Senior people play gorodki in the Leninsky District of Novosibirsk.

Alexandr Kryazhev/Sputnik

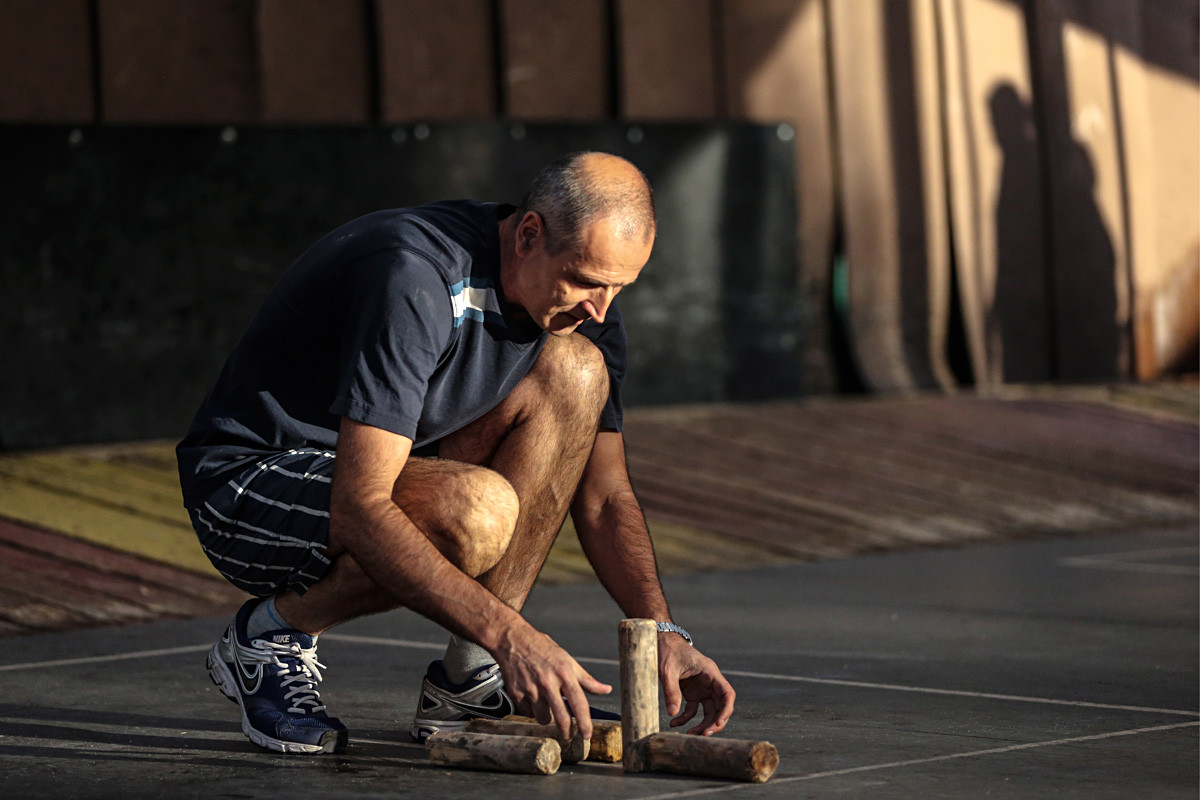

An athlete arranges a configuration during a Gorodki training session in Moscow's Kolomenskoye Park. Gorodki (townlets) is a Russian folk sports game.

Sergei Savostyanov/TASSLiterally translating as “townlets,” this incredibly fun stick-throwing game is something of a mix between horseshoes and boules. Originating from village life in the Russian Empire, this is as traditional as sport comes – it was mentioned in the Old Russian Chronicles and has been played by almost every historical Russian figure of note, from Peter I to Putin.

The concept behind gorodki is minimalist enough: remember that fairground game where you throw a ball at stacked cans and try to knock them down? It’s kind of like that, but on a bigger scale. In gorodki, you simply throw a big stick at the “townlets,” consisting of five cylindrical pins, from a distance of 13 meters and try to knock all of the pins out of their two by two meter square in as few throws as possible. The pins can even be arranged into differently-shaped “townlet” patterns such as a star, lobster, or airplane, to adjust the game’s level of difficulty.

Sound easy? Don’t get ahead of yourself just yet. There is one seriously mitigating rule to gorodki that makes it a tougher contest than it may seem at first glance: if the first landing of the stick so much as brushes the boundary of the two by two box, your “townlet” gets reset and you start from scratch. Pinpointing the stick perfectly inside the box is no easy feat, considering the size of the stick, and the fact that it’s being thrown horizontally.

On the plus side, one rule works massively in your favor: once you hit one of the pins, you get to try and clear the rest of them from a distance of just 6.5 meters. Swings and roundabouts.

It’s well-known that Russians are good ice hockey players. In fact, they’re so good that they moved on to a field hockey-cum-ice hockey-cum-footballing hybrid a long time ago.

Bandy, essentially ice hockey with a ball, has been a thing in Russia since the 10th century. Before iron skates were ever a thing, Russians were finding ways to fly around the ice for sport, and the game was played in most Russian villages by the 18th century. Of course, a few changes have been made since then: the number of players playing on one team has, thankfully, been limited to 11 (by most accounts, it used to be a bit of a free-for-all).

Indeed, many of the frameworks of football now apply to bandy: the tactics and formations are more or less the same, and unlike in ice hockey, the pitch is a similar size to a football field and there is no room for players to maneuver behind the goal.

Paced, open, and fiercely competitive, bandy is the sport for those who like ice hockey but in a longer, more grueling form.

Ever played baseball or rounders and got bored by all that standing around? Lapta is the game for you then: it’s pretty similar, but with less batting skill required, and therefore an added element of stealth and intensity.

The game dates back to pre-Christian times, and was a regular fixture of every public holiday (alongside mass fist fighting). As writer Alexander Kuprin wrote of lapta, “Deep breathing, attentiveness, resourcefulness, fast running, an accurate eye, and a hard shot are required, as well as an eternal confidence that you will not be defeated.”

What’s the setup to such a high-demanding game, we hear you ask? Well, you basically have to smack a ball with a cricket bat very tactically within a 30 meter by 70 meter grid. If the two runners are confident that they can then sprint the length of the pitch without one of the six pitchers catching the ball and running them out with it first, they go for it. If they make it, they win two points for their team. If they’re caught, it’s innings over, and the other team bats. And so it continues for one hour without breaks – whoever has the most points at the end wins. It’s best if you have a bit of pace for this one.

Ever wondered what a gorodki and fencing hybrid might look like? Of course you haven’t. Until now, that is.

As you’ve probably noticed, Russian sports all tend to involve very big sticks. Pekar (meaning “baker”) is no exception – in fact, a few big sticks are more or less all you need for pekar, aside from a used jar.

It works like this: the players throw their sticks at the jar. Once the jar has been hit, it’s a race between the stick-throwers, who try to gather their sticks back as quickly as possible, and the “baker,” who must put the jar back in its place and protect it from the other players’ attempts to sword fight their way back to the jar again.

The nice part of pekar is not that there’s no real winner.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox