As the most prominent and powerful city of northwestern Rus in the Middle Ages, and being very popular with European merchants, Novgorod was unlike any other settlement in the lands of the Eastern Slavs during that era.

Traditionally, medieval Russian cities grew around the main fortress, which was the political and religious heart of the community. Novgorod, however, emerged from a union of three settlements inhabited by different Slavic tribes. For them, it became a “new city” – this is how “Novgorod” is literally translated from Russian (Novy – “new”, and gorod – “city”).

In the 14th and 15th centuries, during its heyday as a commercial and political power, the city of Novgorod was officially known as Gospodin Velikiy Novgorod – literally “The Great Master Novgorod”. The city was almost an empire, controlling vast lands from the Baltic Sea in the west to the Ural Mountains in the east, and from the White Sea in the north to the upper Volga in the south. After Kiev, it was the second most powerful city in medieval Rus.

Novgorod market in the 17th century

Apollinariy VasnetsovInternational commerce was the foundation of Novgorod's prosperity, which truly made it great and powerful. The local craftsmen – weavers and tanners, jewelers and glass blowers, potters and foundry workers, gunsmiths and locksmiths – were famous throughout the Russian lands. But Novgorod also did a brisk trade with Western Europe via the Baltic Sea trade routes.

By the end of the 13th century, merchants from the Hanseatic League developed strong trade relations with Novgorod. The Hanseatic League was the largest trade association of merchants from major German cities situated along the Baltic and North seas, but it also maintained four representative offices outside of the German-speaking world – in Novgorod, Bruges, Bergen and London.

Guests from over the sea, Nikolai Rerikh, 1901

Nikolai RerikhThe German merchants came to Novgorod to make wholesale purchases, and deals were concluded at the Hanseatic League's representative office. However, a merchant from any other Russian city couldn't enter the office's territory and make deals there.

European merchants were eager to come to Novgorod to sell prized luxury goods such as wine, expensive fabrics, ornamental stones, and precious metals. In return, Novgorod sold fine and precious furs such as squirrel, weasel, and sable. Novgorod also massively exported honey, leather, wax (which Europe needed to make church candles), and walrus ivory.

Velikiy Novgorod

Apollinariy VasnetsovNovgorod’s political system was unique among the myriad of city-states and principalities of medieval Rus; it was ruled by a small circle of boyar families that owned huge fiefdoms both near the city and in remote northern lands. The title of boyar in Novgorod was hereditary, a fact that distinguished the city from the rest of Russia, where the title of boyar usually was bestowed upon military commanders who were close to the Rurikid princes. The fact that Novgorod was ruled solely by locally-born aristocracy was actually a prominent feature in the principality’s unique form of republican government.

READ MORE: Who were the Russian boyars?

Unlike the boyars in the rest of the Russian lands, the boyars of Novgorod weren’t military commanders. Rather, they were locally-born landowners and high-profile international traders who also were proficient in politics. The supreme authority in Novgorod was the Veche, a kind of parliament that included the wealthiest and most influential men in the city. The upper part of the Veche included at least 300 boyars – 14th century German sources report that the main assembly in Novgorod was called the "300 golden belts".

The Veche met in public on the square near the central market, and its convocation was announced by the famous Veche bell, a symbol of Novgorod’s freedom and independence. The veche was not unique to Novgorod, however, and it was also a feature of the political system in other cities of medieval Rus until the time when Moscow began to solidify control over the other principalities to form a centralized Russian state. Only in Novgorod did the Veche exist up to the 15th century.

The Veche was so powerful that it elected and could even expel the prince; it also issued laws, declared war and made peace, established taxes and duties. Also, the members of the Veche chose a posadnik, who was the managerial head of the city. He monitored whether the prince fulfilled the terms of the agreement with the city, as well as managed Novgorod’s possessions and was responsible for law enforcement, the courts, and even signed diplomatic treaties. The prince of Novgorod had to represent the city to the other Russian lands and was responsible for the city’s defense.

The political life of Novgorodians, however, was not limited to the central Veche; ordinary Novgorodians also had the chance to participate in the city’s local street and district veches. The boyars used these meetings to promote their interests and fight against their opponents.

The city’s religious authorities enjoyed great freedom ever since the people of Novgorod were able to secure autonomy for their archbishop. From the beginning of the 12th century, the Kiev bishop (known as a “metropolitan”) basically rubber stamped whatever candidate was proposed by the Novgorodians for this position. The archbishop had his own regiment for protection, participated in diplomatic negotiations and put his official seal on international agreements.

Yaroslav the Wise, Nikolai Rerikh, 1941-1942

Nikolai RerikhRestriction of the rights of the princes began in Novgorod during the lifetime of Yaroslav the Wise (978 – 1054), who agreed to give special privileges to the Novgorod boyars vis-a-vis the prince in exchange for support in the struggle for control of Kiev. Novgorod did not develop a separate princely dynasty after the death of Yaroslav, because the city was at the source of the trade route "from the Varangians to the Greeks” and was closely connected with Kiev. When he died in 1054, Yaroslav the Wise bequeathed Kiev and Novgorod to his eldest son. As a result, the princely line that ruled Kiev usually chose a prince to rule in Novgorod, or Novgorod had the same prince as Kiev did.

In 1136, a rebellion in Novgorod led to the expulsion of the prince. From then on, the Novgorodians invited princes themselves and concluded a temporary agreement with them, according to which they could not interfere in the affairs of city management, change the highest officials and acquire lands on the outskirts of the Novgorod republic. In case of any violation of the agreement, the prince was expelled from the city, and the Veche selected a new candidate. Such changes more than once had a serious impact on the life of all the principalities of Rus.

Despite such treatment of the princes, all the major figures of Kievan Rus, who were the builders of the future united Russian state – from Vladimir the Great to Vladimir Monomakh – reigned in Novgorod before ascending the throne in Kiev. Symbolically, Novgorod was also the first place where Rurik reigned in Russia.

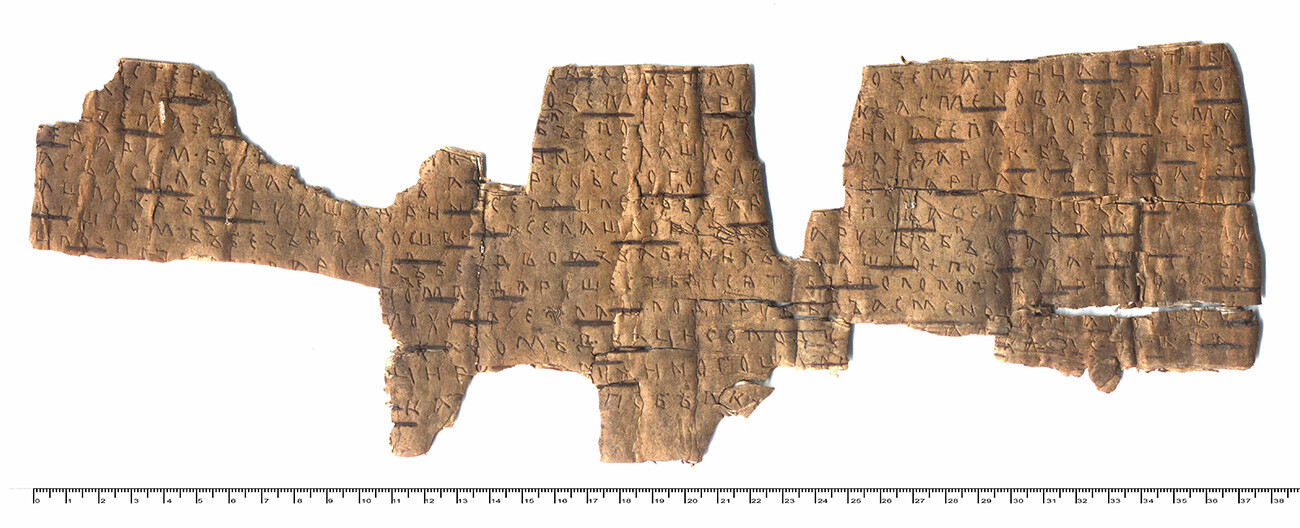

Birch bark letter #1

State Historical MuseumOn July 26, 1951, archaeological excavations in Novgorod found the first letter written on birch bark, with a discernible text carved on the surface. In total, more than 1100 such letters were found in Novgorod and about 100 in other cities of medieval Russia.

The analysis of Novgorod’s birch-bark letters allowed scholars to reconstruct the everyday life of the city and its inhabitants over the course of the 11th to the 15th centuries, which was the golden era of the Novgorod Republic.

The texts on birch bark testify to widespread literacy among the people of Novgorod who wrote to each other often and on a variety of matters, where they discussed household affairs, commercial transactions, as well as court decisions and simply the local gossip. Both men and women were literate, which was unheard of for Western Europe at this time.

READ MORE: How did single women survive in Tsarist Russia?

The birch-barks showed that the position of women in Novgorod society was quite prominent, and they conducted their own affairs, concluded commercial transactions, dispatched their husbands orders, as well as appeared in court, including on financial issues; and in general were actively engaged in economic activity.

Among the letters there were also touching declarations of love, such as the famous letter written by an unknown young woman in the 12th century: "I sent to you three times. What evil do you have against me that you did not come to me?" Another birch-bark letter contains one of the first records of Russian cursing.

Sadko, Ilya Repin, 1876

Ilya RepinNovgorod’s political structure and the nature of its economy created special cultural and real heroes. Unlike the characters of the Russian bylinas who spend their time lying on the stove and waiting for an opportunity to stand up for the fatherland, Novgorod's main hero, Sadko, who is a handsome man, as well as gusli player and merchant, is relentless in his pursuit of money and fame. He successfully swindles the sea tsar and wraps him around his finger, and once he is rich, he swears to buy up all Novgorod’s goods. In some versions of the legend he even succeeds.

Another atypical Novgorod hero, one not from a bylina but rather someone from real history, was the leader of the local resistance against Moscow. Marfa Boretskaya (or Marfa Posadnitsa because Marfa's second husband was a posadnik) came from an influential boyar family and owned vast tracts of land that were already in her family’s possession, as well as those lands that she inherited after the death of her first husband.

The taking away of the Novgorod Veche bell. Marfa Posadnitsa. 1889

Klavdiy LebedevWhen in the 15th century the Grand Prince of Moscow, Ivan III, began to unite the Russian lands by conquering other cities, Marfa entered into negotiations with the Lithuanian Grand Duke to propose a merger with Novgorod on the condition that it maintains its rights of autonomy.

READ MORE: How Russians executed... bells

Having learned about the negotiations, Ivan III declared war on Novgorod, and in 1478 the republic ceased to exist. As a sign of the abolition of Novgorod’s Veche, the famous bell was taken to Moscow, and the most promised townspeople were repressed. Marfa's lands were confiscated, and she herself soon died.

Nevertheless, while Novgorod has long disappeared from the map as an independent political entity, its legacy resonates today in the modern era. At the dawn of Russian history Novogorod accepted Rurik to reign, thereby laying the foundation of Russian statehood. Also, the city and its republican form of government showed that the path to rigid centralization and the absolute power of the Grand Prince was not the only possible political path for Russia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox