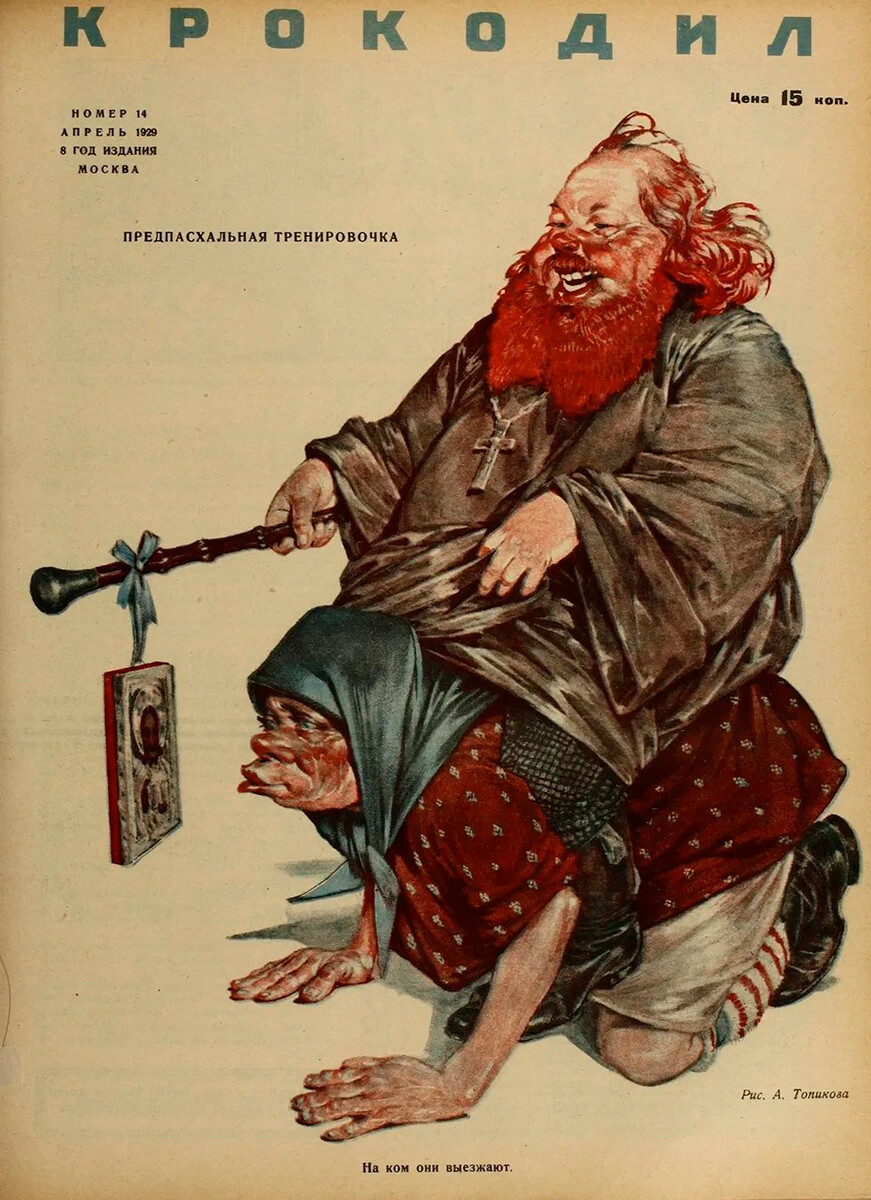

'Krokodil' magazine cover

Public domainAtheistic and anti-religious propaganda was a crucial element in the Bolshevik effort to create the new Soviet man. Revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin took Marx’s quote, “Religion is the opium of the people”, and made it a national slogan that reflected state policy. Lenin and his supporters believed that if deprived of God then people would come to the conclusion that their lives, as well as the fate of the country, depended solely on their own efforts and not a heavenly power. Lenin’s message was welcomed by many because starting at the end of the 19th century the Russian Orthodox Church often proved itself an institution that inhibited society’s modernization. In large part, the clergy was composed of people who held very conservative political and social beliefs. Such attitudes were a factor that contributed to the collapse of the Russian state in 1917, and which led to civil war and the subsequent millions of lives lost.

Red Army soldiers carry church utensils out of the Simonov Monastery in Moscow, 1923

SputnikThe Bolsheviks created many propaganda posters that depicted the clergy cartoonishly fat and repulsive, wearing robes and with long beards, and who were accused of keeping the people ignorant. Many churches and places of worship were closed and converted into buildings for economic purposes. On top of it, valuable sacred items were confiscated from churches for the “needs of the starving”. For example, these included ritual items made from precious metals; as well as church bells that were melted to make weapons and ammunition for the Red Army.

Read more here about how the Bolsheviks persecuted the Church.

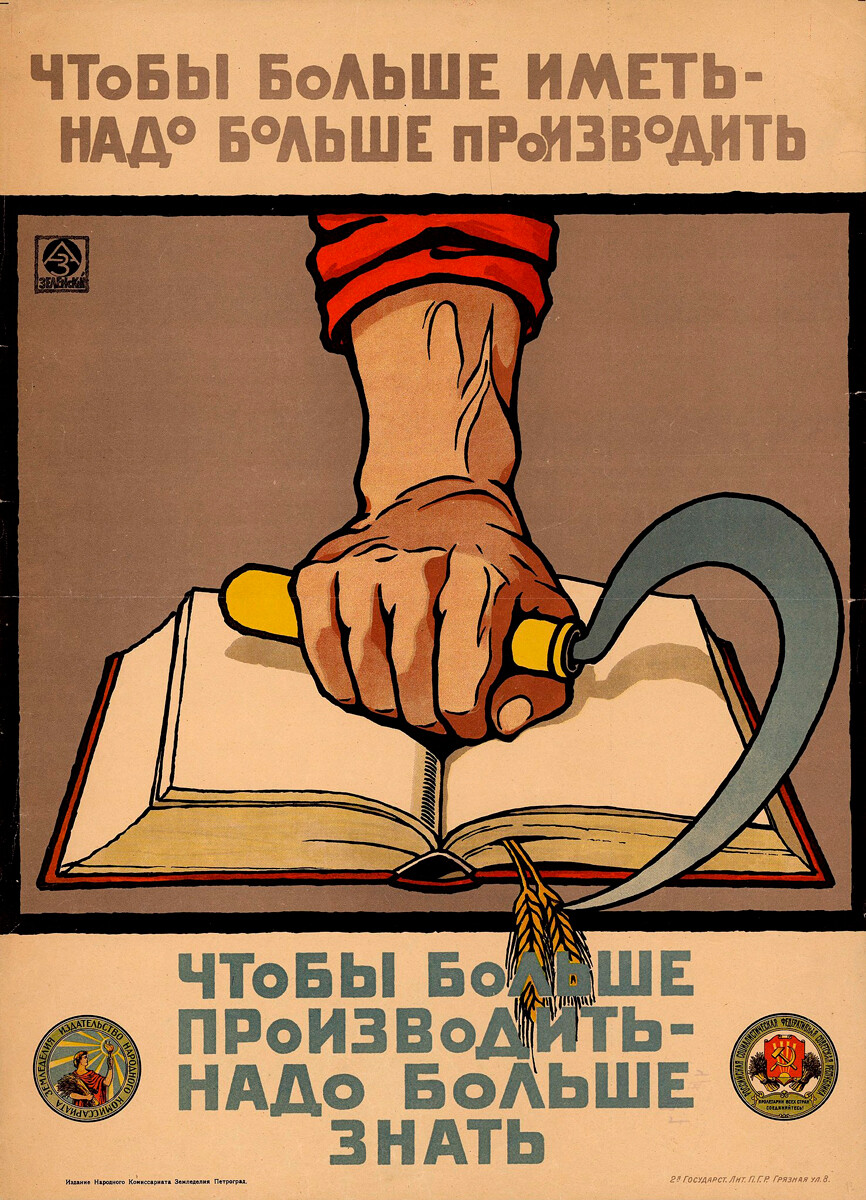

"In order to have more, it is necessary to produce more. In order to produce more, it is necessary to know more."

Public domainSeveral years prior to the 1917 Revolution, according to different estimates, only 20% of the Russian population knew how to read and write. The new ruling class – the workers and the peasants – had to be literate and educated in order to fully participate in social life and to increase their productivity. Hence, one of the earliest and most widespread campaigns undertaken by the Bolsheviks was the fight against illiteracy and the promotion of education.

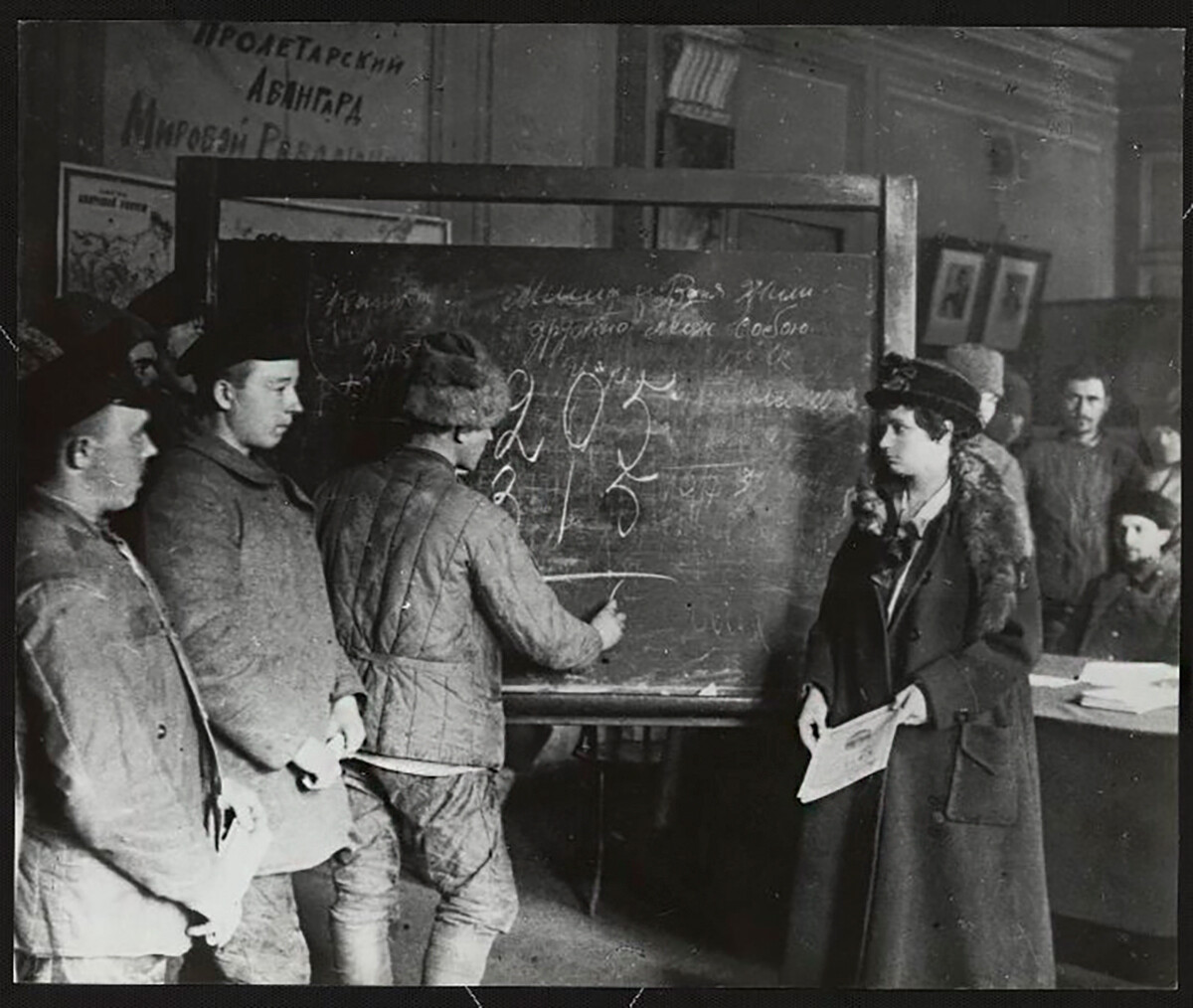

Classes to eliminate illiteracy in Petrograd, 1920

Arkday Shishkin/MAMM/MDFIn 1919, a decree was issued obliging the entire population, aged 8 to 50 years old, to learn how to read and write in Russian or their native tongue. Also, to facilitate learning, the Bolsheviks carried out a language reform. Within 10 years, about 10 million people were taught how to read and write and, as the 1926 census showed, about 50% of the people in villages were literate; by 1939, almost 90% of the entire population was literate.

In a collective, it's all for one, and one for all

Public domainThe Soviet government sought to build a society based on principles of an all-encompassing equality, where there’d be no poverty and misery, and income would be redistributed. The regime refused the principle of personal enrichment and the primacy of private property, which had been the engines of capitalism. Moreover, the use of items for one’s personal enrichment or enjoyment was shunned as a matter of ideology. One had to share everything they had with their fellow citizens. Ideally, one should give up what they didn’t need for themselves.

A senior worker shows employees how a lathe works, 1952

Ilya Arons/SputnikAnother prominent motto by Marx was: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” There should be neither rich nor poor, everyone should have almost the same income, everyone should work for each other’s benefit, and the fruits of their labor should be shared among the entire community; (something similar still exists in Scandinavian countries, which deeply incorporated the best Soviet principles in their social and political structures).

According to Soviet morality, people should strive and work not for their own enrichment and the subsequent acquisition of material goods but for the sake of work itself, and for the common good. They should take pleasure not in the consumption of material goods (this was the foundation of the capitalist consumer society) but rather, in the process of work itself and self-realization. In essence, it was a reasonable goal, in accordance with Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs.

It was expected that every person should work, as opposed to living off rent, interest, or at the expense of others. “Parasites” were harshly punished. Lenin put them in the same category as the rich and swindlers – both were enemies of the proletariat. “He who doesn't work, doesn't eat,” this was another popular Soviet motto. The Soviet Constitution stipulated the right to work, and every citizen received guaranteed employment. Most commonly, this happened by specific state order after graduating from a vocational college or university.

The 1960s saw the decree “on the increase of the struggle against people avoiding socially useful work and leading an anti-social parasitic lifestyle.” Sometimes, there were raids to hunt for such people – for example, officers could ask for your personal ID documents in public transportation during work hours and inquire why you weren’t at work.

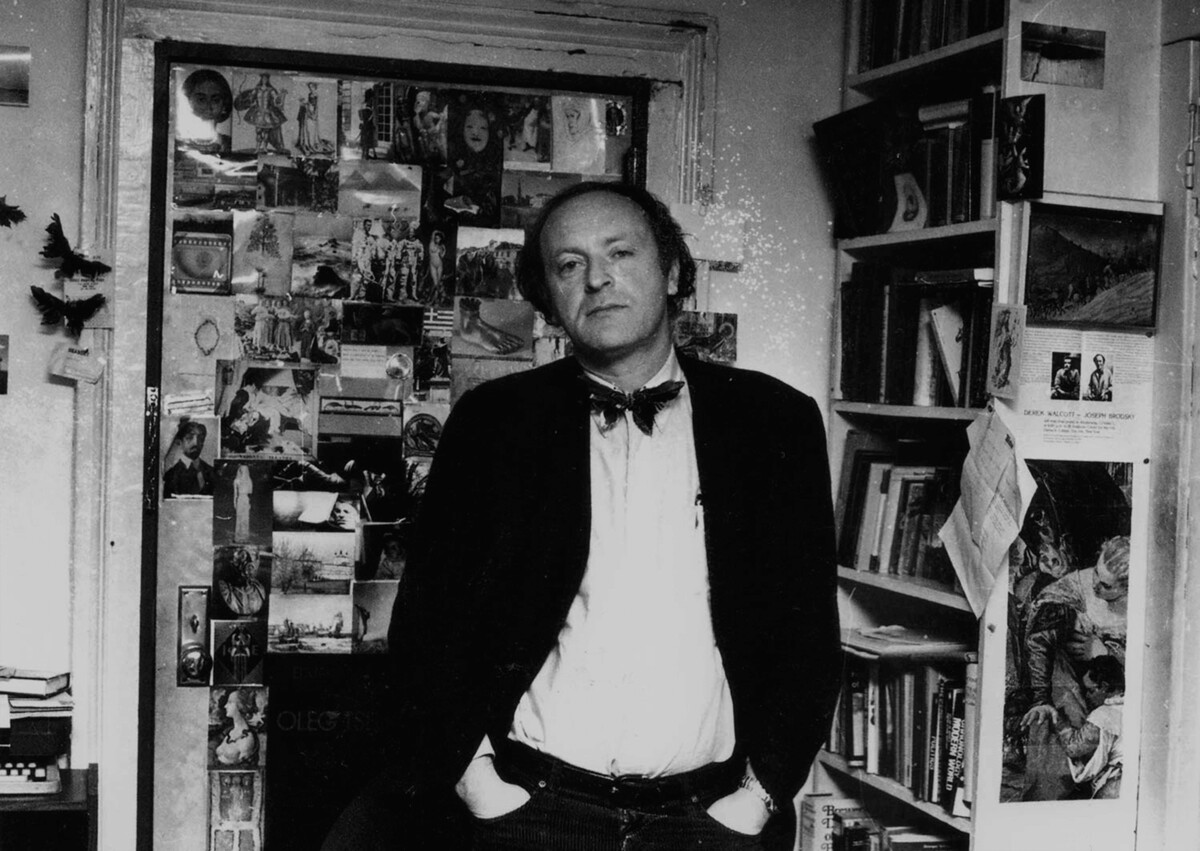

In 1964, Joseph Brodsky was charged with social parasitism and sentenced to five years hard labor (but spent only 18 months in exile, as his sentence was commuted after protests of his prominent friends)

Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty ImagesOften, the decree concerned dissidents; for example, poets, authors, and artists who were not part of the official Soviet cultural system and who had been turned down from official jobs. One of the most prominent examples of a cultural figure who suffered from this decree was poet Joseph Brodsky, who in the end was exiled.

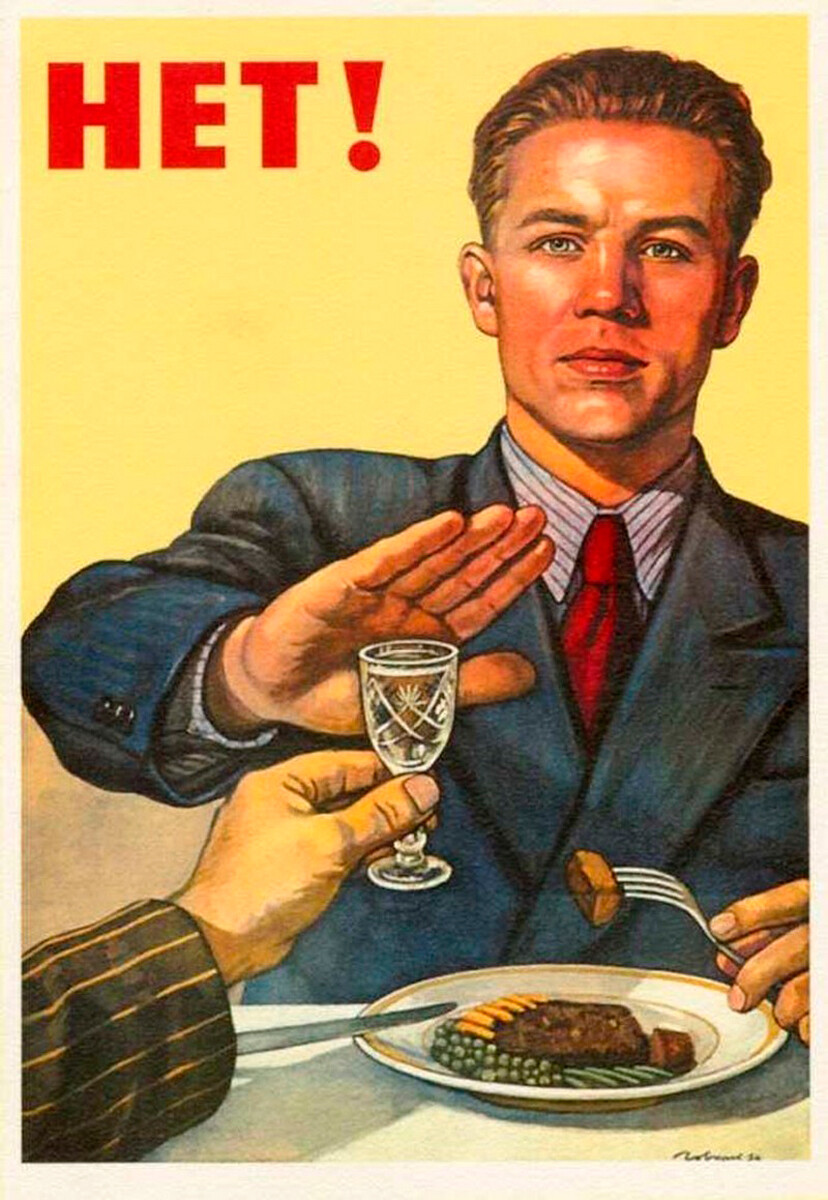

No!

Public domainThe Bolsheviks borrowed a lot from the Bible’s Ten Commandments in order to form their moral codex for the new Soviet man. For example, the principle of equality of all people (“there is neither Jew nor Greek”); the need to live for the common good and not your own benefit (one of the vows taken by monks); and treating a woman as equal to men without regard for her gender.

In the absence of religion that tried to correct human flaws, the Soviet government had to come up with new methods of propagating morality. One such way was a public reprimand. A person who did something immoral, who conducted themselves not according to Soviet standards, could be called before a collective assembly – be it at school, at a university or college, or at work – where they would be reprimanded and educated on morality. After all, such people “embarrassed” not only themselves but also the entire collective – and the Soviet Union. The authorities were especially harsh on drinking and dissolute lifestyles. They could even intervene in family matters and, for instance, denounce an unfaithful husband.

The Soviet government, for the first time in the history of Russia, exerted itself on the issue of the universal upbringing and education of children. This was no longer a family matter; rather, it was now a state priority.

Census of homeless kids in the USSR, 1926

TASSThe Soviet government was also active in fighting juvenile delinquency. After World War I, and especially after the Civil War, many children had lost their parents. Officially there were about 7 million street children (about 30,000 kids were living in orphanages). Many of those kids literally grew up “on the streets” and were, of course, thieves and beggars. The government took the street children crisis under its control. A special Children’s Сommission was created, and many orphanages and vocational schools were set up. A special task force watched train stations and railway tracks where the street children often congregated. They were apprehended, cleaned, fed, and finally assigned to an orphanage. By 1924, 280,000 children were living in orphanages.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox