Airport in 1958

Vsevolod Tarasevich/MAMM/MDFOnly a small number of Soviet people (diplomats, sailors and pilots, among others) were allowed to travel abroad for work. For everyone else, going beyond the ‘Iron Curtain’ was either completely impossible or a grueling quest. Citizens usually spent their vacations at the Soviet seaside or going on walking and hiking trips and learned about life in foreign countries from rare Western movies or from hearsay and word of mouth.

If, nevertheless, a good reason for traveling abroad could be found, people had to collect a whole bundle of authorizations, convince numerous boards and panels, as well as pass an interview at the local Communist Party committee. Owing to this selection system, people had to submit the required documents three to six months before their trip. And even having a valid reason did not guarantee that an individual would be allowed to travel abroad. For instance, one of the instructions for processing travel applications from aspiring tourists required that only those who “have sufficient life experience, are politically mature and irreproachable in their personal behavior and are able fully to live up to the honor and integrity expected of a Soviet citizen abroad” be considered for foreign travel.

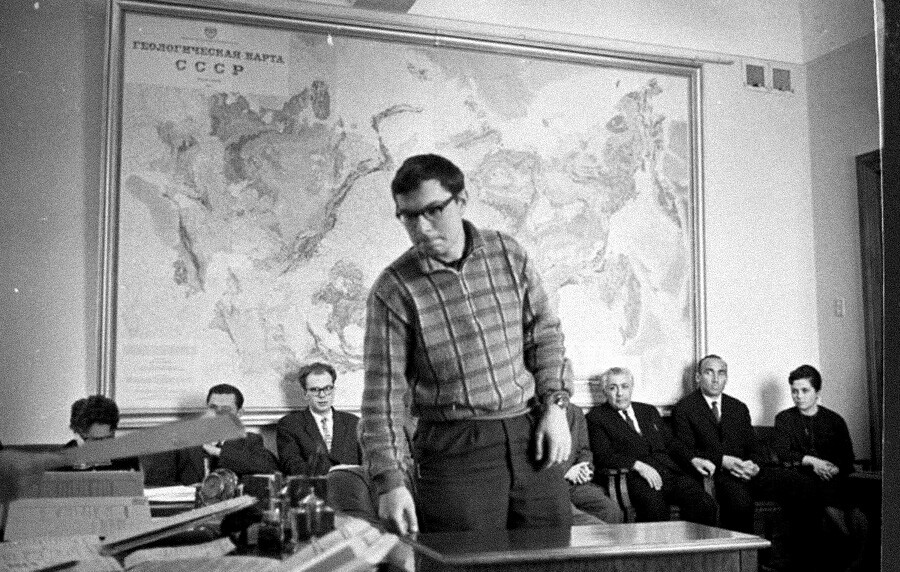

Placement system for geologists, 1963 - 1964

Vsevolod Tarasevich/MAMM/MDFOn the one hand, it was impossible in the Soviet Union for a graduate from a higher educational institution or vocational school to be left without a job. On the other hand, this imposed certain obligations on graduates. Only those with connections could immediately expect to get a position according to their qualifications and preferences. For everyone else, there was a placement system: A special panel decided where a graduate would work for the next three years. It could be an enterprise within the boundaries of the city where they lived or it could be somewhere on the outer edges of the Soviet Union, thousands of kilometers from their hometown. And a graduate could not refuse to go.

Soviet militia checks propiska

Valeriy Khristoforov/TASSThere was no freedom of movement in the Soviet Union: The state strictly controlled the movement of the population. It did this through the system known as propiska, which referred to the permit to reside in a given place that was stamped in a person’s passport. From 1960, living without a propiska for more than three days was regarded as a criminal offense and was punishable either by a year’s imprisonment or a fine amounting to one month’s salary.

So, if you dreamed of living somewhere other than where you were born, you could only move after getting permission from the authorities - and you had to provide compelling grounds. Such grounds could be to do with work, study or army service, for example. Losing your job, however, meant you lost your propiska, as well.

Unemployed people did not fit in with Soviet ideology. Everyone was expected to work and help build the Soviet state. From 1961, the Criminal Code had an article relating to tuneyadstvo (‘social parasitism’) under which people who had no job for four months (except for mothers with small children) were prosecuted. So called tuneyadtsy were sent for compulsory corrective labor to remote corners of the country for terms of up to five years. And, it was not just people without work and income that fell victim to this article of the law, but also individuals who did earn an income - but one that was not derived from work or was unofficial. Private taxi drivers, builders, musicians and so on were under constant threat of receiving a sentence.

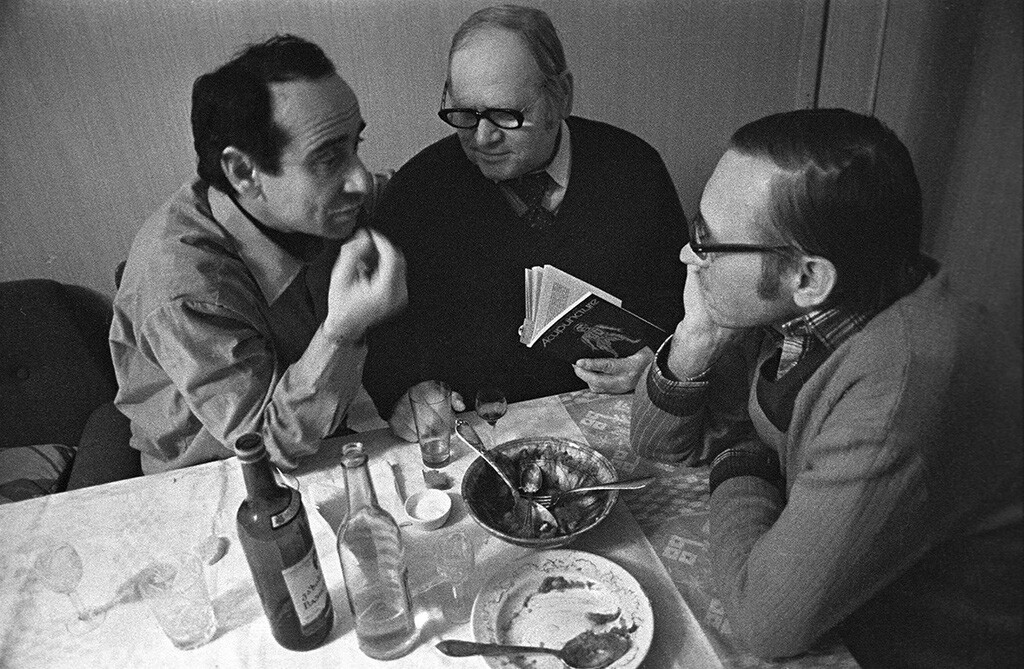

Kitchen discussion. 1970

Archive of Mikhail DashevskyAntisovetchik - literally, an “anti-Soviet person” - was the term used to describe those who did not agree with and criticized all of the actions of the authorities. Few people were locked up for public criticism, but even conversations around the kitchen table could give rise to charges of “anti-Soviet propaganda”," if they were reported by an informant family member or friend. Sentences of up to seven years were handed down for anti-Sovietism.

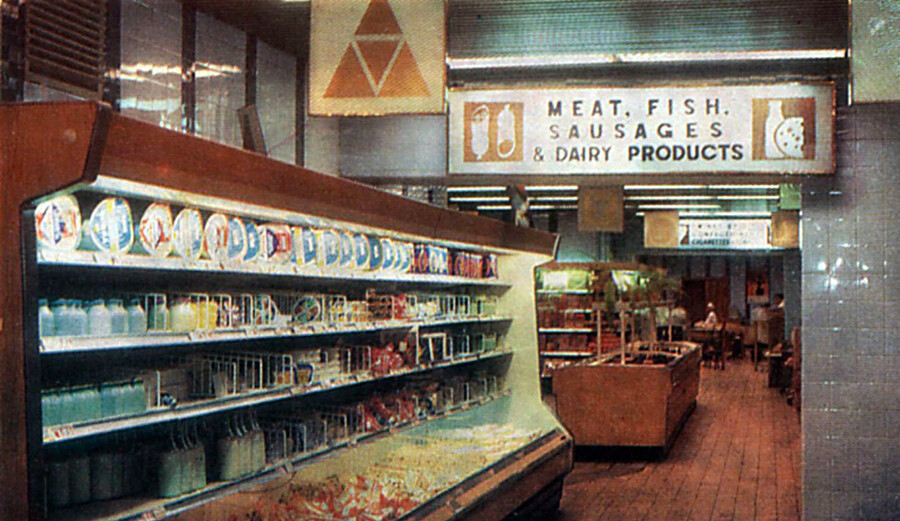

Beryozka shop inside, 1974

SazikovThe sale and purchase of foreign currency was the prerogative of the state. The country’s citizens were prohibited from holding foreign currency and, from 1937, this offense was equivalent to a crime against the state. If anyone had foreign cash left over after a foreign trip, it had to be exchanged for so-called bony (‘vouchers’) - special certificates that could be spent in the ‘Beryozka’ store chain. These stores, which were accessible to Soviet citizens who worked abroad and their family members (diplomatic and military personnel and technical specialists), sold American jeans, Japanese tape recorders, Italian boots and other kinds of defitsit - “goods in short supply”.

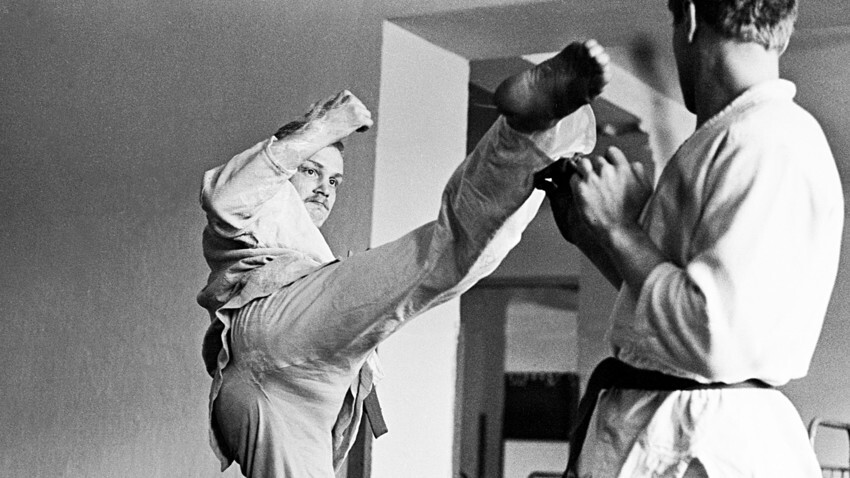

Karate became popular in the 1960s when a large number of movies depicting oriental martial arts appeared in cinemas. But, the Soviet version of karate had a distinctive aspect: It was popular among members of the criminal world and rank-and-file members of the police didn’t understand how they were supposed to match up to such trained fighters.

Karate also became dangerous in a political sense. During disorders in Poland, karatists even managed to break through a police cordon. The Kremlin did not want there to be such fighters in the USSR - and, in 1981, officially banned karate.

The same fate also befell bodybuilders - but for ideological reasons (muscle building simply for the sake of an eye-catching appearance was regarded as something anti-Soviet). Bodybuilders had to hide in basements and dodge the police. The ban was, however, lifted in 1987.

New settlers in the city of Naberezhny Chelny

Ye. Logvinov/TASSOne of the main planks of Soviet policy was the provision of housing for the working person. There were several ways of securing an apartment: for instance, getting a job in a company that built housing for its workers or giving birth to a child and joining the waiting line for improved accommodation. Housing was eventually given to practically everyone, but it was granted on the basis of a social tenancy for life.

Other people could be registered in such an apartment and it could be exchanged with another citizen (for a small surcharge). But, what could not be done was to sell, buy, gift or bequest such an apartment. Almost the entire housing inventory belonged to the state.

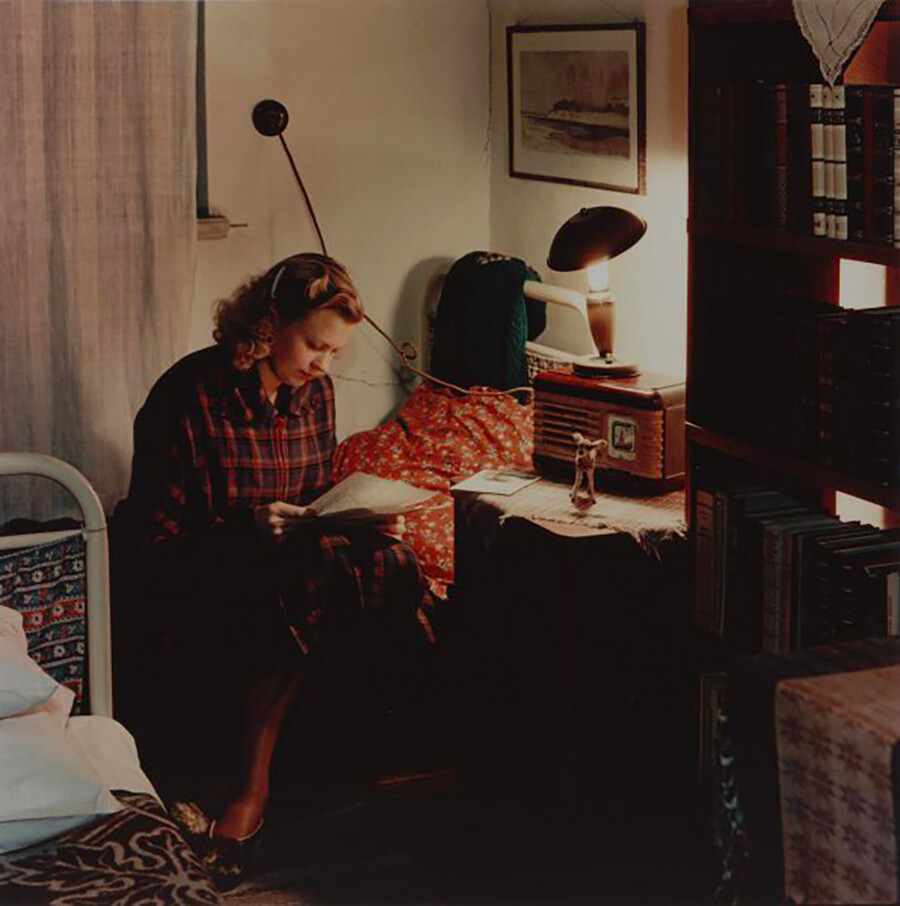

In the dormitory of the University of Tartu

Vsevolod Tarasevich/MAMM/MDFThe Soviet Union was one of the countries at which foreign radio broadcasts were purposefully directed. Some stations broadcast not just in Russian, but also in other languages of the nations of the USSR. But, the government had no time for these “hostile voices” and used to jam them. Around 1,400 jamming stations were built for this purpose, suppressing up to 40-60 percent of foreign broadcasts.

Every now and again, at times of political detente, the jamming was eased or suspended for a period. This happened in 1959, for instance, when the jamming of Voice of America was scaled down during a visit by General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev to the U.S.

“If you go and invent some kind of inflatable varieties of chewing gum, why do you have to peddle them around the whole world instead of peacefully blowing bubbles at home?” journalist Ilya Ehrenburg wrote indignantly in the ‘Culture and Life’ newspaper in 1947.

Chewing gum was subject to Soviet “sanctions” as a symbol of the “decadent West”, but, for this very reason, it was all the more desirable. Soviet authorities caved in after a tragedy: In 1975, members of the Canadian national ice hockey team decided to hand out chewing gum to children at Sokolniki Park in Moscow, which led to a crowd crush in which 21 people lost their lives. In 1976, chewing gum began to be produced in the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox