The first day of the week in the U.S., Canada, Brazil, Japan, Israel and a few other countries is Sunday, not Monday. It used to be the same in Russia and the Russian Empire – and this idea is based on the Bible.

The book of Genesis of the Old Testament contains a description of the creation of the world, which lists the successive days of creation, from the first to the sixth. It is these names (day one, day two, etc.) that the days of the week are still in Hebrew. “Then God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it he rested from all his work which God had created and made” (Gen 2:3).

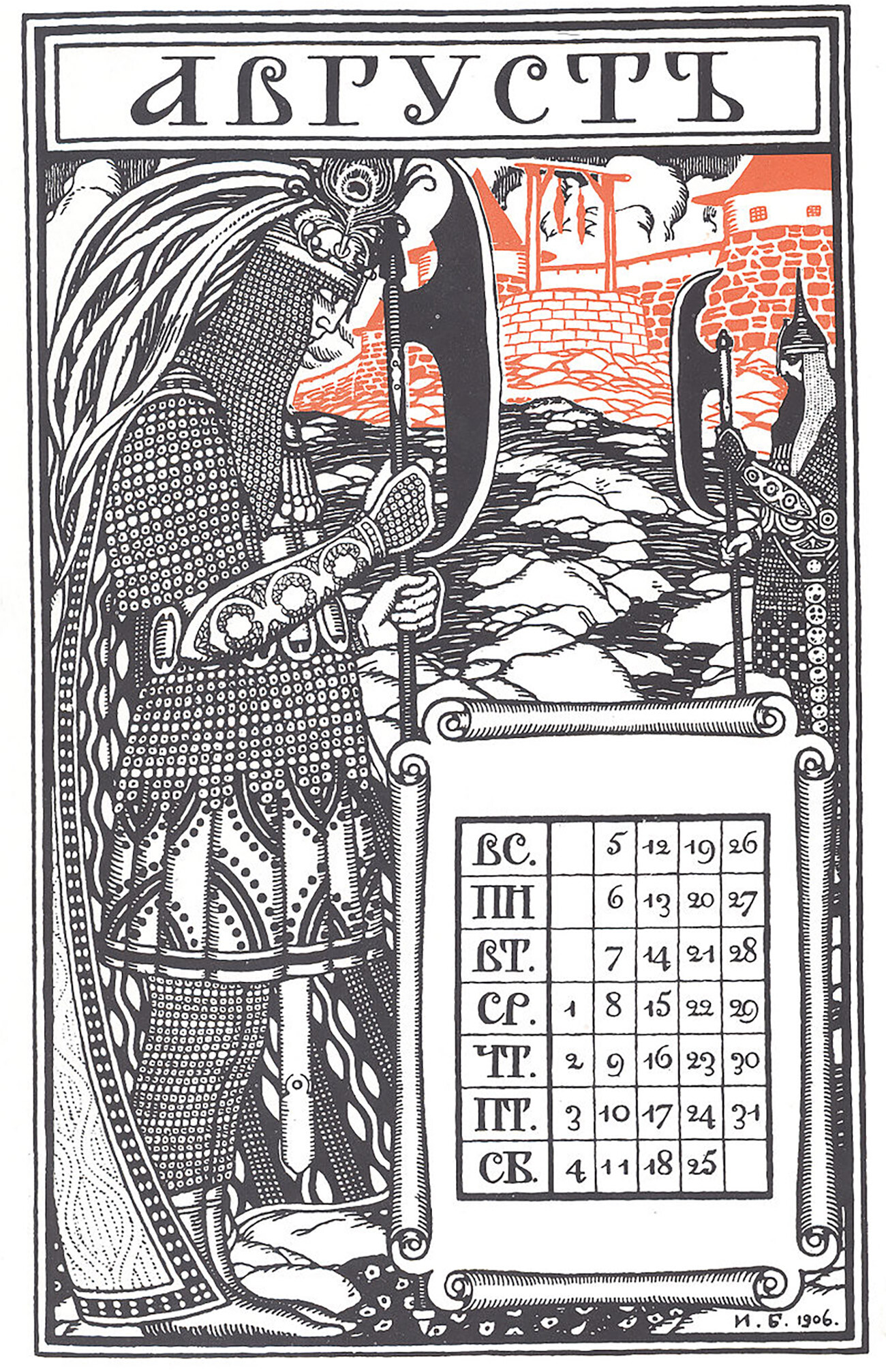

A Russian calendar for August 1906, designed by Ivan Bilibin. Note that all weeks start on "Воскресенье" (Sunday)

Public domainSaturday in Hebrew, rather than being called “day seven”, is called Shabbat (derived from the word “to rest”) and finishes the week. Thus, in Judaic, as well as in Christian traditions, the week traditionally began with Sunday and it was so in Russia until the Revolution of 1917. The names of weekdays in Russian are proof of that. Wednesday in Russian is called ‘sreda’, which means “middle” in Russian. Obviously, Wednesday is in the middle only if the week starts on Sunday.

Also, in Slavic languages, Monday is called ‘ponedelnik’, which means “the one coming after nedelya”, where ‘nedelya’ is how the first day of the week was called and the whole week was called, also. ‘Nedelya’ can be translated from Russian as “no-doing”, as Sunday was the day for the Sunday service and Russian peasants didn’t normally work on Sundays.

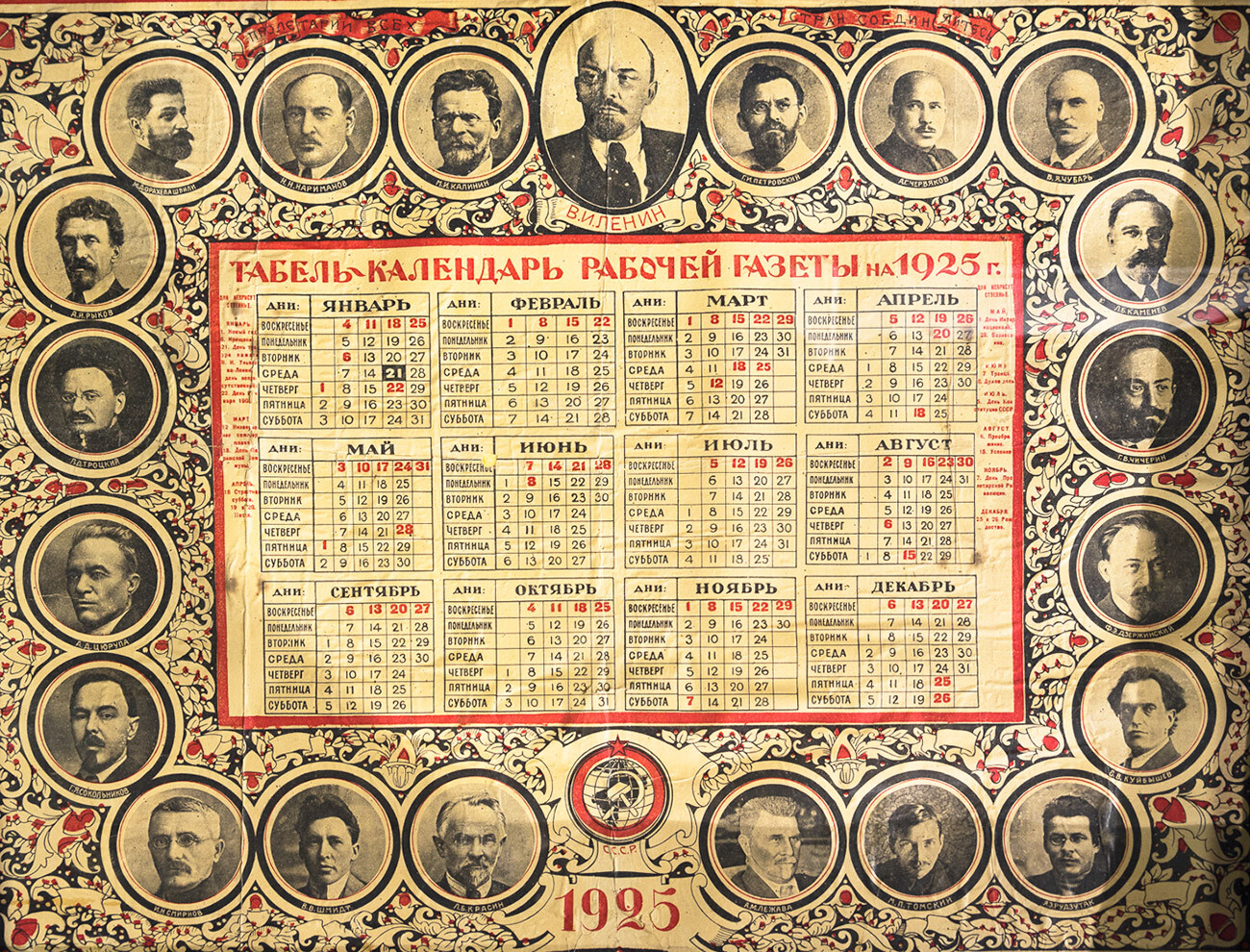

A Soviet calendar for 1925, all weeks still begin on Sunday

Public domainThe Bolsheviks fought the Orthodox religion and the church and one of their first decrees, signed in February 1918, replaced the Julian calendar (so-called ‘Old Style’) with Gregorian one (‘New Style’), which distinguished church calendar (the Russian Orthodox church used and still uses Julian calendar) from the secular, “official” one and also made Russia keep time with “almost all cultured peoples”, as the decree stated. However, Sunday was still the first day of the week in the early years of the USSR.

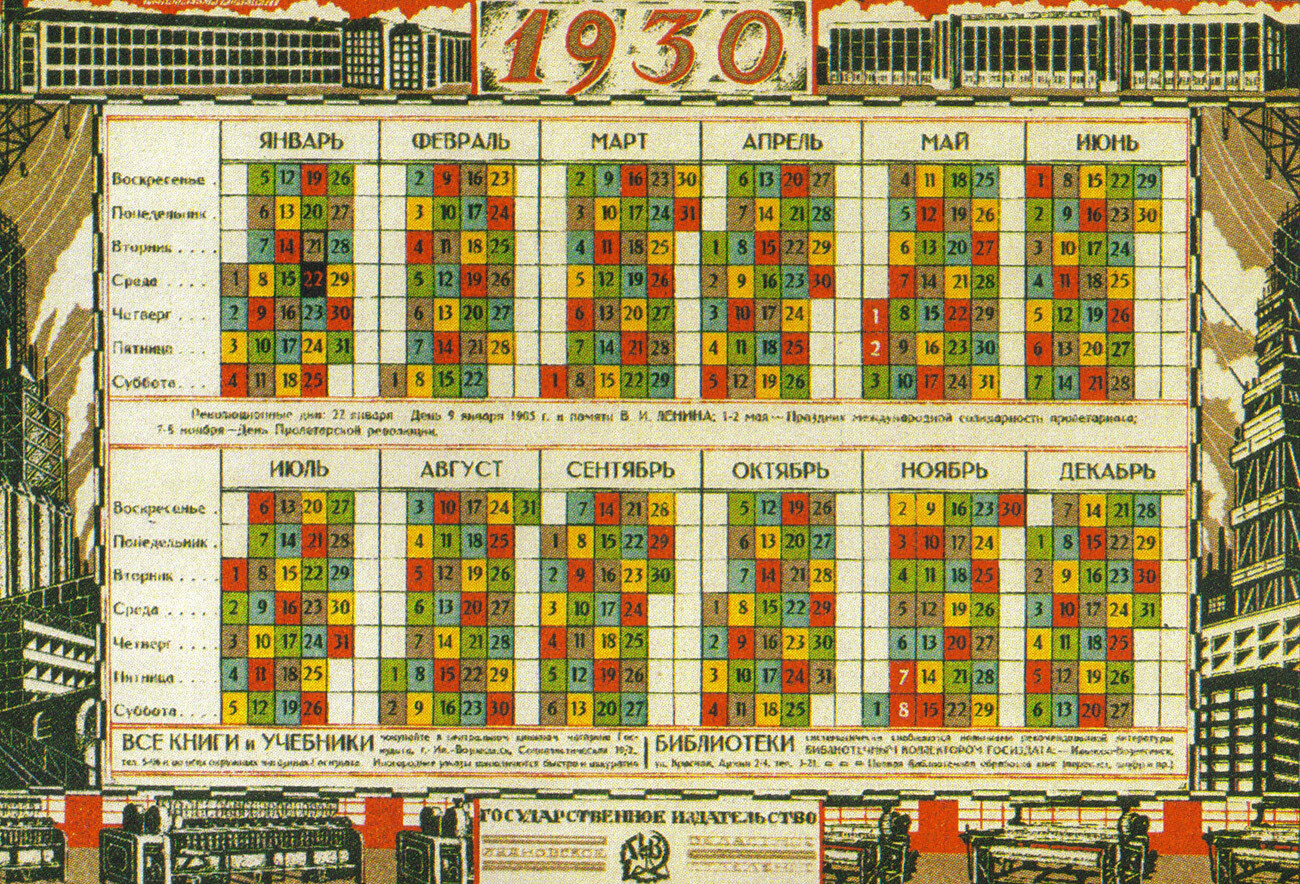

A 1930 Soviet calendar with 5-day 'continuous production weeks'

Public domainOn October 1, 1929, weeks were reformed in Russia – new 5-day weeks were introduced. They were called ‘continuous production week’ – people worked for four days and, on the fifth, they rested. And so it continued for a whole year’s cycle, which consisted of 72 five-day weeks, now. In order not to overlap the days off for employees, the workers were divided into five groups marked in the calendar in yellow, pink, green, red and purple. With this system, the mills, plants and other enterprises could operate without stopping all year round, as there were no common days off for all workers at once.

The five-day calendar also was an ideological tool. It distorted the Christian calendar of holidays, which was very useful for Bolshevik anti-religious propaganda. However, the new calendar wasn’t popular with the people at all. It often happened that husband and wife were in different color groups, and so didn’t have common days-off, which complicated their lives even more. In 1931, a six-day week with fixed days-off for everyone was introduced.

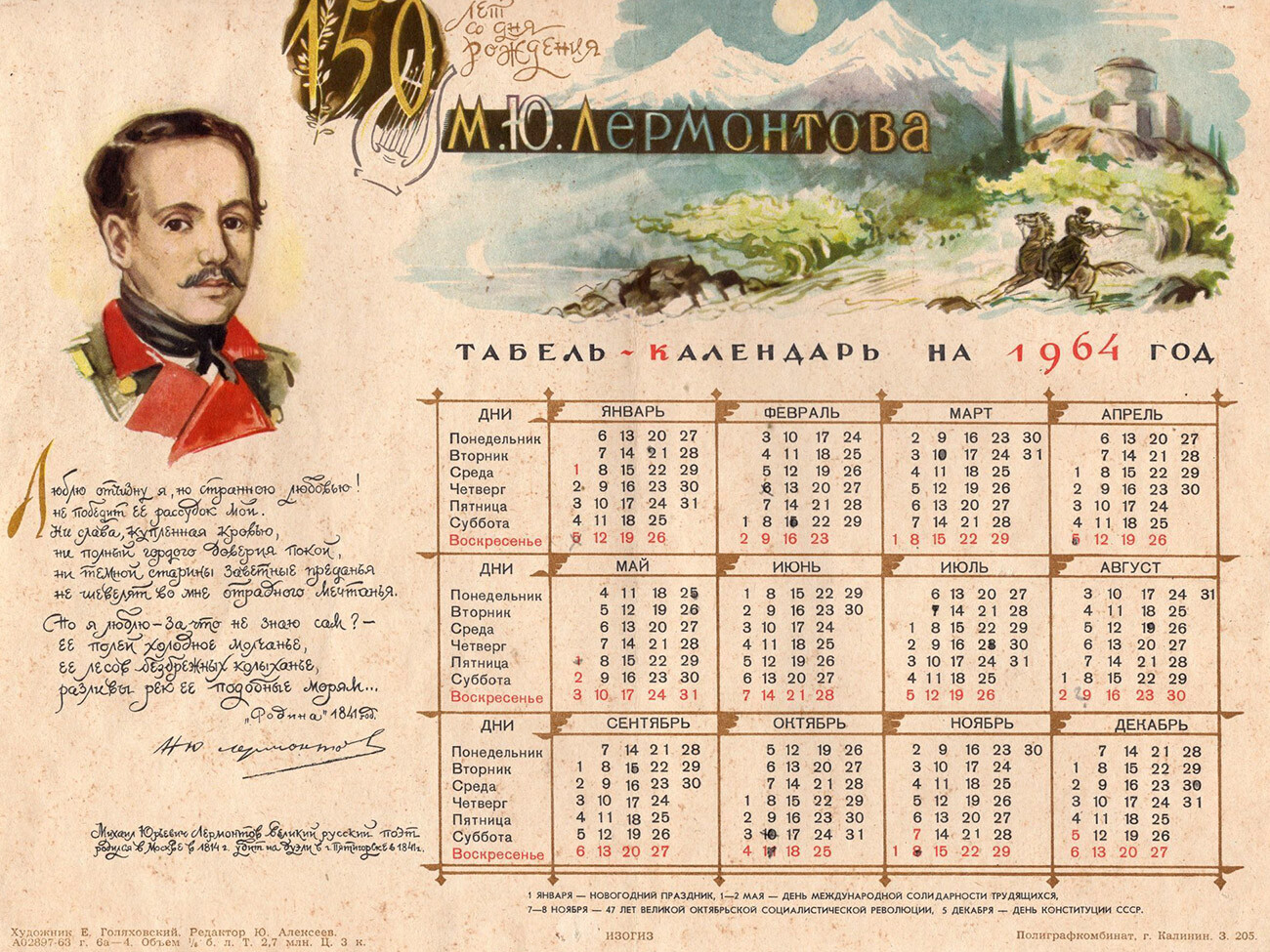

A 1964 Soviet calendar (dedicated to the 150th anniversary of poet Mikhail Lermontov), with 7-day weeks beginning on Monday

Public domainIt was only in 1940 when the USSR returned to a seven-day week. “Transfer work in all state, cooperative and public enterprises and institutions from a six-day week to a seven-day week, counting the seventh day of the week – Sunday – as a day of rest,” the decree said, so, starting from 1940, Monday officially became the first day of the week in the USSR.

With time, some Socialist-oriented states made Monday the first day also – for example, the DDR in 1970. In 1978, the UN recommended that Monday be made the first day of the week in most countries. It was established in 1988, according to ISO 8601, an international standard for exchange and communication of date and time-related data.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox