The largest Soviet passenger airliner, an Il-86, in the air, 1984

Sozinov/SputnikIt was a Sunday evening and Yevgeny Volodin was boarding a plane at Vnukovo airport outside of Moscow. The 26-year-old native of Novokuznetsk, a carpenter at a local furniture factory, had a travel bag on him with six bottles of saltpeter in three packs of two tied with adhesive tape. Nobody checked their contents. The date was March 17, 1991, the day when the referendum on the preservation of the USSR was held.

The regular Moscow - Novosibirsk flight was packed. The aircraft was carrying 365 passengers, 20 of whom had babies in their arms. The first two hours of the flight went without any incidents. That was until Volodin got up from his seat. He had been waiting for a long time for the aisles to get free, but they remained busy: first, the cabin crew served food, then drinks, then they collected the garbage. His patience ran out, so he got up to go to the toilet closest to the cockpit. And he took his bag with him.

“Two hours after take-off, everybody who was in the cockpit felt a powerful knock on the door,” recalls Yury Sytnik, the co-pilot on that flight.

What they took for a knock was in fact an explosion. Volodin had spent a minute in the toilet, then opened the door and threw two incendiary bombs into the aisle. He did not manage to throw the third one as the area around the door to the toilet was already ablaze. Volodin was blocked inside the toilet.

IL-86 passenger plane on the airfield

Dmitry Sokolov and Vladimir Yatsina/TASSUnaware of what had happened, the instructor pilot, Anatoly Ekzarkho, told the flight engineer: “Check out who is trying to get in here.” The flight engineer opened the door and a cloud of flame blew into the cabin. “Nobody escaped it: hair and eyebrows were singed, all exposed skin was burnt. It was a good thing that the flight engineer slammed the door almost immediately,” says Sytnyk.

Inside the cabin there was chaos. In a panic, some passengers ran to the exits and tried to open the hatches. Others ran away from the fire, to the tail of the aircraft, which could upset its balance. But, they did not remain standing for long.

“[Ekzarkho] reacted instantly: as is prescribed during a fire, he put the airliner into a steep dive. The Il-86 was rushing to the ground at a speed of 70-80 meters per second, so there was zero gravity, like in space,” says Sytnik.

The cockpit was already filled with acrid smoke and Ekzarkho was losing consciousness. Thankfully, Yury Sytnik had managed to put on his oxygen mask in time. Now he was looking for the nearest airport.

“I sent out a message: ‘To everyone hearing us! This is board 86082. We are located 160 km from the city of Serov. We are falling, we are on fire.’ Because of the smoke, I could hardly see the readings on the dashboard. We were above the Ural Mountains and it was dangerous to go below 2,700 meters,” he says.

Soon, another problem emerged.

The fire was extinguished 20 minutes later. It was put out by the aircraft commander, Yakov Shrage, the flight attendants and two passengers: an investigator with a prosecutor’s office and a major, who in the past had burned twice in a tank in Afghanistan. The hands of both were burned to the bone. They used up 14 fire extinguishers and prevented the wiring from burning altogether, which would have shut down the on-board equipment.

By that time, Anatoly Ekzarkho had come to, but then the navigator lost consciousness. Fortunately, he had already managed to put the plane on a course towards the Koltsovo airport in Sverdlovsk [present-day Yekaterinburg]. The smoke began to dissipate and the crew could see the dashboard again. However, now they had another problem - they could not see the runway.

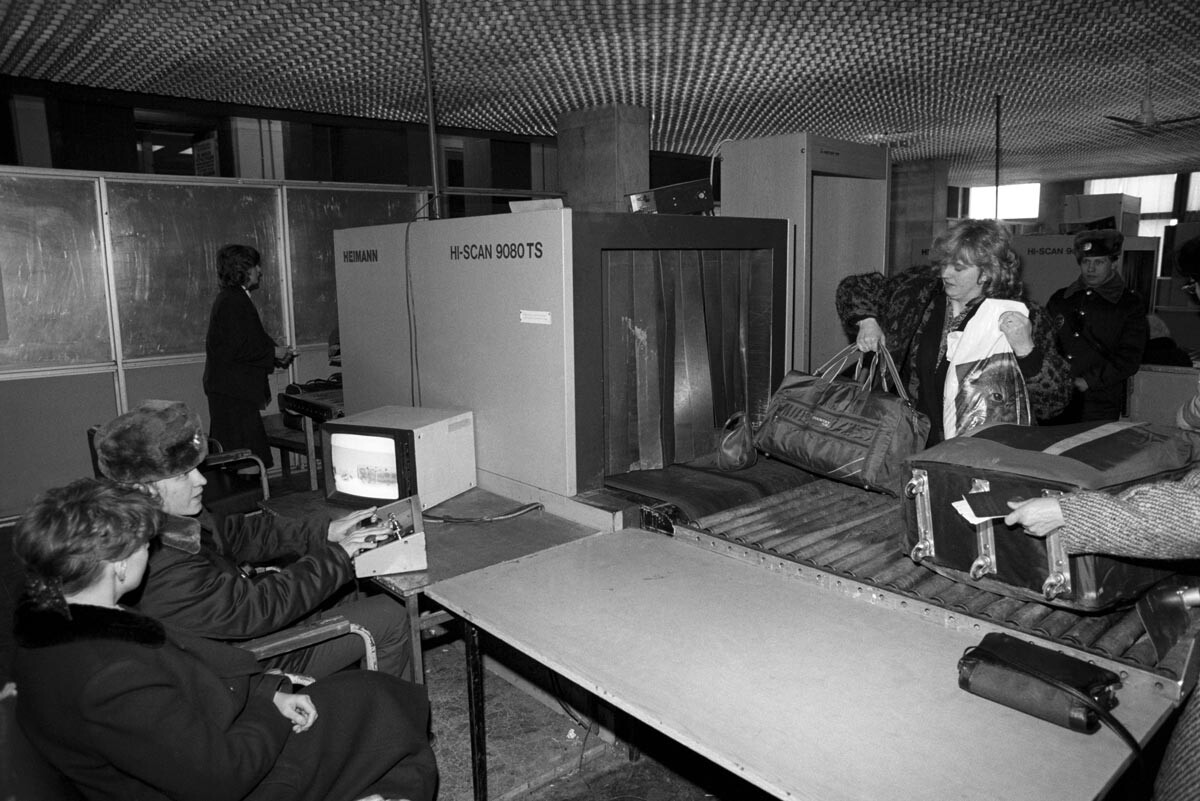

Checking passengers' luggage at Vnukovo Airport, 1991

Nikolay Malyshev/TASS“The distance is 8 km, the height is 400 m,” the airport traffic controller reported. “Can you see the runway?”

“We can't,” was the response.

“Then, my hand accidentally, or on a hunch, touched the cockpit window. It was covered in soot and not just ordinary soot, but soot filled with some kind of needles half a finger long. It settled on all the panes and did not let the light in from the outside,” says Sytnyk. A second later, clearings the size of a saucer were made on the glass for the pilots to see through, and they saw the lights of the runway 6 km away. That happened literally a minute before the plane's scheduled descent would have turned into an uncontrolled fall.

The plane landed and taxied as far from the airport terminal as possible. The door in the front section of the fuselage was opened and a team of commandos rushed up the airstair to enter the plane.

“The terrorist was smoked out of the toilet with a smoke bomb and then all hell broke loose! A commando officer fired into the air, then stuck the barrel of his pistol into the man’s mouth (he must have knocked out his teeth) and yelled: ‘Bastard, my sister is on this plane, I’ll tear you to pieces!’ And then he suddenly switched to a completely calm voice: ‘Tell me who sent you’,” recalls Sytnyk. There was another officer next to them, with a voice recorder on the ready.

Later, Sytnik would be told that Volodin had no plans to hijack the plane and had no intention of putting forward any demands. It was a terrorist attack with the sole purpose of leaving no-one alive. “When his trial was being prepared, the KGB explained to us that he had fallen under the influence of Armenian nationalists, who wanted to draw attention to the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh. Apparently, Volodin was an extremely suggestible person. In any case, instead of capital punishment, he – as far as I heard – was sent to a psychiatric hospital,” says Sytnyk.

During interrogations, it turned out that the suicide bomber had spent 18 months studying the airport’s screening system and boarding procedure. He chose the largest passenger airliner, an Il-86 (this model was decommissioned in 2010) and designed an explosive device without metal parts, so that it would not be detected by sensors during boarding. At the time, Soviet airports did not have a screening system similar to what we have today: there were only metal detector frames for checking for firearms. Nobody was interested in or worried about some bottles in someone’s luggage.

Crew of an Ilyushin-86 passenger aircraft. Vnukovo Airport, 1981.

В. Akimov/SputnikHis plan was to detonate three bombs in three different parts of the plane. In that scenario, the airliner would have had no chance to land. Together with the crew, there were 382 people onboard. But the hustle and bustle in the aisles and Volodin’s impatience interfered with his plans and he decided to blow all the three bombs up in one place. Thus, it was chance and the crew’s prompt actions that helped to avoid a fatal situation. Not a single person was fatally injured that night.

Later, Yury Sytnik was told by the KGB that, thanks to the information received from Volodin, a number of similar terrorist attacks in St. Petersburg, Kaliningrad and other cities had been prevented.

“A great many things happened in life after that incident. I was awarded an order ‘For Personal Courage’ [this order was awarded to the entire crew]. I had to land a plane on an unlit airfield in Baghdad at night, scaring the politicians and journalists onboard. When returning from Syria, my plane was almost shot down by an American fighter over Turkey. But I’ve never had to experience again what I experienced on the night of March 18, 1991. I think it’s for the best,” says Sytnyk.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox