Despite being a very long distance from Israel geographically, almost from the moment it came into being, Russia found itself linked to Jews. When, in the 10th century, its ruler, Prince Vladimir, was choosing a faith for his people, he considered Judaism among other religions. This fact itself suggests that Russians had already experienced close contact with Jews. According to the ‘Primary Chronicle’ (also known as ‘The Tale of Bygone Years’), what, among other things, perplexed Vladimir about the story of the Jews was that they had been banished from their own land of Israel and scattered throughout foreign lands.

Ivan Eggink. Grand Prince Vladimir chooses faith, 1822

Public domainAmong Russia’s neighbors were the ancient Khazar people, whose elite had adopted Judaism. This fact gave rise to the hypothesis that all European Ashkenazi Jews are not descended from ancestors in Israel, but from semi-nomadic Turkic peoples from the Khazar Khaganate, who fled to Europe in the 10th century after their state disintegrated. Many Israeli historians, however, vehemently reject this theory.

After the expulsion of the Jews from numerous European states in the 14th century, they settled in the territory of Poland and Lithuania, as well as present-day Ukraine and Belarus (which bordered the Russia of that time). But, for a long period, they were not allowed to settle in Russian lands.

Ivan the Terrible was particularly strict in this respect - he banned Jews from entering the country altogether. This was mainly due to religious intolerance against people of a different faith. Converting to Orthodox Christianity was the only way of getting into Russia. If they did convert, former Jews were allowed to settle in Russia and were even paid for doing so.

During the rule of Peter the Great, the attitude to Jews changed. The tsar, who was favorably disposed to everything foreign and alien, even wooed several Polish Jews, granting them major government positions. For instance, Baron Peter Shafirov was an important diplomat (who maintained contacts with the King of Poland, among others) and was in charge of Russia’s entire postal service.

Immediately after Peter’s death, however, the negative attitude towards Jews returned. The tsar’s widow, the new Empress Catherine I, expelled them from the country. Peter’s daughter, Elizabeth, continued the same policy. Despite the fact that the Senate tried to convince her to at least temporarily let in Jewish merchants for trade fairs, her Edict of Expulsion included the following phrase: “I do not wish to obtain mercenary profit from the enemies of Christ.”

Jews in Odessa (then Russian Empire), 1876

John Buchan TelferA substantial Jewish population appeared in Russia in the late 18th century, when parts of Poland (where a considerable number of Ashkenazi Jews now lived) and Crimea, where the Crimean Jews - the Krymchaks and Karaims (local ethnic groups that had adopted Judaism) - had lived from ancient times, became part of the Russian Empire. For a brief period, Catherine the Great even allowed enterprising Polish Jews to live in various towns and cities, to trade and to engage in crafts and usury.

Very quickly, however, the proximity of even a small Jewish population provoked extreme resentment among Russians. Jews didn’t want to assimilate and were very religious (the Judaism that they practiced frightened the Orthodox Christians). Also, they simply annoyed Russians as competitors, being incredibly successful in commerce. There were complaints that Jews exploited hired labor and they were blamed for the miserable plight of everyone else.

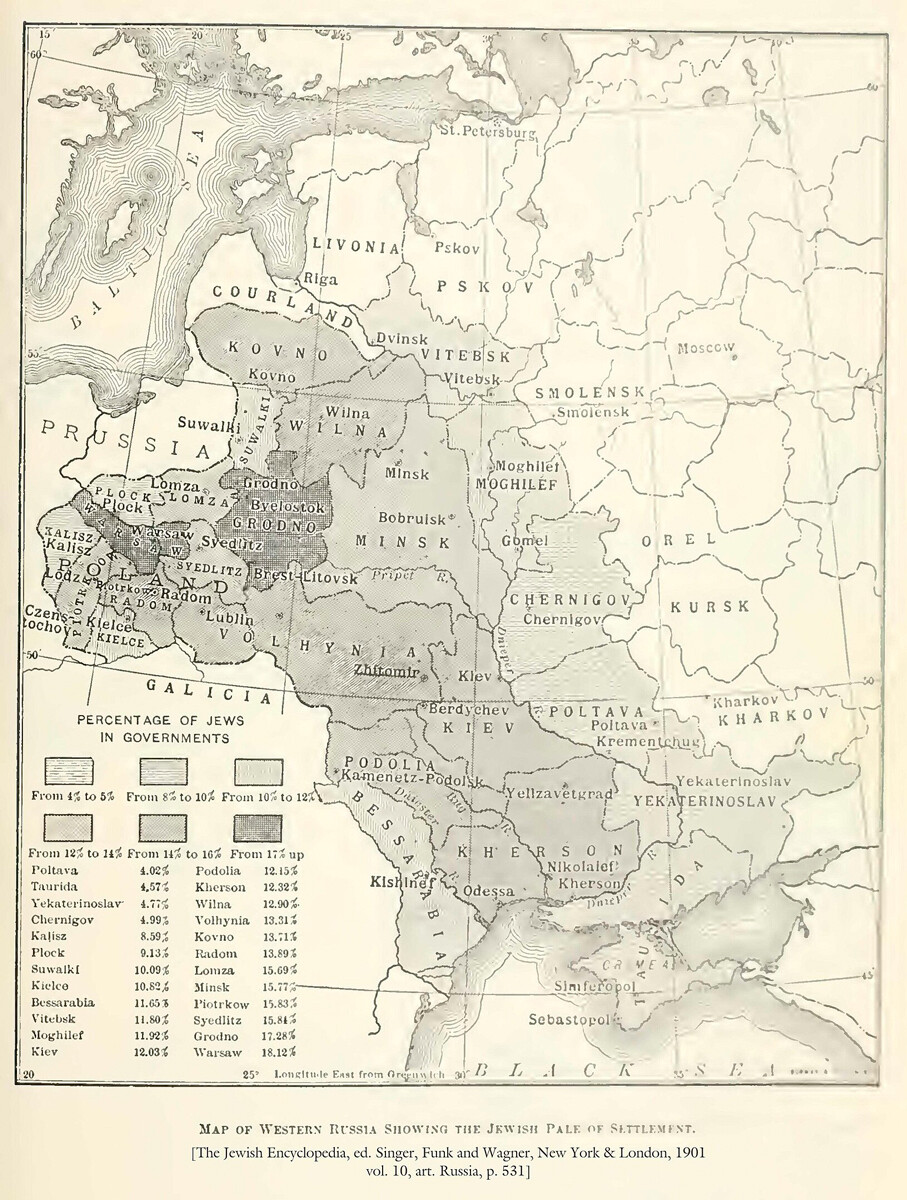

Map of Western Russia showing the Jewish Pale of Settlement (from the Jewish Encyclopedia). 1901

Public domainIn 1791, Catherine II issued an edict to the effect that Jews could only live in certain areas in the southwest of the empire and areas where they had lived when they became part of the empire. These were territories in present-day Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova.

The border of this area came to be called the ‘Pale of Settlement’. A considerable number of Jews spoke Yiddish and lived in ‘shtetls’ - small towns for the “lower middle classes”, i.e. the trade and artisan socioeconomic groups. For example, a multitude of Jews (including great Russian poet Joseph Brodsky) got their surname - Brodsky - from the Brody ‘shtetl’ in Poland (now in Ukraine).

Yehuda Pen. Divorce, 1907. From a series of paintings about life in the Pale of Settlement

Public domainEventually, by the late 19th century, about five million Jews lived in Russia. They were the fifth largest ethnic group in the country, with almost all of them living inside the ‘Pale of Settlement’ and enjoying limited rights. At the same time, Jews had a high birth rate and relatively decent living conditions. If in the first quarter of the 19th century, about half of the world’s Jewish population was living in the Russian Empire, by the end of the 19th century, the figure had reached 80 percent (the figures are cited in a book by Israeli historian Shlomo Sand).

It was possible, although very difficult, to move outside the ‘Pale of Settlement’. One had to acquire the status of merchant of the 1st guild, receive a higher education, serve a certain term in the army or be accredited to a particular craft guild. The list of professions that entitled individuals to settle outside the Pale was gradually expanded (doctors, pharmacists, etc.). At the same time, their access to schools and educational establishments was made difficult.

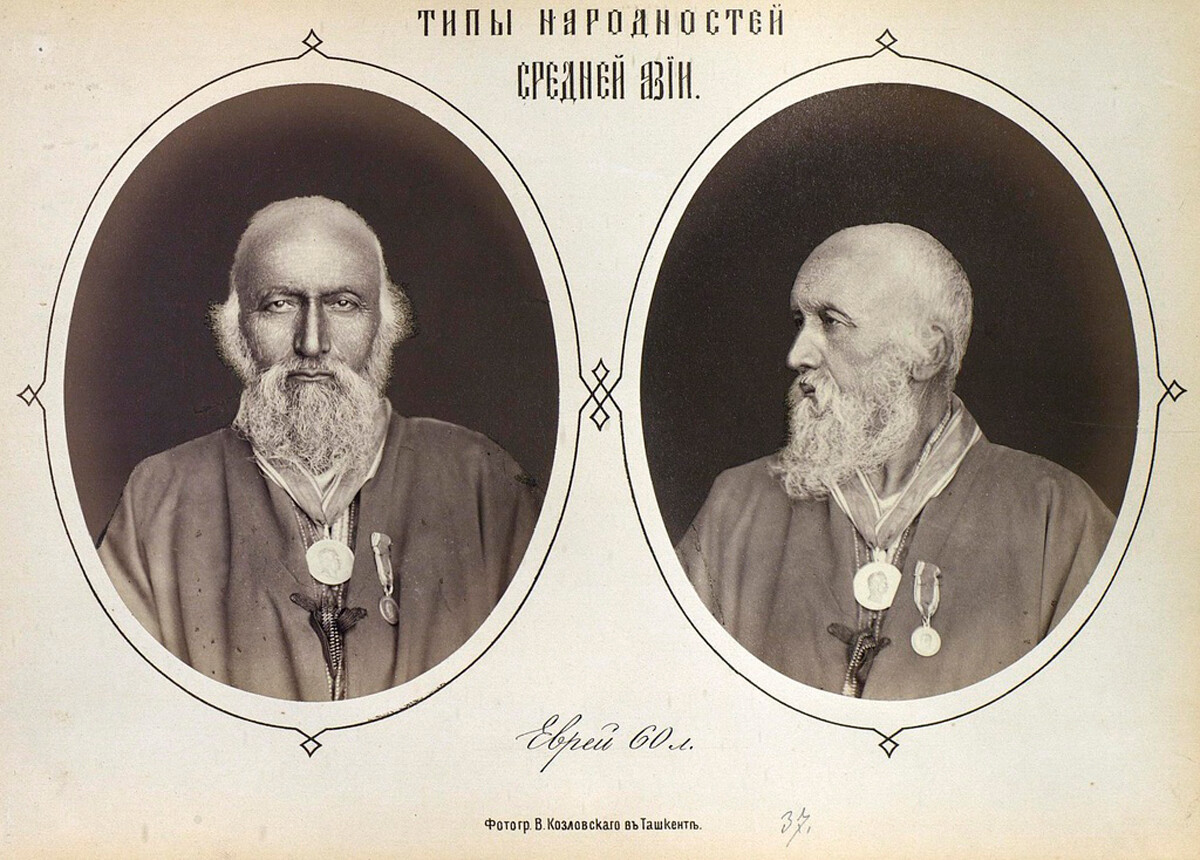

The rules were not quite as harsh for the Bukhara and Mountain Jews, who lived in the Caucasus and Central Asia, areas that were absorbed into the Empire after the introduction of the ‘Pale of Settlement’.

Portrait of a Jew, from the series "Types of Nationalities of Central Asia", 1876

Kunstkamera/russiainphoto.ruFor a long time, Jews in Moscow were only allowed to settle in one place (Glebovskoye Podvorye, where the first synagogue appeared at the end of the 19th century).

At the same time, Jews who converted to Christianity were granted all the rights enjoyed by other subjects of the Empire.

The policy of the authorities towards the Jews then underwent several changes. It was liberalized under Alexander I, who even released Jews in newly-acquired lands from military conscription obligations. Tsar Liberator Alexander II also eased the laws somewhat. For instance, he permitted Jewish communities to build synagogues outside the ‘Pale of Settlement’ and the latter literally sprouted like mushrooms in many towns and cities, including Central Russia, Moscow, St. Petersburg and also Siberia, where a large number of deportees and ex-convicts lived.

Jews talking in front of the shop, circa 1916

Public DomainMany Jews prospered greatly under Alexander II. For instance, the Günzburg banking family became nationally famous and they were even granted a barony. There were also major Jewish industrialists, such as the Brodsky sugar magnates.

Even at the end of the 19th century, Jews began to integrate strongly in the cultural life of the country and a large number of artists, musicians and other prominent figures were Jews. For instance, artist Isaac Levitan enrolled at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture - and was even exempted from tuition fees, because he was so talented. Subsequently, Levitan was to achieve tremendous success in Russian realist landscape painting.

Isaac Levitan. Over Eternal Peace, 1894

Tretyakov GalleryThe sculptor Mark Antokolsky, as well as, for instance, the pianist Anton Rubinstein, became widely known figures. And, at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, there were already dozens of such names, including artist Marc Chagall and dancer Ida Rubinstein. In the 20th century, a whole constellation of Jewish writers emerged – Isaac Babel, Ilya Ilf, Osip Mandelstam, Vasily Grossman, Joseph Brodsky and Mikhail Zhvanetsky, to name a few. They were all representatives of Russian culture, while writer Sholem Aleichem, who hailed from a Ukrainian shtetl, for instance, was a founder of Yiddish literature. It could also be noted that Alisa Rosenbaum, who was born into the family of a Jewish pharmacist from St. Petersburg, was more widely known as Ayn Rand, the American writer and author of the novel ‘Atlas Shrugged’.

Joseph Brodsky

Legion MediaAt the same time, there were already many Jews among revolutionary-minded young people, including members of the ‘Narodnaya Volya’ (‘People’s Will’) organization, which was behind the assassination of Alexander II in 1881.

Policies towards Jews were, once again, tightened under the reactionary Tsar Alexander III and anti-Jewish pogroms took place to which authorities effectively turned a blind eye. The tsar himself was personally regarded as anti-Semitic. A number of synagogues that had already managed to be built were closed and construction of new ones was banned. The ‘Pale of Settlement’ was again reinforced.

Nor did Nicholas II, who came to the throne in 1894, soften this policy towards the Jews, who began to emigrate en masse, because of ever more frequent pogroms. For instance, Golda Meir, who was later to become one of the founders of the State of Israel and the only female Israeli prime minister, left the Russian Empire along with her parents in 1903. She was born in Kiev and her father had even been granted the right to settle outside the ‘Pale of Settlement’.

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution itself is seen as having been in significant measure carried out by young and ambitious Jews desirous of gaining access to “social mobility”. The leaders and important names of the Revolution included a large number of Jews: Leon Trotsky (real name Bronstein), Grigory Zinoviev (Apfelbaum), Lev Kamenev (Rozenfeld) and Yakov Sverdlov.

Leon Trotsky, 1918

RijksmuseumThe large number of Jewish revolutionaries contributed to the emergence of the theory of a Jewish communist conspiracy, something that Nazi propagandists would later make much “play” of in equating Bolshevism and Communism with the Jews.

The revolution and Soviet power not only made it possible for Jews to settle where they wanted, but also, for the first time, to hold important positions in the state, to receive an education and to pursue any profession. At the same time, this unleashed something of a wave of anti-Semitism, including among opponents of the revolution. For instance, there was the well-known rampant Judaeophobia of the White general, Denikin, who effectively gave his blessing to pogroms in Southern Russia. Moreover, whereas previously anti-Semitism had been predominantly religious in character, now the “yids” began to be disliked on an everyday level (Jews were regarded as living better lives at the expense of others).

Stalin implemented a hardline nationalities policy, resettling ethnic groups, including the Jews. He planned to set up his own Soviet “Promised Land” in the Far East: This was how the Jewish Autonomous Oblast - a region of Russia to this day - came into being. The project, it has to be said, was a flop: Few people voluntarily wanted to go to such a distant and inhospitable territory.

A new twist in the spiral of state-sponsored anti-Semitism is also regarded as having occurred under Stalin - the ‘Doctors’ Plot’ (in which a group of medical specialists was accused of deliberate poisonings) is frequently referred to as the “last Jewish conspiracy”.

Rabbi Yakov Fishman during Rosh Hashanah in the Moscow Choral Synagogue, September 27, 1973

Museum of Jewish History in Russia/russiainphoto.ruThe Soviet Union was as vehement in battling Judaism as it was in battling other religions: Synagogues were closed down and their premises were put to use as warehouses or, at best, houses of culture.

Prior to the invasion by Nazi Germany, the USSR still had the world’s largest population of Jews – nearly five million in terms of permanent population and also up to half a million refugees. At the end of the war, less than half of them - for various reasons - remained. Some perished, some resettled to other territories and some were repatriated later to Israel.

Many Soviet Jews became atheists and broke with Jewish traditions. With the start of the thaw in the 1960s, many Jews in the USSR began to feel discriminated against. The word ‘Jew’ in the ‘Ethnicity’ field in Soviet passports was almost akin to a stigma and people felt uncomfortable articulating it. Many Jews were covertly barred from higher educational establishments and prevented from moving up the career ladder. In addition, there was also casual anti-Semitism. Many people began to conceal their background and even to forge their ID documents. (This, in particular, was why many later had problems with repatriation - they lacked the necessary documents confirming their ethnic background.)

Farewell of those leaving for Israel at Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport, 1970s

jewish-museum.ruThis situation led to the mass exodus of Jews to Israel, starting in the 1970s and continuing particularly intensively in the period of perestroika. Around 600,000 Jews emigrated at that time or were repatriated from the USSR. As it happens, more than one quarter of the population of Israel today consists of people who resettled from the USSR and are Russian speakers.

According to the 2020 Russian nationwide population census, more than 82,000 people who self-identify as Jews live in Russia today (but, given that the ‘Ethnicity’ field in passports has been dropped, it does not appear possible to verify this figure).

Believers attend an evening service at the Grand Choral Synagogue marking The Day of Salvation and Liberation of European Jews from the Nazis, 2021

Mikhail Tereshchenko/TASSAccording to information provided by the Russian Federation of Jewish Communities, there are Jewish communities in more than 100 Russian towns and cities, 45 of which have their own rabbinates. Additionally, more than 30 kosher restaurants and shops operate throughout the country, as well as a multitude of children’s schools, specialized publishing houses, media outlets and bookshops.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox