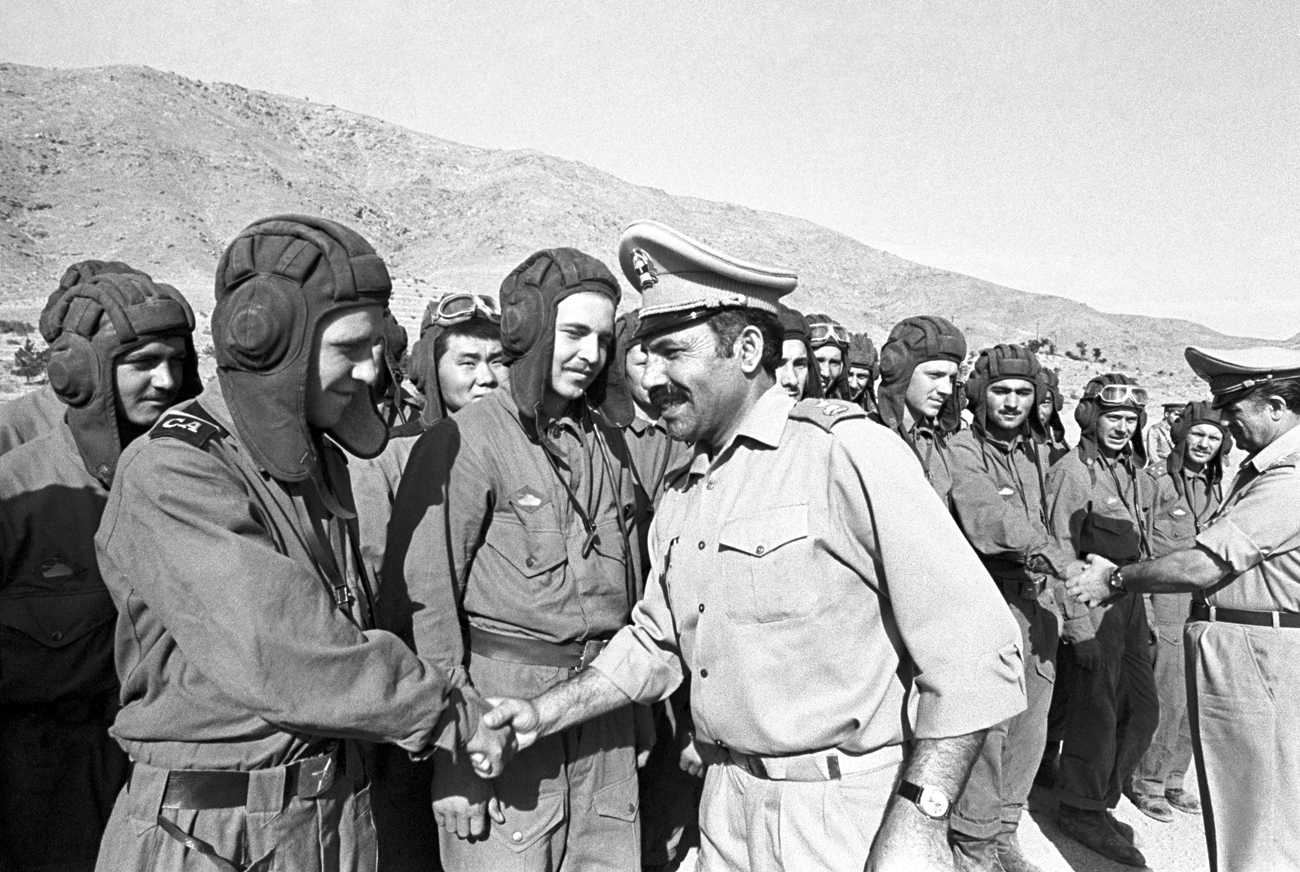

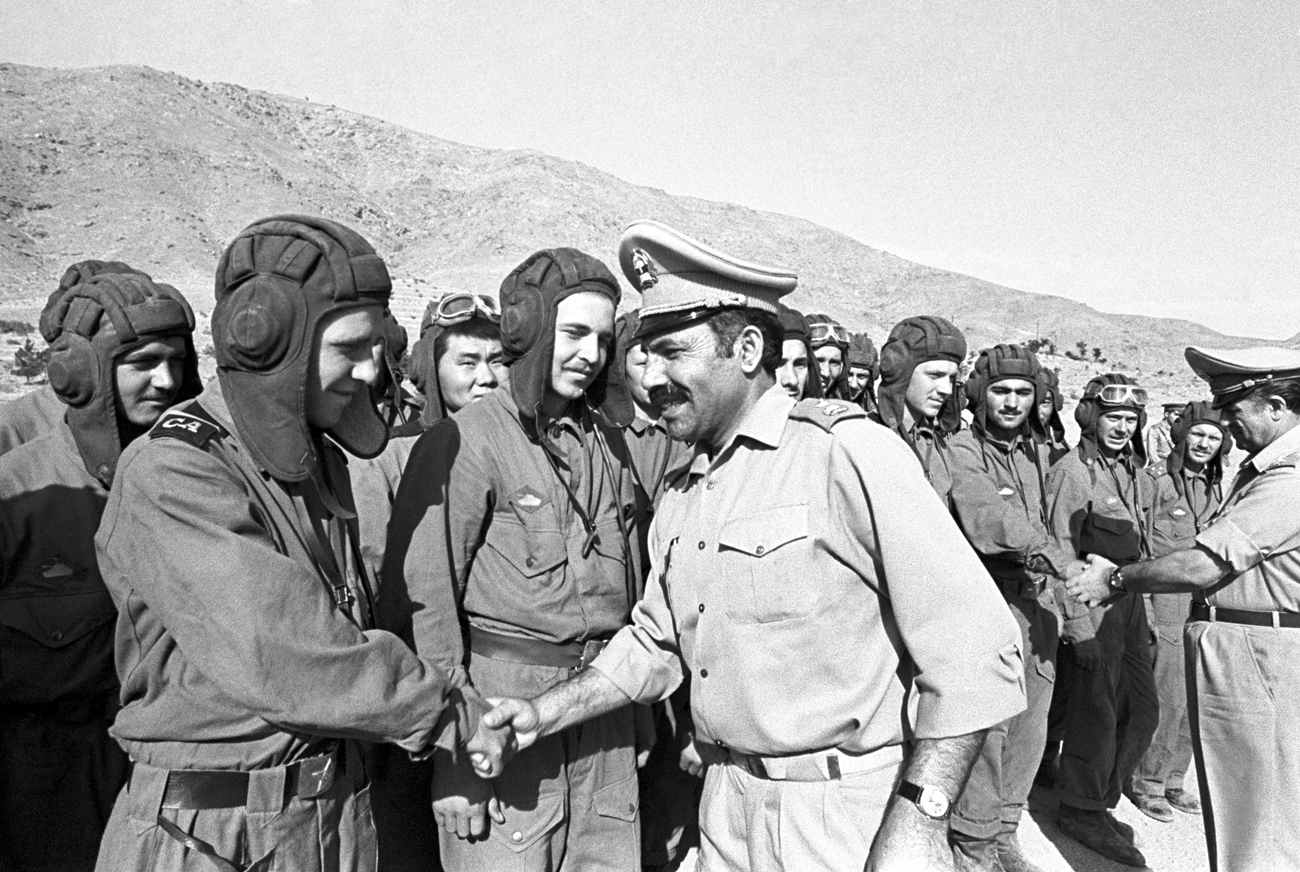

Soviet and Afghan soldiers’ farewell in 1980.

Georgy Nadezhdin/TASS Soviet and Afghan soldiers’ farewell in 1980. Source: Georgy Nadezhdin/TASS

Soviet and Afghan soldiers’ farewell in 1980. Source: Georgy Nadezhdin/TASS

There was no official Afghan War. There was no invasion of Afghanistan, as the western powers always accused. Instead, a limited contingent of Soviet troops was officially invited by the government of Afghanistan. The decision to send in Soviet troops was not an easy one. Nevertheless, the Politburo made the decision on December 12, 1979. One could possibly say, however, that the Soviet Union was lured into this conflict. According to former CIA Director Robert Gates, on July 3, 1979 President Jimmy Carter signed a secret order to fund anti-government forces in Afghanistan. Zbigniew Brzezinski later said, “We didn't push the Russians to intervene, but we knowingly increased the probability that they would.”

Afghanistan in geopolitical terms is a strategic place, and throughout its history many wars were fought over the country. In the 19th century, the Russian and British empires fought for control of Afghanistan in what historians call, “The Great Game.” The Afghan conflict from 1979-1989 was a continuation of that “game.” Riots and uprisings on the Soviet Union's southern border could not go ignored. Losing Afghanistan was not an option.

The Anglo-Saxon propaganda machine was working at full strength, creating an image of the USSR as the aggressor. The Afghan conflict allowed the West to turn the tables on the Soviet Union. By the end of the 1970s the USSR had enormous influence in the world vis-a-vis a battered and decaying America that just had been beaten in Vietnam. The American Olympic boycott did not go unanswered, and our athletes boycotted the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

The U.S. provided economic and military assistance to the Afghan opposition, supplying them with heavy weapons and providing military training to radical Islamic mujahedeen terror groups. The U.S. did not deny participation in this conflict. The third film in the epic “Rambo” movie series was made in 1988, and the hero, Sylvester Stallone, was this time fighting in Afghanistan. This ludicrous propaganda film even received a “Golden Raspberry,” and was recorded in the Guinness Book of Records as the film with the greatest amount of violence. The film concluded with the words, “This film is dedicated to the valiant people of Afghanistan.”

The Soviet Union spent about $2-3 billion annually on the war. As long as oil prices were high, the Kremlin could easily afford these expenditures. But starting in November 1980 oil prices declined drastically. In addition, Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign deprived the state of revenues from the sale of vodka. As revenues declined drastically, the USSR was hurtling toward economic collapse.

During the Afghan conflict, the Soviet Union found itself in a kind of cognitive dissonance. On one hand, everyone knew about Afghanistan, on the other hand people went about their lives. During the 1980 Olympics and the 12th World Festival of Youth and Students, the Soviet Union celebrated and rejoiced. Meanwhile, diabolical terror attacks were being prepared. As KGB General Philipp Bobkov later testified, “Long before the festival's opening, Afghan militants were trained in Pakistan by the CIA, and one year before the festival they were illegally sent to settle in the Soviet Union. They were provided with money, and waited to receive explosives, plastic bombs and weapons that they would then set off in crowded places (Luzhniki, Manezh Square, and etc). These actions were thwarted, thankfully.”

We all know about “Afghan syndrome,” about the thousands of broken lives, about veterans returning from war, useless and forgotten. The Afghan conflict created the “forgotten and betrayed soldier.” This image was atypical in Russian tradition. The Afghan conflict had undermined the morale of the Russian Army, and young men began to dodge the draft. The war inspired horror, and scary legends were spread about it. They sent soldiers there as punishment for misdeeds, and hazing flourished, which became the scourge of the modern army. At this time, the military profession ceased to be attractive. The “echo of Afghanistan” remains loud to this day.

First published in Russian by Russkaya Semyorka.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox