The art of healing had always existed in Rus’ (as medieval Russia was known). The main tools of shamanic healers, however, were natural ingredients, as well as bathhouses, thanks to which the level of hygiene in Russia was higher than in European countries. Valuable information was passed on from Byzantium, which had preserved the knowledge of the wise men of antiquity and the East, while medicines came via the Silk Road.

With the advent of Christianity, an important role began to be played by hospitals at monasteries, where the local population was treated. In their libraries, many manuscripts, including medical ones, were stored, translated and revised.

But, the development of medical care in Rus’ was seriously hampered by the Mongol invasion. However, it proved possible to revive it, largely thanks to the experience and skills of foreigners who came to Russia to work for the local nobility.

German physicians appeared in Russia as early as the 15th century. The first of them were members of the retinue of Sophia Paleologue (Palaiologina), niece of the Byzantine Emperor and wife of Ivan III. Chronicles refer to a doctor “Anton Nemchin” (“Anton the German”), who was treated with great respect at the court of the sovereign. An unenviable fate, however, awaited the doctor. When a patient (a Tatar prince) died from medication prescribed by him, the hapless doctor was handed over to the angry family of the deceased and executed by the River Moskva - much to the consternation of other foreigners. The unfortunate doctor “was delivered to the relatives and put to the knife under the Moskvoretsky Bridge, to the horror of all the foreigners, so that renowned Aristotele [Fioravanti, an Italian architect and engineer active in Russia from 1475 - Ed.], wanted to leave Russia immediately”.

Vasili III

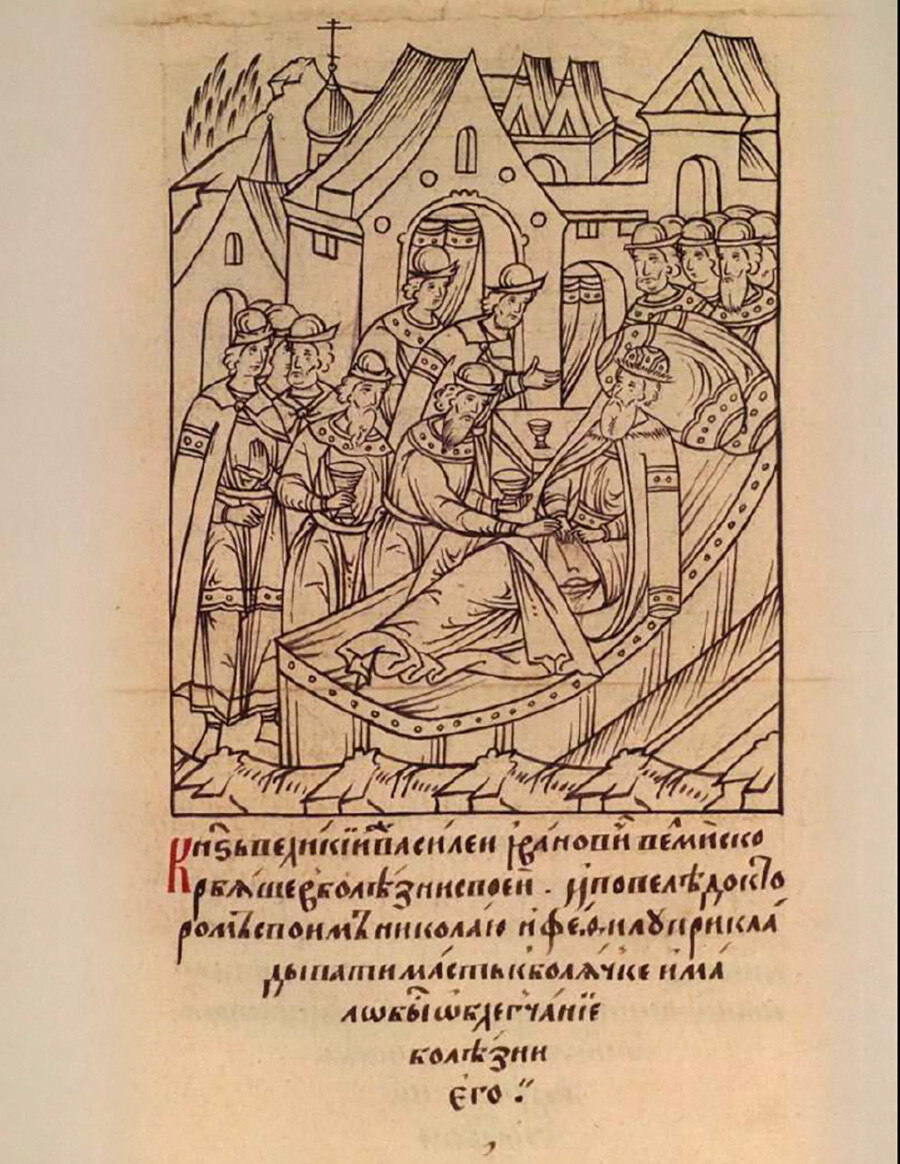

Public domainDespite this unhappy episode, Grand Prince Vasili III, son of Ivan III, also retained German doctors at court. One of them, Theophil (Marquart), a native of Lübeck, had been taken prisoner during one of the Lithuanian campaigns. The Prussian ruler twice asked Vasili to return the doctor to his homeland, but the Grand Prince valued Theophil so much that he kept refusing to do so.

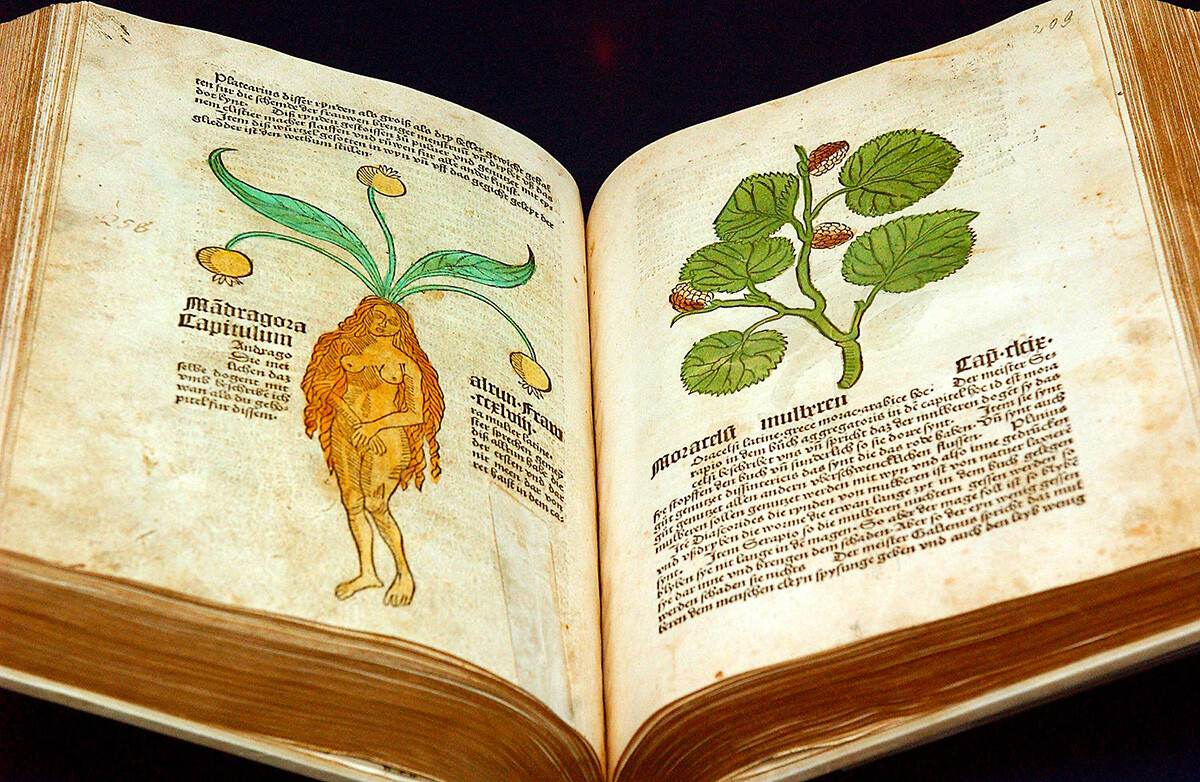

Niсolaus Bülow, another of the Grand Prince’s physicians from Lübeck, was well versed in many sciences and also served for a time as a translator. He translated into Old Russian ‘Gart der Gesundheit’ (The Garden of Health), one of the first books on medicinal herbs printed in Germany, which described the healing properties of plants and provided recommendations for the care of the sick. It was Theophil Marquart and Nicolaus Bülow who were entrusted with the treatment of Vasili III when he fell ill while hunting in 1533.

The Garden of Health

Legion MediaWell-known Russian historian Nikolay Karamzin describes a conversation between the dying Prince and Bülow: The sovereign calls the doctor “friend and brother” and asks whether he can be cured. When the doctor responds that he has no power to heal the dead, Vasili doesn’t get angry, but accepts his fate.

Grand Prince Vasili III and his doctors, Theophil and Niсolaus Bülow

Public domainThe practice of inviting English, Dutch and German doctors to Russia gradually gained popularity. Individuals whom today we would call “headhunters” were specially sent abroad to recruit foreigners. Among those who came to Russia were also opportunists - for instance, the Westphalian Eliseus Bomelius. He practiced magic and astrology and concocted poisons, for which he earned the popular nickname ‘evil sorcerer’. Chronicles accuse Bomelius of all sorts of sins: He was blamed for “leading the tsar away from the faith” and for the “tsar treating the Russian people with ferocity, while showing love towards the Germans”.

Viktor Vasnetsov. Portrait of Ivan the Terrible

Public domainUnder Vasili III’s son Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible), the first pharmacists appeared in Rus’ and, by the early 17th century, members of the medical profession were regulated by a special government agency - the Apothecaries Authority. It became clear at that time that medicines had to be made accessible to ordinary people as well and a pharmacy for “all ranks” was set up in Moscow in 1672. Two Germans were entrusted with this important undertaking - Johann Gutmensch and Christian Eichler. Prices were high, but the product range would have surprised even the seasoned traveler.

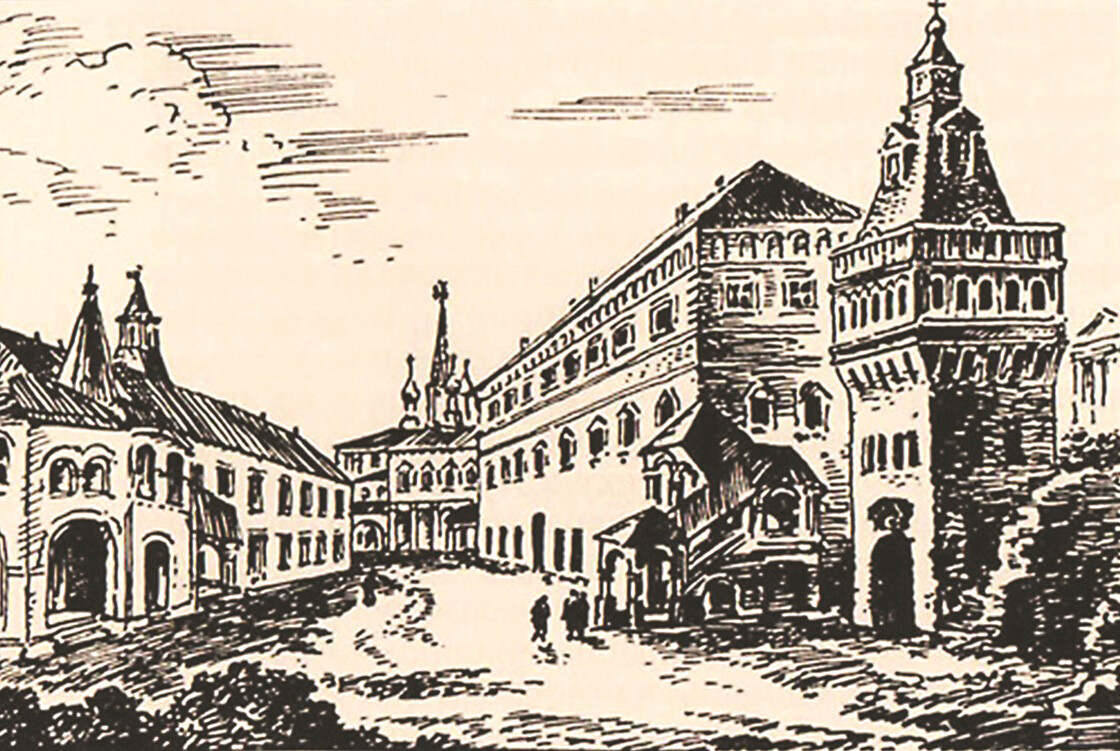

The Apothecaries Authority (circa 1600)

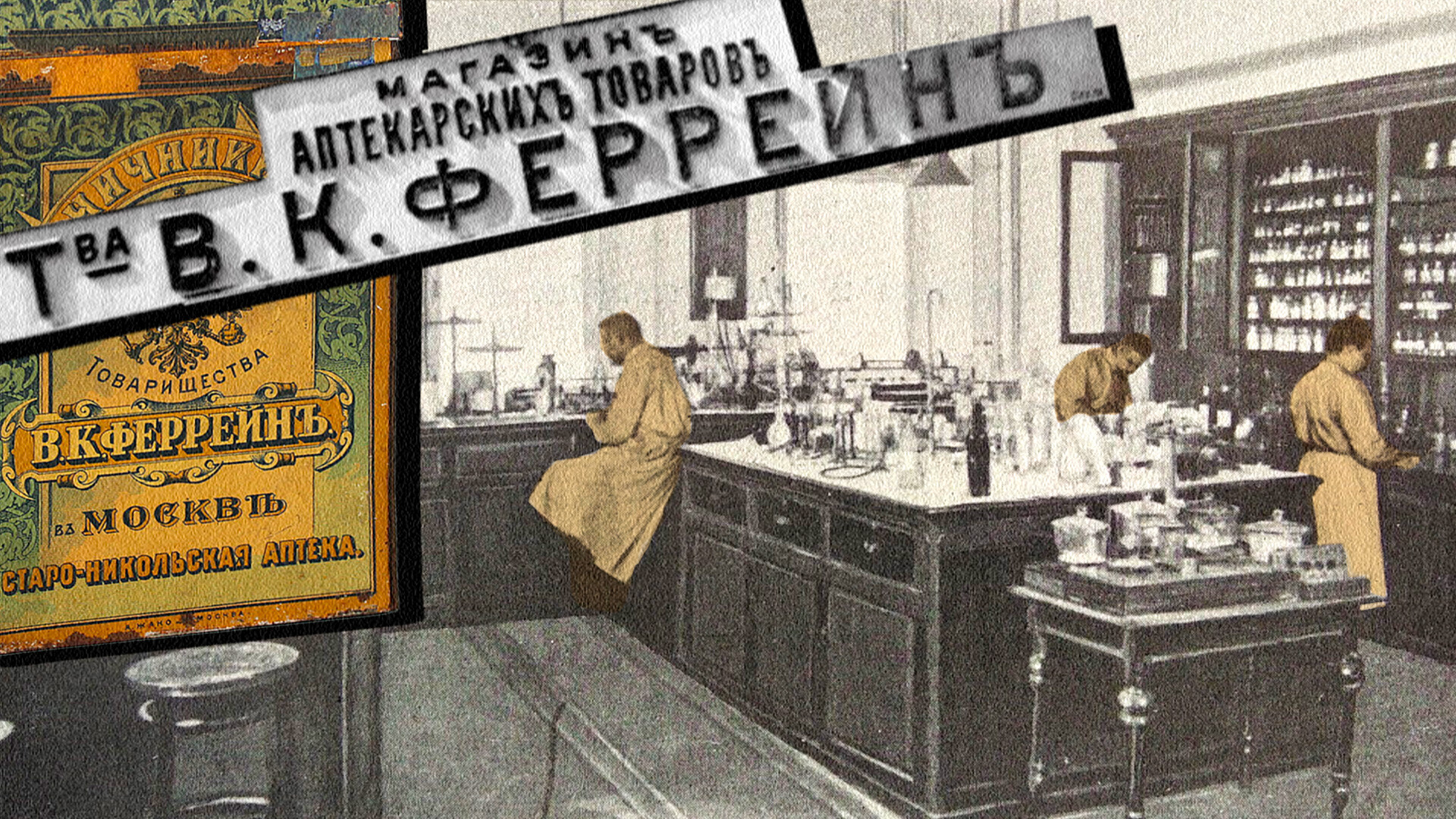

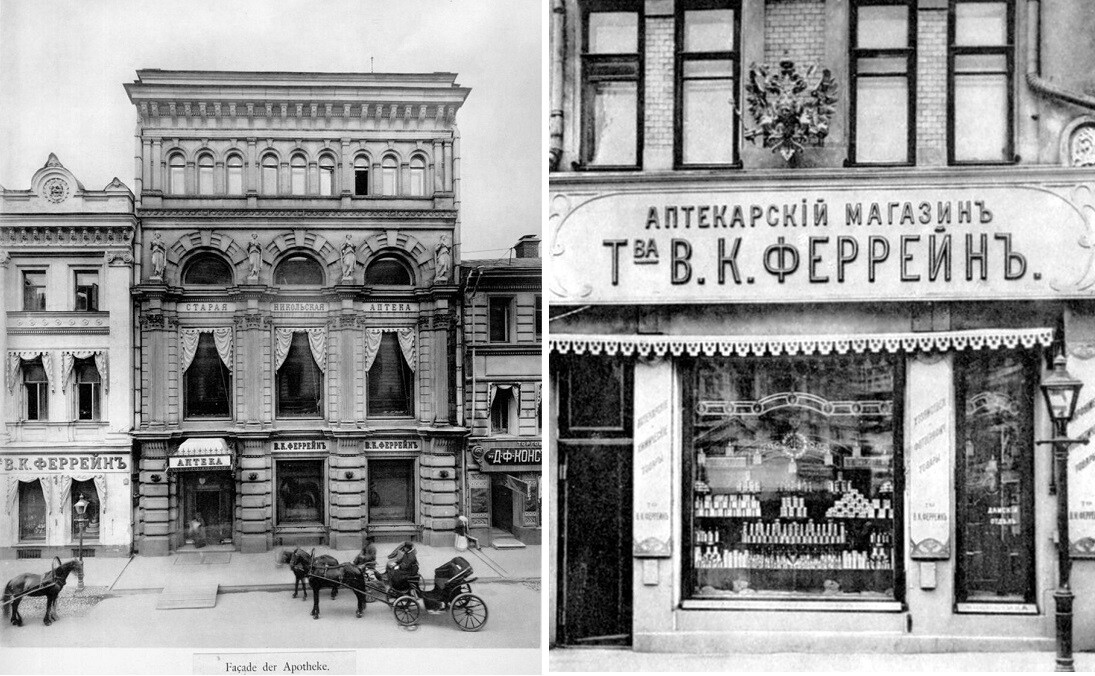

Public domainPrivate pharmacies also gradually began to appear and the first license to open one was, likewise, issued to a German - Johann Gottfried Gregorius. These establishments frequently changed owners and managers and, during their existence, saw numerous natives of Germany come and go. Whole dynasties of German pharmacists emerged - for instance, the Ferrein family ran Moscow’s largest pharmacy and, subsequently, founded one of Europe’s biggest pharmaceutical concerns, with five pharmacies, laboratories, a glass-blowing workshop, herb plantations and a chemical factory. The Ferreins also attracted fellow Germans to invest in their business.

The Ferreins pharmacy in Moscow

Public domainIt reached the point where almost all the owners and staff of Moscow’s pharmacies hailed from Germany and, in 50 St. Petersburg establishments, Germans made up 70-90 percent of the staff. Many pharmacists did not just sell medicines, but were also involved in constant research and, thus, developing the Russian pharmaceutical sector.

Professional societies, educational institutions and hospitals were opened with the assistance and support of Germans in Russia. Russia’s first medical association, the ‘Society of Surgeons’, consisted exclusively of Germans. And, by the mid-19th century, three out of five such organizations in St. Petersburg had been founded by native-born Germans.

The Medical Board in the building of the Main Pharmacy in St. Petersburg

Public domainThey published their scientific research in the form of collected writings or periodicals - for example, in the German-language ‘St. Petersburg Medical Newspaper’. Medical science also had Germans to thank for a large number of specialist publications in the Russian language: For example, the ‘Journal of Medical Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Science’ was founded thanks to the Poehl family of pharmacists. Their establishment additionally served as a hub for the editorial offices of many scientific and medical publications.

Another source of know-how and an engine of science was book publishing. The name of Johann Jakob Weitbrecht, who worked as head of the foreign literature bookshop at the Russian Academy of Sciences, deserves special mention. It was thanks to him that numerous scientific works on the properties of plants, obstetrics, pediatrics, sexually transmitted disease and even smallpox vaccination saw the light of day. Empress Catherine II attached great importance to inoculation against the latter disease and had herself inoculated less than a month after the publication of the relevant book.

Catherine II by J.B.Lampi

Kunsthistorisches Museum, ViennaIn 1786, Weitbrecht published a manual titled ‘Grundriss der Einrichtung der К. Medicinisch-chirurgischen Schule und einiger andern Hospitäler in St.-Petersburg’ (‘Plan of the facilities of the Imperial Medical-Surgical School and Some Other Hospitals in St. Petersburg’), written by the head of the Medical Collegium, Johann Heinrich von Kelchen. The school described in this work was, indeed, opened shortly afterwards: Its staff included several dozen German professors and four of its presidents were German. Their influence was so great that, for a long time, it was only possible to defend a dissertation in Latin or German. Among other things, the Medical Collegium was tasked with organizing medical care for the population, monitoring the work of the pharmacies and checking the proficiency of doctors, including those from abroad.

It is difficult to imagine a field of medicine in Russia in which individuals of German descent had not in some way had a hand in. Some terms from the German language are still employed by Russian doctors and the general public - the word ‘kurort’ (‘spa’), for instance, is still in very wide use.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox