Russia, Moscow. Aerial view of Sokol District.

Anton Belitsky/Global Look Press“Where are all the houses?” says the average foreigner within the first 20 minutes of his/her first trip to Russia, before realizing shortly afterwards that those enormous, somber-looking concrete blocks they see all round them are the houses.

You see, the Russian notion of “suburbia” is slightly different to that of the West. As a country that was transformed into an urban society in a matter of decades, the Soviet Union housed its upwardly mobile peasants as cheaply as possible in communal apartments. As a result, the only fenced-off, gardened house the average Russian city-dweller stays in is the family dacha (unless he/she is a multi-millionaire with a suburban mansion). For most, a three-room apartment in a block of flats is deemed a perfectly acceptable place to settle down and raise a family.

An aerial view of houses in the Severnoye Tushino residential area in northwest Moscow.

Asya Dobrovolskaya/TASSOf course this is not always the case, but generally speaking, the smallest residential apartment blocks in Russia will have at least five floors (the least luxurious being the Khrushchev-era “pyatietazhki” built in the 1950s or 1960s). Even the sight of a massive courtyard full of five-story buildings can seem pretty ominous to Europeans – not to mention that it’s also common to find modern residential blocks as high as 20 stories.

“The average Russian apartment building would dominate the skyline of an English or Irish city, but here they’re just a drop in the ocean of thousands of lookalikes,” says Jack Dean, an Irish teacher.

Soviet flats were divvied out to citizens based on their work, so the average citizen had absolutely no say in the outer appearance of his/her block of flats. This created a culture of prioritizing interiors over exteriors. Russians, after all, are people who turn khrushchevki into chandelier-adorned castles.

Jack, however, has a rule of thumb: “I’ve figured out that if you give an apartment block a rating out of 10, you have to add 3 or 4 to that rating to get the quality of the apartments inside. Never underestimate a Russian’s redecorating ability.”

There’s a downside to this, though…

It’s often more economic to buy an older apartment in Russia, which means that the average resident has decades of other people’s history in their apartment they want to get rid of. Even if you buy a brand new apartment here, it’s likely to be completely bare. So either way, the outcome for the neighbors is the same: repairs, pounding and excessive drilling.

“You have to beat them at their own game,” Nick, an American writer, tells us. “If they’re drilling early in the morning, sometimes I’ll turn on heavy metal at full volume and they’ll get the message.” Drastic measures.

Word of warning: When house hunting in Russia, some foreigners get caught out by thinking their “3-room apartment” will have three bedrooms – this is not the case. In reality, the room count includes any living rooms and offices there, meaning it’s completely feasible for a 3-room flat to have just one bedroom (although many with kids or roommates will equally turn these rooms into bedrooms). Confusing, right?

The good news is that the kitchen is not counted as one of the rooms, so even a “1-room” apartment is usually not a classic “studio”, in the American sense of the word.

These thick metal units are quite a spectacle at first glance. “When I arrived in St. Petersburg and saw my door, I thought I was being brought to an interrogation room,” says Korean teacher Ching-Woo Park. “I opened it and inside was quite a nice apartment. What a relief.”

In actual fact, these doors make a lot of sense: With so many national holidays in Russia, most people are away at their dachas for much of the year, making thieving opportunities fairly predictable for burglars. Russians also have a tendency to store cash at home. The fortress therefore has to be as secure as possible, even if it’s at the expense of some outer beauty.

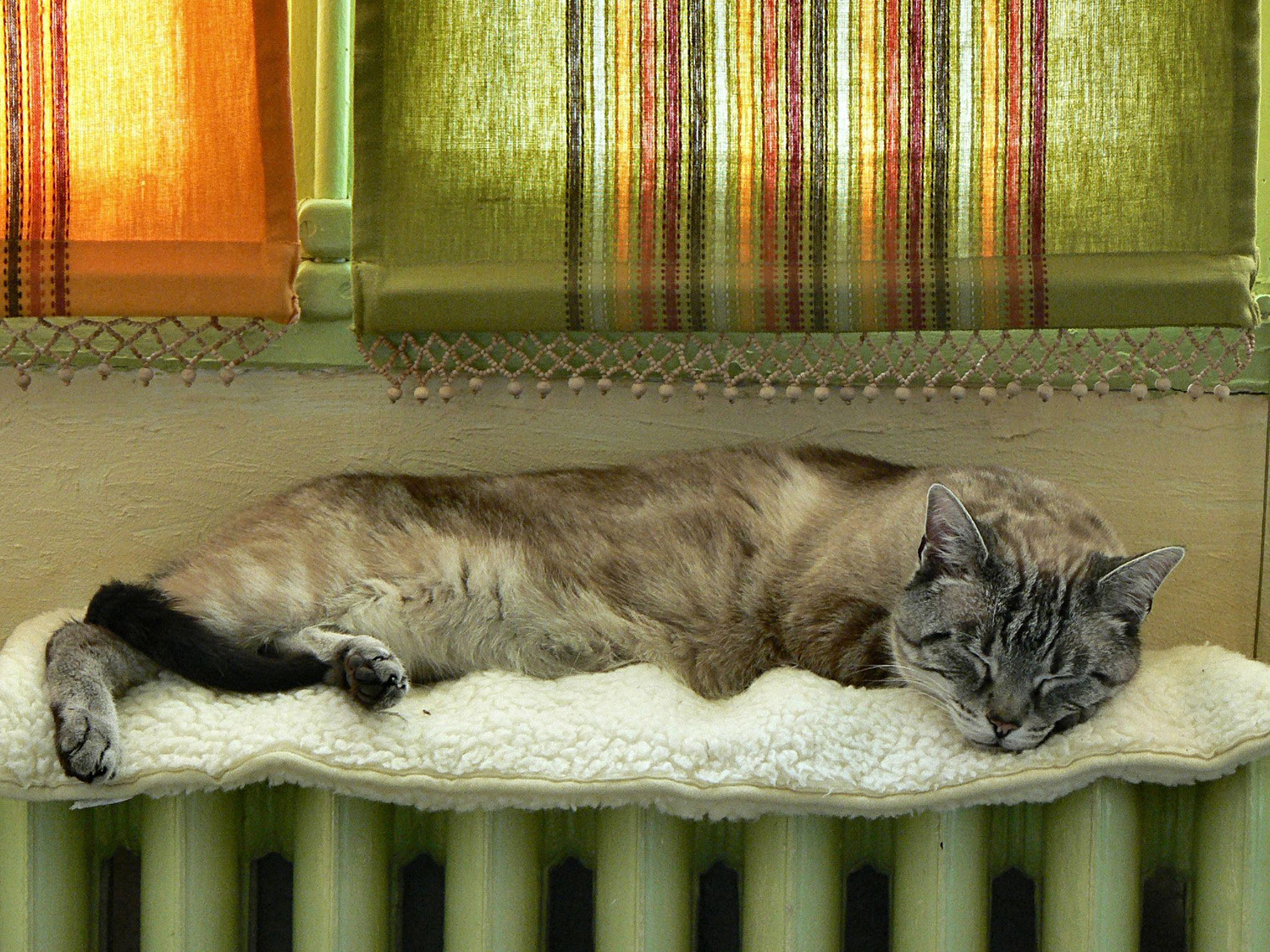

In Russia, heating is centralized via a few immense power plants – this means that an administrator will set the temperature in your flat. They usually put it at a sweltering temperature too, creating a discrepancy between indoors and out that takes quite some getting used to. It also means there are a couple of periods during the year (usually mid-October and early May) when it’s either chilly out, and the radiators aren’t on yet, or it’s balmy outdoors and the heating is still on.

“Moscow was getting warming during the spring and the heating was still on full blast, so my apartment was becoming unbearable,” says George Nelson, an editor from England. “I took a screwdriver and turned off the radiator in my bedroom. A few hours later I heard some angry knocks on my door. Turns out I had inadvertently turned off a few other radiators in my apartment block, and because Russians love to sweat it out at home, the office, and the sauna, I had to turn it back on - reluctantly.”

Gusinobrodsky solid domestic waste landfill, the Novosibirsk Region.

Alexandr Kryazhev/SputnikStudies indicate that more and more Russians are coming round to the notion of eco-friendliness. Indeed, President Putin recently signed a decree that will oblige councils to cooperate on waste separation as of 2019.

However, for now it’s much easier to use the communal serve-all skips in every courtyard than it is to recycle. Ironically, you usually need a car to access the recycling services currently available in Russia.

Been invited over to a Russian's house? You better know the apartment number and not just the host's name, says Lucia Bellinello from Italy.

"I buzz for the wrong apartment very often," she tells us, "and I end up looking for the right one for hours on end."

If you’ve got a three-room apartment with three or more people living there, where are you going to store your excess junk? Bear in mind that you’re unlikely to have a spare bedroom, while utility rooms are almost unheard of in Russian apartments. That leaves the balcony as the port of last call.

Residential balcony in Moscow's Alekseevsky District

Artem Geodakyan/TASSThat means that when the sun’s out, you’ll have to do your sunbathing elsewhere – that is, unless you fancy shifting your broken bike, your dad’s winter tires, and your sister’s spare skis first. Sorry.

Find out what else Russians leave on their balconies here.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox