops and considerable losses, however, prevented the Germans from taking Sevastopol at a stroke. The siege of the Black Sea Fleet’s principal base, which started on October 30, was to last a total of 250 days.

Two German army soldiers observe from a vantage point the city of Yalta.

Heinrich Hoffmann/Mondadori via Getty ImagesThe key battle of 1941 - the Battle of Moscow - erupted in early October. At the very start, the Red Army suffered an appalling disaster. Because of mistakes on the part of the Soviet command, which failed to anticipate the enemy’s principal directions of attack, the main forces of the Western and Reserve fronts were encircled and smashed near Vyazma. The Soviet troops had over 900,000 men killed, wounded, captured or missing. The beleaguered forces, nevertheless, continued to fight on until October 13, tying up 28 German divisions.

The Germans found the road to Moscow lying practically unobstructed. All available forces, including military academy cadets, had to be hastily sent to the defensive lines until reserves arrived. The capital was gripped by panic for several days, accompanied by a mass exodus of the population from the city, as well as looting and pillaging.

Captured T-34 near Vyazma.

BundesarchivFor the Wehrmacht, the road to the Soviet heartland was not a walkover, however. As a result of many months of dogged resistance and continual counter-attacks on the part of the Red Army, the German troops were worn out and overstretched. Trained personnel with valuable combat experience from the Polish and French campaigns were perishing in bloody battles. The comprehensive mining of the approaches to the city hampered the movement of armor, while the onset of cold weather was killing off horses on a large scale and leading to supply disruptions.

The Germans were counting on making a decisive push towards Moscow, unaware that substantial new Red Army reserves were at that moment concentrating in the capital. On December 5 and 6, the troops of several Soviet fronts took the enemy completely by surprise with the launch of a large-scale counter-offensive. The stunned Wehrmacht was pushed 100-250 km back from the capital, while in several sectors the withdrawal became a panic-stricken rout.

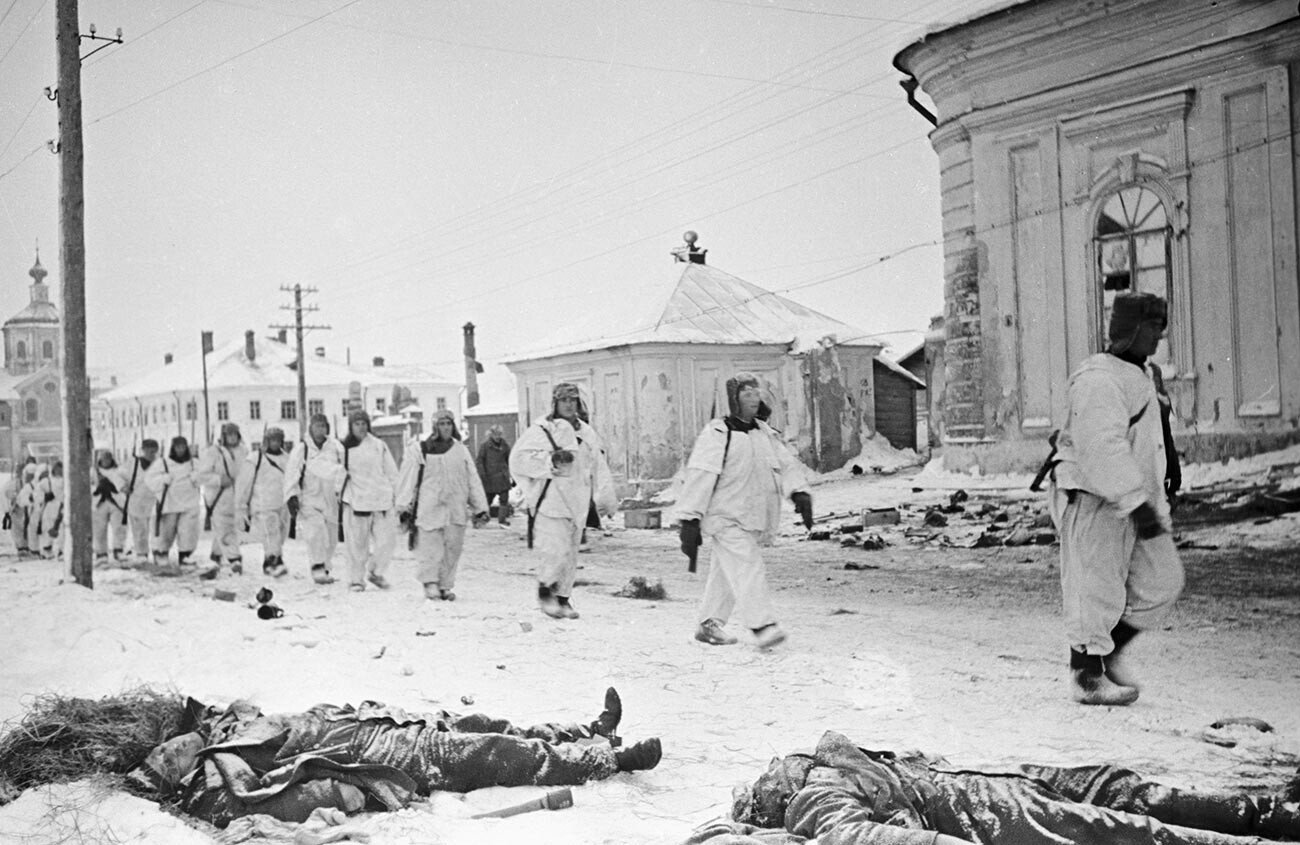

Soviet soldiers passing by dead Nazis along liberated streets of Kalinin.

Samaryi Guraryi/SputnikThe commander-in-chief of Germany’s ground forces, Walther von Brauchitsch, and the commander of Army Group Center, Fedor von Bock, were dismissed by Hitler. Heinz Guderian, who was also relieved of his command, later wrote in his Memories of a Soldier: “The advance on Moscow collapsed. All the sacrifices and efforts of our valiant troops proved to have been in vain.”

German prisoners of war outside Moscow in December 1941.

Anatoly Garanin/SputnikThe triumph outside Moscow was of colossal significance both for the USSR itself and for the member-countries of the anti-Hitler coalition. The Soviet leadership believed that the enemy was broken and that the time had come to undertake a large-scale offensive along the whole length of the Soviet-German front. Despite the failure of the “blitzkrieg” strategy, subsequent events were to show that it was still early to write the Germans off.

A woman embracing a Soviet soldier in a liberated village.

Ivan Shagin/SputnikIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox