Pyatigorsk chief rabbi Mikhael Khananashvili reading the Book of Esther during celebrations of the Jewish holiday of Purim in a synagogue.

Anton Podgaiko/TASSEvery spring, young rabbis and yeshiva students travel to different Russian towns and cities that have no rabbis. Their task is to conduct the Seder, a festive ritual meal that celebrates Passover, the feast of freedom commemorating the exodus from Egypt. The Seder takes place twice - on the first and the second night of Passover.

Members of a Jewish community during a ritual family meal on the Pesach Seder holiday in Veliky Novgorod.

Konstantin Chalabov/SputnikYes, rabbis can’t be found in every town – that’s a peculiarity of Russia’s Jewish community that distinguishes it from those in other countries.

“In New York, on one hand, there is a massive Orthodox Jewish community; on the other, a small

“Most Jews in Russia strayed far from Judaic traditions, and this trend is also recognizable in post-Communist countries such as Hungary or Poland; but it’s uncommon for Europe, where a Jewish community must be Orthodox, or otherwise it assimilates and dies out,” said Gorin, adding that 90 percent of members of Russian Jewish communities are non-religious people, often living in mixed marriages

Rabbi Borukh Gorin at the opening of the synagogue in Malakhovka near Moscow after the reconstruction.

Marina Lisceva/Sputnik

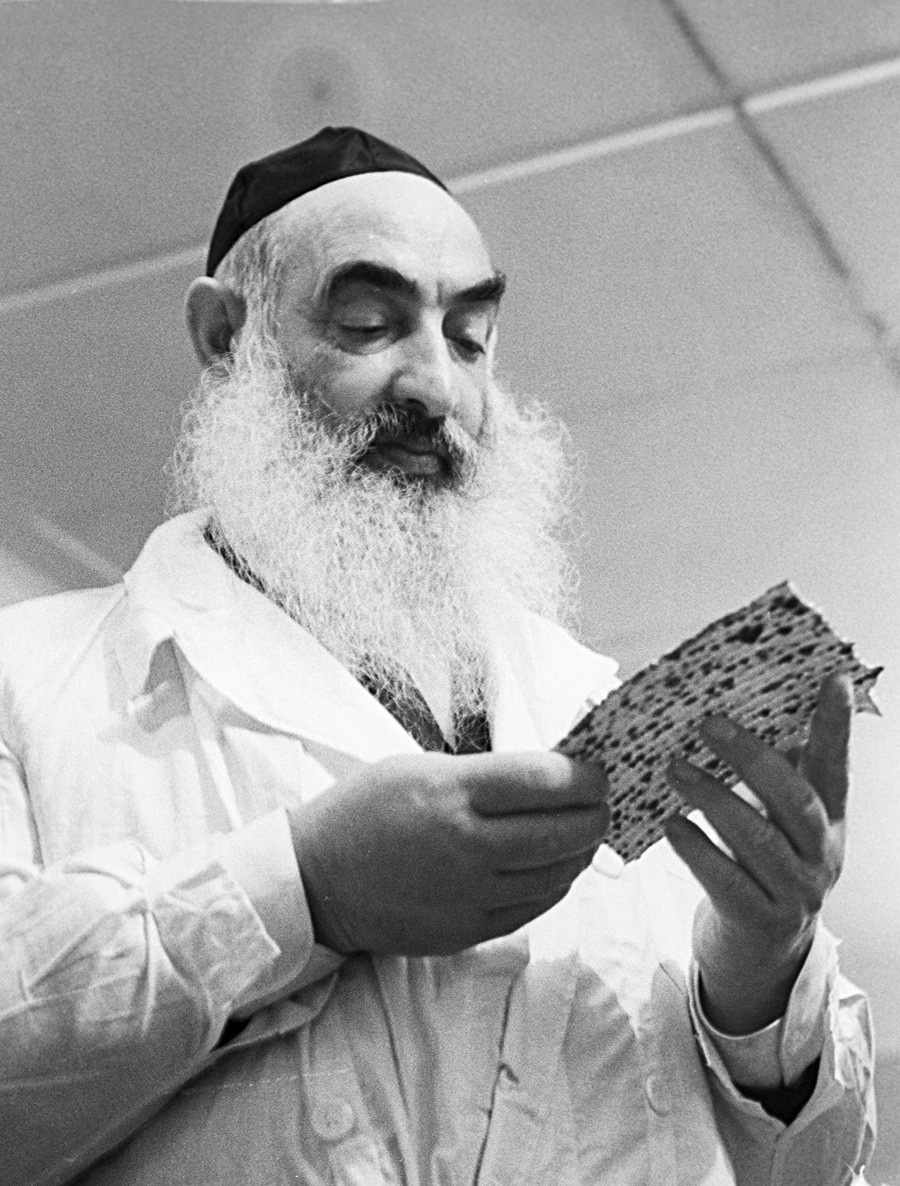

Rabbi Yehuda Leib Levin checking the matzoh industrially produced. 1968, Moscow.

Lev Ivanov/SputnikMany people even tried to conceal their Jewish roots, which again, prevented the formation of a community. Judaism, in general, was not welcome because it was a religion. There was no place in the new order for yeshivas, which were banned. As a result, Soviet Jews could not teach and learn Hebrew systematically. Even traditional Jewish matzo bread, essential for celebrating the Passover, was sold under the counter in Soviet times. Unsurprisingly, this was

“I think that if there had been no anti-Semitism in the USSR, then there would have been no Jews. We wouldn’t feel different from others,” says Anna Russ, a poet from Kazan (450 miles from Moscow). Borukh Gorin agrees: “Anti-Semitism prevented un-Orthodox Jews from assimilating during Soviet times.

“My great-great-grandmother perished in Kiev during the war, and not in

Stay or leave?

Jews in the USSR. Ceremonial wedding dance performed after the matrimony (hula).

Dmitryi Donskoy/Sputnik“Anti-Semitism has risen again in some European countries,” Gorin says. “But in Russia, surprisingly, it’s safer for Jews than almost anywhere else. In big cities, young people assimilate by themselves, not because of hardships. They just don’t feel like Jews, until they’re reminded of it in either a positive (like trips to Israel) or negative way.”

During the 1970s, over 100,000 Soviet Jews emigrated to Israel. After 1989, that figure was over 1 million. At the same time, organizations like

“Judaism came into our

Jews read the Torah as they attend celebrations of the Passover at the Moscow Choral Synagogue in Bolshoi Spasogolenishchevsky Lane, 2018.

Mikhail Tereshchenko/TASSGorin says that in the 1990s most Jewish people under 40 decided to stay in Russia – it was their older relatives who left. “This was a time of great opportunities here, young people understood that and stayed. The core of the contemporary Jewish community are people who were in their teens when the Union crumbled. They used their opportunities to the fullest.”

But Hillel and HaSochnut

Anna says she was afraid of emigrating because of the language: “I thought I’ll lose everything in a foreign culture. I didn’t even think of the Naale program. And now, I’m convincing my daughter to try it. I think you can’t be a Jew and not treat Judaism with the utmost respect.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox