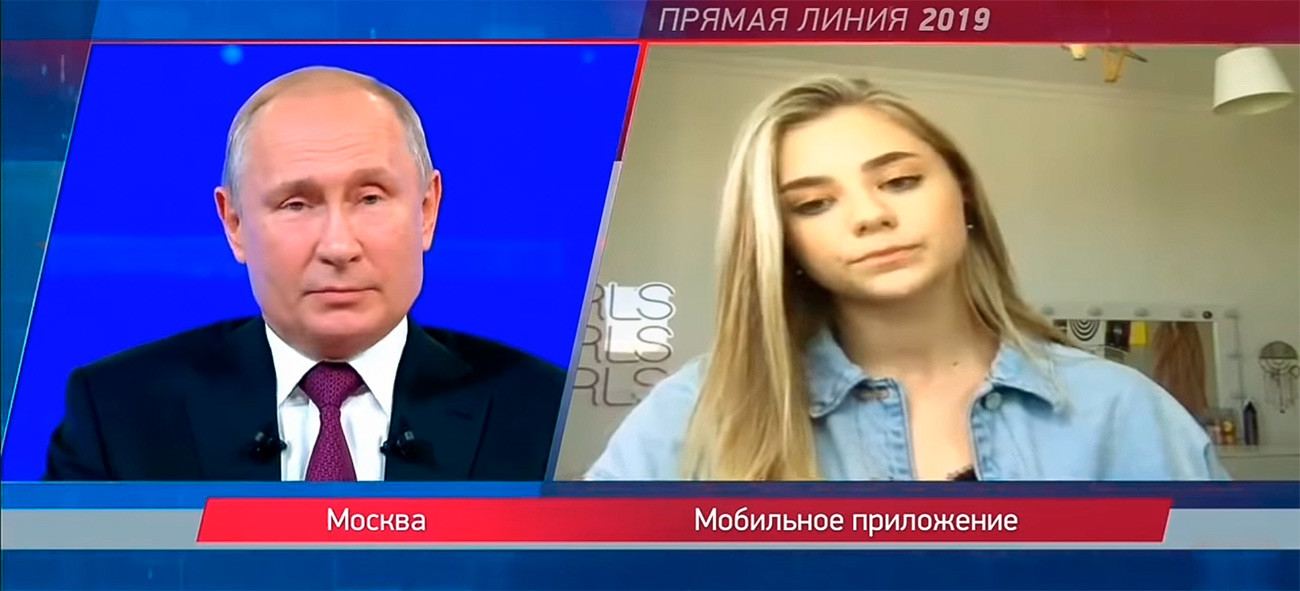

A young girl with a round face and blue eyes sits in her room in front of a screen. Behind her are an LED lamp that spells the word “Girls” and a small make-up table. Her expression betrays how nervous she is. Taking a deep breath, she clicks the mouse and, looking into the webcam, says:

“My name is Katya Adushkina, I’m a 15-year-old vlogger, I also enjoy music and dancing. But like all schoolchildren worldwide, I’m also concerned about environmental issues…”

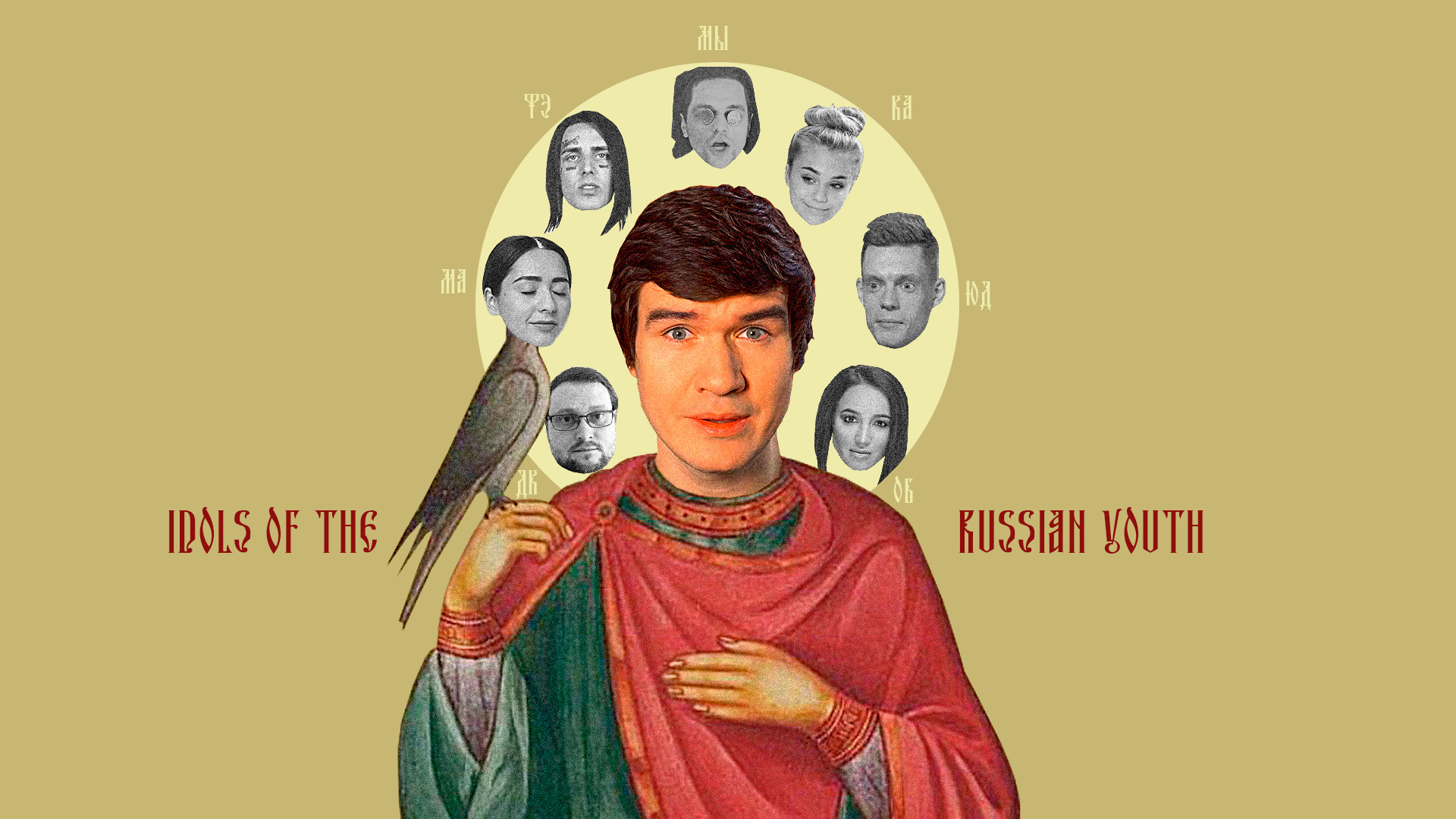

It’s a clip from Vladimir Putin’s annual “Direct Line” Q&A with the Russian public. For five years previous to getting the chance to probe the president about waste sorting, Adushkina made vlogs, uploaded various videos, and collected about 10 million followers on YouTube and Instagram. The popular Russian social network VKontakte counts numerous fake pages pretending to be her, since Katya is a role model for millions of Russian girls aged 10-15. But here’s the thing: Her question to the president is the first time she’s ever mentioned social issues.

“Feels a bit staged, the host immediately started praising her,” “It’s a PR stunt,” – after her exchange with Putin, Adushkina’s fan group is quickly flooded with negative comments.

But not everyone is so critical. Angelina, 12, from Krasnoarmeyskoye (700 km from Moscow), believes the question was right on the money. She genuinely has no idea what happens to the trash or how to sort it. A die-hard fan, she watches Adushkina’s videos every day and wants to be like her. Asked what she lacks compared with her idol, she replies without hesitation: Not as grown-up and less smiling.

In response to the question “Why does she want to be like her?”, Angelina shows a couple of her favorite videos by Adushkina where the famous vlogger demonstrates an “adult” way of life totally off-limits to a provincial girl from a small town – full of luxury clothes and cosmetics, vlogs from Spain, and videos in which she sings nonchalantly about how to “make up your lips so that boys’ eyes turn into coins.”

To somehow brighten up the dreariness of everyday life, Angelina and her friend Tanya regularly ask their parents for money for everything Adushkina advertises. Both dream of one thing – to grow up and rake in the online bucks like their idol.

More active followers go to fan meetings and even chat with owners of fake Katya pages, imagining that it’s really her. Someone somewhere sculpts her name out of chewing gum under a school desk, which some fans do not appreciate.

A slim brunette in jeans and black T-shirt wets her arms in a children’s pool, then crosses them as part of a strange dance. A pop song bleats out in the background: “Your words are water, that won’t do. You were good at divorcing, but I didn’t want to.”

It's an excerpt from a video by 16-year-old beginner model Arina Panteleeva on TikTok, another social network. She loves being photographed and painting her lips with red lipstick. Her video shows her taking part in a flash mob arranged by popular Russian singer and blogger Olga Buzova, who has 15 million Instagram subscribers. Three years ago, the singer divorced her soccer-player husband, since when almost all her songs have been about male betrayal and female power. Although the comments under her YouTube videos are overflowing with haters, she frequently advertises Moscow showrooms, chips, bank cards, etc., and fills concert halls across Russia with youngsters such as Arina.

“If you follow her, you notice she’s always working – filming, shows, concerts, etc. I have personal experience of shoots, and know how tough it is,” says Arina, adding that “even being 16, I couldn’t cope with all that.”

Another Buzova fan, Svetlana, is sure that Olga is showing the up-and-coming generation how to live without complexes and overcome all obstacles. Perhaps that’s why she is considered by some to be Russia’s most popular “folk” singer.

The social and cultural significance of what the likes of Buzova and Adushkina do is disputed. But if their lyrics and vlogs genuinely help girls from small towns to cope with life, does it really have to be high art?

In the city of Kuznetsk in Penza Region, the thermometer is reading 30 degrees Celsius. Out of a gray nine-story building emerges a group of guys in counterfeit Nike T-shirts and striped shorts, each holding a beer bottle. Together, they approach an eggplant-colored Lada. One of the guys – blond, tall, pumped – sits in the front seat and starts fiddling with the player. A minute later, the yard is drowned by the sound of loud bass, through which the words are barely discernible:

“Here’s my crew, they wanna eat

They want whores – I got it

That means they got it too, that’s my code of honor

I’m taking two, but it could be six”

The track is “Coin” by rapper LSP (real name Oleg). His videos have logged tens of millions of views on YouTube, and in April he held his first stadium concert. He used to write tracks with his friend Roma Anglichanin, before the latter’s death in summer 2017. Incidentally, the video for this song was blocked by the Russian regulator Roskomnadzor for allegedly promoting suicide. Yet an uploaded version still sits on YouTube, along with tracks by other popular Russian rappers: “I f...ed your chick,” “I love this little girl, she got a huge ass,” and others in a similar vein.

“The guys use these songs and their Lada to hook provincial chicks, who fall for their cheap bragging,” says LSP fan Dmitry Sorokin, 18, a resident of Kuznetsk.

But random sex and drug use, as glorified by Russian rappers, are aren’t the only methods, asserts 17-year-old budding photographer Vika, a bubbly blonde with a nose-piercing, who is also a fan of LSP.

“Me, for example, I don’t take drugs or sleep around,” she says. “The songs don’t promote that kind of lifestyle – they just tell about it, and sometimes mock it.”

Youth day. Kazan

Yegor Aleev/TASSWhat attracts her are the provocative lyrics, the beat and flow of the tracks. And she has a point. The words might seem horribly vulgar and mindless, but the next day I am unable to tear my ears away from them.

“If I want to think about something, I have a brain for that. But for dancing and chilling, music's what I need,” says Vika.

Alevtina is a quiet, somewhat fragile 15-year-old girl. She knows the capital city of every country in the world, loves swearing, and for some reason refers to herself in Russian using only masculine forms of words. Her mom, who works as a secretary, is convinced that her daughter should go to college and train as an accountant or a chef. Alevtina herself wants to study abroad, but doesn’t know where or what.

She is often to be found at home reading Agatha Christie or on her laptop, most likely watching a Let’s Play (LP) on Twitch or YouTube.

“Kuplinov is the best LPer out there,” she says, and shows a video of his. In it, a chubby 30-year-old man sits at a gaming computer, eyes rolling, mouth wide open.

His YouTube channel has picked up 7 million subscribers, and counting. In one of his most popular videos (more than 8 million views), he walks through a game in which nurses need to be undressed. Kuplinov manages to do it by asking the cartoon nurse to open a window, whereupon a bird flies in and poops on her, after which she is forced to undress.

“There we go. What a babe!” says the LPer.

“He’s got a really keen sense of humor. He can make even the dullest game fun to watch,” says Alevtina.

LPs and streams let people know if a game is worth buying, so many developers make money thanks to streamers, she is sure.

“Streams also give you tips and tricks to try yourself,” she continues, and disappears once again behind the laptop screen.

A guy in a red jacket stands in a snowy street talking about his winter outfit: heat-holding socks, special boots, two layers of thermal underwear, waterproof pants, puffer jacket with hood, scarf, hat, and mittens.

“This gear would do for Antarctica,” he says. “If it’s cold for us, what on earth was it like for gulag prisoners? Their clothes were totally different.”

This is a clip from a documentary by reporter Yuri Dud entitled “Kolyma – The Birthplace of Our Fear,” which has gathered 15 million+ views on YouTube. In the two-hour film, he talks about the harsh life in modern Kolyma (10,000 km from Moscow!), and the even harsher one endured by the mostly innocent prisoners sent there under Stalin.

“Almost half of all young people aged 12-24 have never heard of the Stalinist purges. We took it as a challenge,” explains Dud against a backdrop of winter landscapes.

“It’s time to stop defending Stalin. This film is quite emotional for the viewer,” says Sergey Basov, a 17-year-old schoolboy from Khabarovsk. He smokes cigarettes, wears his hair long, and listens to rap and rock. After watching the film, he delivers a conclusive verdict on Stalin: “Asshole.”

Other young fans of Dud agree. They watch not only his films about the Stalinist purges and the first rock festival in the Soviet Union, but also his interviews with popular musicians, politicians, directors, and bloggers, where the questions range from the topical “How much do you earn?” to the tactful “Do you masturbate?”

For Sergey and thousands of other youths, Yury is pretty much the only “honest journalist not afraid to talk about things that matter to young people.”

Another popular Russian blogger, BadComedian, is also loved for his fearlessness. He makes critical reviews of Russian movies, often financed by the government.

After a negative review of Beyond the Edge, the studio that made it, Kinodanz, filed a lawsuit against the blogger for copyright infringement. Later, Olga Lyubimova, head of the Department of Cinematography under the Russian Ministry of Culture, commenting on the court proceedings, stated that Russia lacked good, constructive film critics. Shortly afterwards, Kinodanz withdrew the lawsuit.

For 16-year-old Egor from Rostov-on-Don, BadComedian’s review of Beyond the Edge was enough to put him off seeing it.

“The review told me the film was poorly shot, so I lost interest,” he explains.

After chatting to teenagers, you start to realize that inside their smartphones, rappers and bloggers compete for space with popular reporters offering soul-searching videos about falling in love (no surprise there), the scourge of domestic violence, and self-acceptance.

All of this, including pop songs, travel tips, and LPs, helps them escape personal problems, build confidence, and strive for a better life. In the final analysis, it helps them know that they are not alone, that there is nothing wrong with them, and that they have the right to express their view, be it in the form of an hour-long review or a three-minute vocal outpouring.

“We like anyone who’s not afraid to talk about what’s bugging them, no matter how they do it. We enjoy listening to them, because it’s their truth. And ours,” says Vika (the LSP fan) about her idols. The others agree with her.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox