“Moscow should adopt a European look. Historical monuments and buildings, of course, will remain, but the current Asian character of the city – all these crooked streets, weirdly constructed buildings and the strange coloring of houses – must be destroyed.” Surprisingly, these words were spoken long before Joseph Stalin, in 1913, when Nikolay Schenkov, a deputy for the Moscow Duma, was sharing his vision of the future Moscow with the newspaper ‘Voice of Moscow’. Schenkov was the head of Moscow Duma’s ‘Commission for the Improvement of the City’ that was established with the aim of adjusting the city’s planning for the needs of the epoch.

However, the Commission didn’t have the chance to implement its projects, due to the 1917 Revolution, but it’s remarkable that even before the Stalinist industrialization and urbanization started, the need for replanning Moscow was apparently obvious. Roman Klein, one of the city’s prolific architects of the era, said in an interview with ‘Voice of Moscow’: “[Moscow] is a large trading hub, whose population is increasing every year, the need for housing is growing and land is becoming more expensive. Whether we want it or not, houses will increase in height, overshadowing small mansions and rising above the churches’ domes.”

Tverskaya street in Moscow before the Revolution

Public domainThe events following the 1917 revolution proved Klein absolutely right. From just 1918 to 1924, over 500 thousand people were relocated from Moscow suburbs and poor districts into downtown Moscow, occupying the manors of the former nobility and the city buildings – former posh hotels and high-class apartments, turning them into communal living quarters. Still, the need for housing was desperate, with many more people flocking to Moscow to work and study amidst the economic crisis of the 1920s. They all needed a place to live, so, during the 1920s, several teams of architects suggested their plans for the reconstruction of Moscow. None of them, however, were considered sufficient for implementation.

In 1932, a closed contest for the general plan of Moscow was run, with great architects, such as Le Corbusier, Hannes Meyer (second director of Bauhaus) and Ernst May (creator of the ‘New Frankfurt’) submitting their projects. Le Corbusier’s plan was the most radical one. “It’s all piled up in a mess and without a specific purpose,” Le Corbusier stated. “In Moscow, everything needs to be destroyed and rebuilt back again,” said the architect whose plan was to demolish the whole city center and recreate it using a rectangular grid of streets. Ernst May estimated that “Moscow as it is now is able to rationally house no more than 1 million residents.”

Meanwhile, by the beginning of the 1930s, the city held over 3 million people. With a really complicated network of streets, lanes and boulevards, streets still paved in many places with cobblestone, wood and, without pavement, Moscow wasn’t fully ready for industrialization with its heavy traffic.

In 1933, a design bureau called the Design workshops of the Soviet of Moscow was specially established to create the project for Moscow’s replanning. The so-called ‘General Plan for Moscow’s reconstruction’ was finished in 1935, but, by then, lots of construction had already begun: the first subway line, Sokolnicheskaya, was finished and preparations for creating the Moskva-Volga Canal had started. In the center of the city, the buildings of V. I. Lenin State Library of the USSR, Hotel ‘Moskva’ and the current State Duma were founded and rapid replanning of the streets began. Obviously, it involved demolishing some important parts of the old town.

The demolition of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, 1931

Public domainThe epoch of Moscow’s reconstruction coincided with an active anti-religious campaign led by the authorities. In 1928, the mass destruction of Orthodox churches had begun. The Bolsheviks did not hesitate to demolish old churches if they interfered with the expansion of roads – and, of course, many were demolished out of pure propaganda reasons and anti-religious zeal. Many churches were closed, with domes taken down, and used for anything from a grain storage to a factory or a research institute. Likewise, the whole districts of old low-rise buildings, often including historical manor houses, were under threat. According to the plan, all significant squares of the city, including the Red Square, were to increase at least twice, due to the demolition of the buildings around them. The width of almost all important streets of the city, avenues and highways also had to increase to 30-40 meters or more, due to the demolition and transfer of buildings that stood there.

Here is a list of the most important architectural losses.

– Simonov Monastery. Constructed in the 14-17 centuries and demolished in 1920-1930, the Simonov monastery was a historical monument and a memorial place. After the demolition of most of the buildings and the destruction of the monastery’s cemetery, a new Palace of Culture for ‘ZIL’ (a nearby automobile plant) was constructed in the monastery’s place.

Simonov Monastery

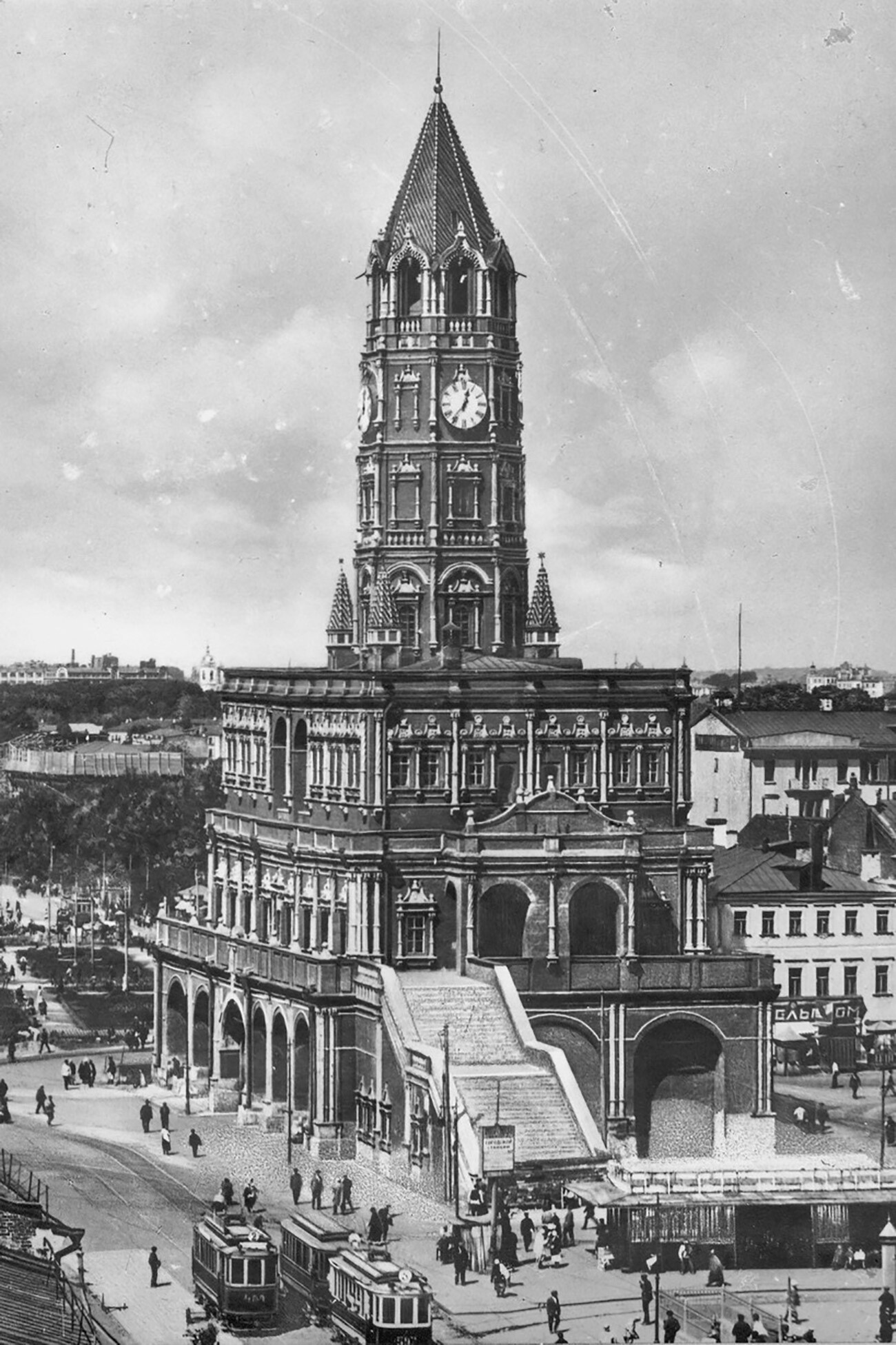

Public domain– Sukhareva Tower. Built in the Moscow Baroque style in 1692-1695, the tower housed the Moscow School of Mathematics and Navigation and, later in the 18th-19th century, many stores and workrooms were located there. Unfortunately, the tower was situated right in the middle of the Sadovoye Ring, a circle-shaped Moscow street that needed widening. Sukhareva Tower was, in the end, demolished in 1934.

Sukhareva Tower on Sukharevskaya square in 1927

Public domain– The old Kitay-Gorod wall. The fortress wall surrounding Moscow’s downtown was constructed in the 16th century by Italian architects. By the 1930s, it had long lost its fortification purposes and was just an impressive historical monument in the center of the city. But, the wall with its many towers was demolished in 1934-1935. Only one piece of the wall, about 150 meters, remained intact behind the ‘Metropol’ hotel.

The Kitay-gorod wall, 1934, before demolition

Public domain– Cathedral of Christ the Savior. The cathedral took 40 years to build, it was finished in 1883 and dedicated to Russia’s victory over Napoleon in 1812. The 103-meter cathedral was blown up in 1931. The demolition was supposed to make way for the colossal Palace of the Soviets to house the country’s legislature, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Construction started in 1937, but was halted in 1941, when World War II started. In 1958, the swimming pool ‘Moskva’ was dug in its place. In 2000, the cathedral was rebuilt according to its original design.

Strastnaya square in Moscow (now, Pushkinskaya) before the Revolution. Strastnoy Convent in the center

Public domain– Strastnoy Convent. Founded in 1654, the convent dominated Pushkinskaya Square, one of Moscow’s central squares. It was demolished in 1931 and, later, ‘Pushkinsky’ cinema theater took its place.

The construction of Novy Arbat (Kalininsky Prospekt) in Moscow. The houses to the left are being constructed among the remains of a historical district.

NIna Kanevskaya/Sputnik– The urban area in the place of the current New Arbat Avenue was doomed for demolition along Stalin’s General plan of 1935; however, the actual demolition didn’t start until after the war, in the late 1950s – early 1960s. During the avenue’s creation, a whole historical district was demolished.

In general, the number of historical buildings officially protected by the state fell from 216 in 1928 to 74 in 1935. Of course, there were more than 74 historical buildings remaining in Moscow after 1935, they just weren’t all officially recognized. But, the numbers do show the scale of demolition. For example, all facades on Tverskaya Street were recreated, almost all churches in the center demolished and many buildings renovated beyond recognition. Some of the remaining historical buildings were moved without deconstructing them. But, the realization of the General Plan was halted in 1941 with the start of World War II.

Gorky Street (now, Tverskaya street) after reconstruction.

Semen FriedlandApart from the architectural monuments that were irreversibly lost, the city, at the same time, gained a great deal. Thanks to the widening of the central streets and creating radial avenues and highways, Moscow became ready to accommodate more people and, most importantly, to make transportation inside a vast city possible.

After the war, continuing the implementation of the General Plan, the new districts of Moscow surrounding the old city center were created following a grid principle, which made public transportation easier. The Moscow Automobile Ring Road was planned in the late 1930s and completed in 1962, a road that has crucial importance in the city’s transport. The Moskva-Volga canal was constructed (using the labor of convicts from the GULAG system), which allowed a shorter connection between the rivers and boosted the development of river transportation in Moscow Region.

Bolshaya Kolkhoznaya (Bolshaya Sukharevskaya) Square in Moscow, 1957.

Mikhail Ozersky/SputnikThe embankments of the Moskva River, 52 kilometers in total, were faced with granite, three bridges were reconstructed and nine new bridges were built. Many new water reservoirs around Moscow were created by building dams and new technologies were implemented in water cleaning and filtering. New public parks, most notably the Gorky Park, were also created, eventually making Moscow the greenest city in the world. The realization of the General Plan, although with some serious omissions, continued throughout the later years of the USSR’s existence.

Vital needs of a gigantic growing city were met in a space of about 20-30 years and it was more difficult, considering the fact that the realization of the General Plan was hindered and undermined by World War II. Although a number of cultural monuments were lost, the Stalinist reconstruction generally made Moscow what it is today and allowed for further development of the city that has continued after the fall of the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox