“Pain pours off the screen like radioactive lava burning the floor. We’re so used to smirking at how American movies portray Russians that we overlooked the moment when they discerned things in us that we no longer can,” writes dramatist Nina Belenitskaya on Facebook.

She notes that the series hits home with Russian viewers (including the odd cyber pirate), who will definitely see it, even if illegally. But Belenitskaya is more curious to know what well-off people in well-off countries make of it.

Nina recalls that she was four years old in 1986 when the accident occurred. “People said the rain was radioactive. They said you mustn’t get caught in it because it’s corrosive. And going mushrooming was out of the question.”

Muscovite Andrey’s grandfather was a miner from Tula who was already retired when the accident happened and so not at the scene of the tragedy. Nevertheless, his relatives are still receiving benefits, since the radiation cloud spread as far as Tula. “I knew about the accident, of course, but for me Chernobyl had no particular emotive value. Still, after watching three episodes in a row, I didn’t sleep well, suffered from nightmares. I felt so dreadfully sorry for all those people and dogs.”

Many regret that such a hard-hitting series was not filmed in Russia. “In the three decades since the tragedy, no one in the post-Soviet space has ever given the event a proper screen treatment. As with the K-19 submarine tragedy or the space race between the USSR and the States, the world learns about Russian historical landmarks from English-language shows,” says editor Ilya.

There was in fact a Russian series in 2014 called Chernobyl. Exclusion Zone, but it was a mystical story about teenagers who visited the site in the present day, giving no clue about the disaster.

Sure, not everyone was pleased by the media buzz surrounding the series. Marusya Churai wrote on FB that she had read eyewitness accounts, watched documentaries, and been to Chernobyl herself three years ago. “HBO’s series is beautiful fiction, that’s all. Enough of all the hype.” Yet those who had no prior interest in the topic were deeply affected for the most part.

“My father was an ideological Soviet man and a military pilot. I even remember he had a copy of the Atheist Dictionary on his shelf. But over the years, he began to see the injustice and faults of the system, and criticized it a lot (mostly over dinner, of course). And I remember exactly how the accident was first announced on the radio. It was a curt message, but my father immediately realized the scale of the tragedy, and was very angry with the party and the officials. He believed they would cause the deaths of many people. My father died in June 1986, a couple of months after the accident, but he foresaw an awful lot. So when I watch the series, I see the same Soviet food that we had, the same clothes and hairstyles, everything is so detailed it’s creepy. It’s as if I stepped inside a time machine,” says accountant Elena.

“Even all the faces were Slavic, except perhaps for the shift supervisor, who looked more like a redneck. Sure, the vodka scenes were over the top. We don’t down glassfuls just for the hell of it,” believes manager Nikolay.

TV producer Yuri Golaydo has researched the topic extensively and filmed on location at Chernobyl, which is why he was doubly impressed (and horrified) by what he saw: “The level of detail is top drawer.”

Grigory Yavlinsky, leader of the political party Yabloko, also joined in the discussion. He says that all his friends and acquaintances with at least some know-how of nuclear clean-up operations went to Chernobyl. Most as volunteers. “The very highest level of human solidarity and dedication by any standards was displayed by the tens of thousands of people from all over the country who helped mitigate the consequences of the disaster.”

Facebookers write that the series is not just about the catastrophe, but about the Soviet Union as a whole, a view that Yavlinsky endorses. The main problem was not the danger (sometimes fatal), but the monstrous official lies. “The lack of freedom of speech and independent media led, among other things, to people celebrating the May holidays in 1986 as normal in Kiev and other cities inside the Chernobyl radiation zone.” It is this lack of freedom of speech that Yavlinsky sees as one of the drivers of the Soviet collapse just a few years later.

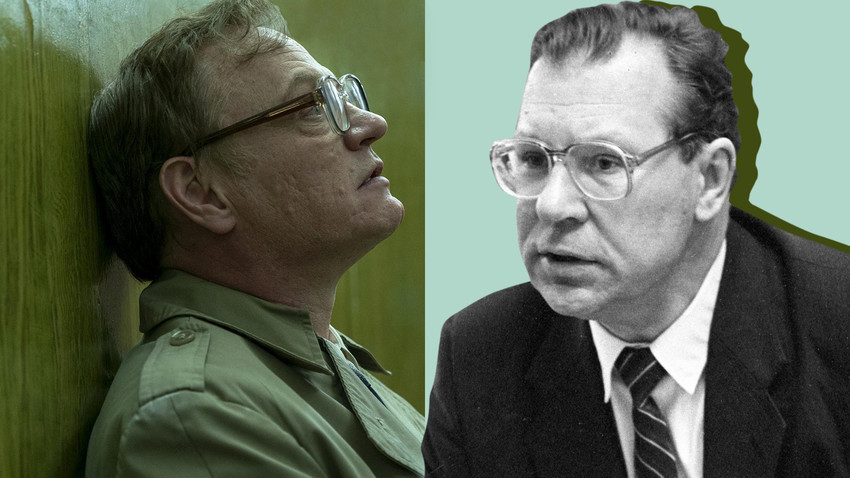

READ MORE: Who was Valery Legasov, the Soviet scientist that saved the world from Chernobyl?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox