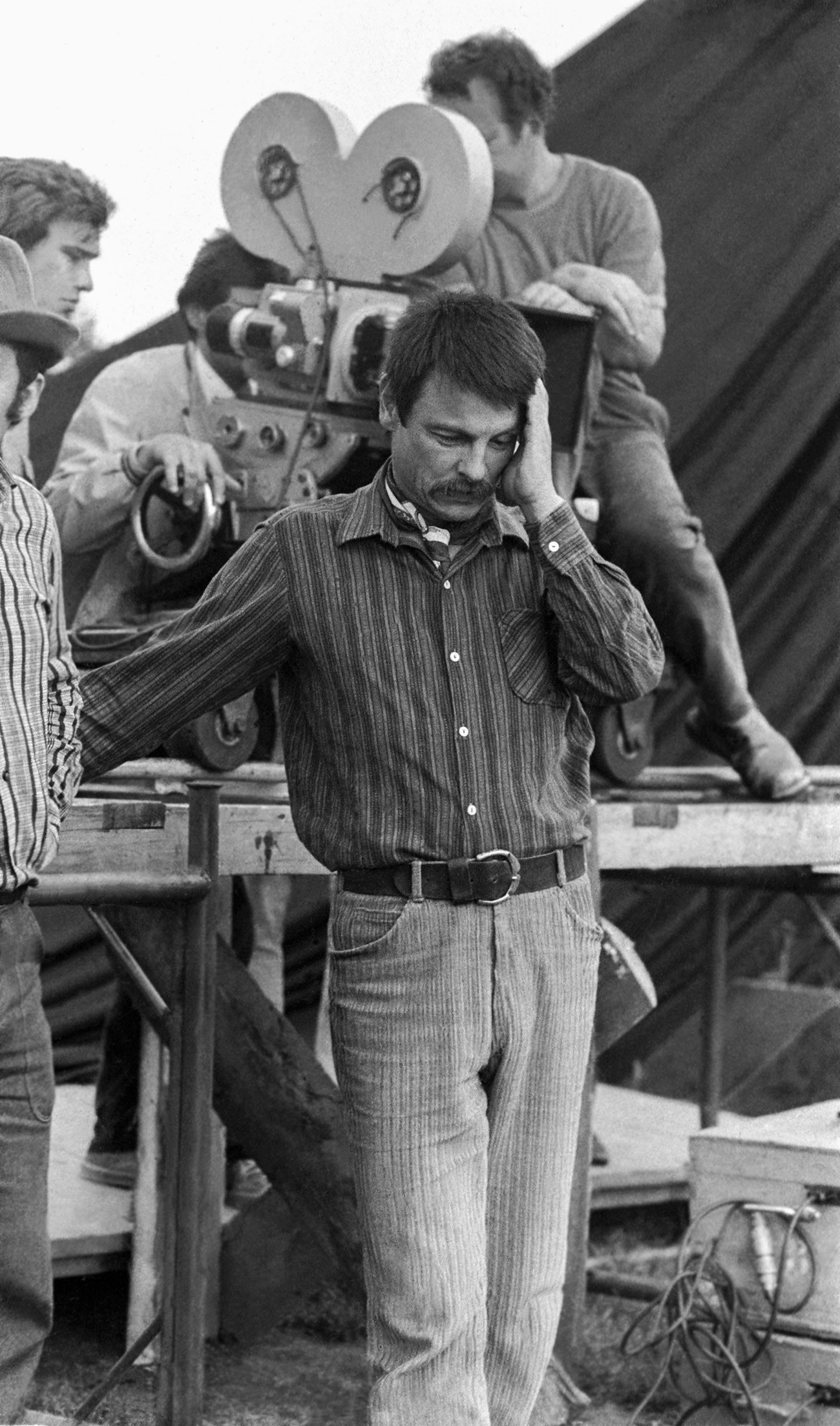

"Tarkovsky is known everywhere. I was amazed when I came to Italy that even a post office clerk, when he saw my name, would exclaim: 'Ah, Tarkovsky! Stalker, Solaris!', says Andrei Tarkovsky Jr., a member of the famous family and the keeper of the director’s archive in Florence.

In a sense, he followed in his father's footsteps: making films, albeit documentary. His latest, called Andrei Tarkovsky. A Cinema Prayer, premiered at the Venice Film Festival this fall.

In an interview with Russia Beyond, Tarkovsky Jr talks about why his father left the USSR, how one should treat art and cinema, and when the director’s museum will open.

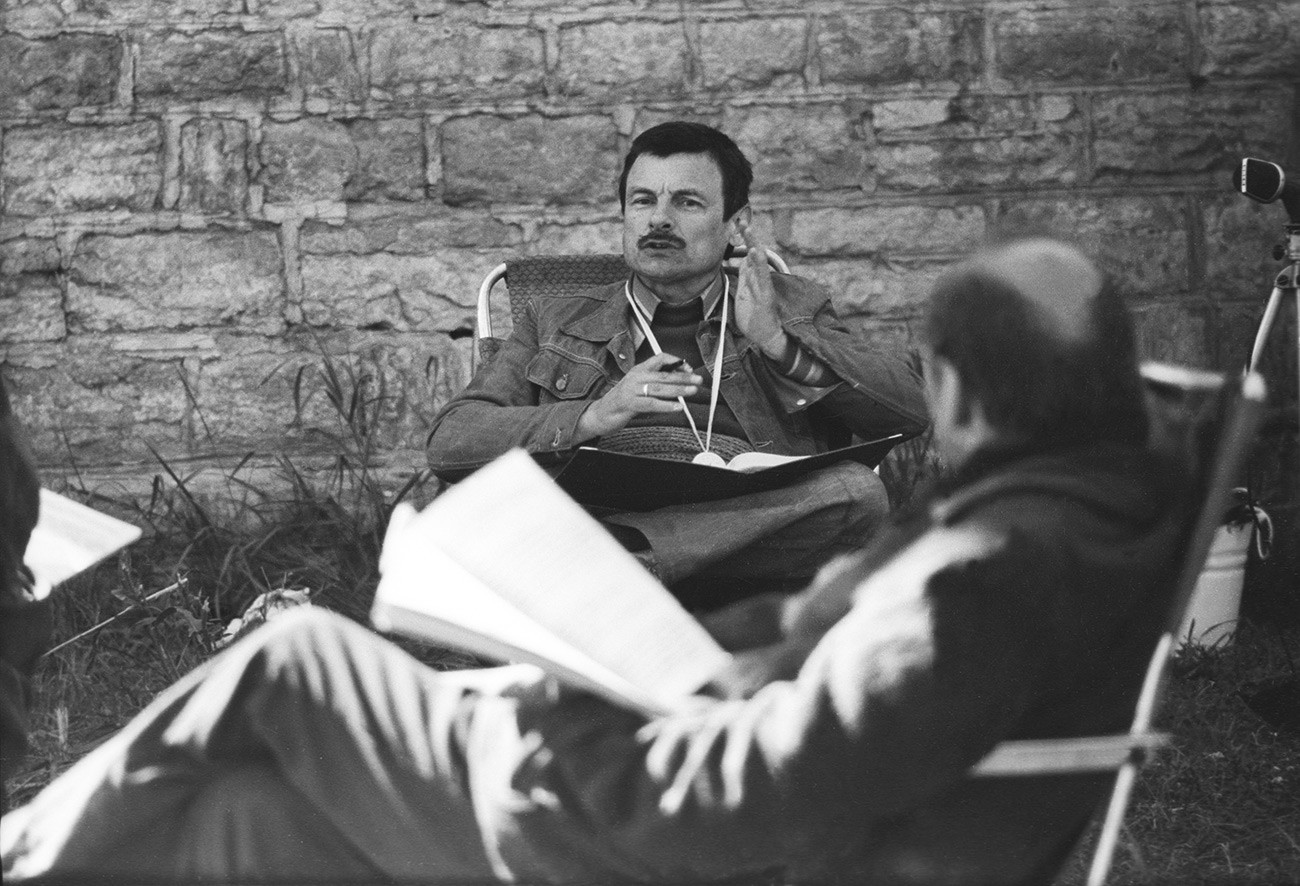

You started making the film about your father in 2003, however, then came a lengthy hiatus. Did the concept of the film change over that time?

Yes, I revised the concept because during that time much had been done and said about Tarkovsky and there was no point in making yet another film about him. The abundance of information resulted in that gradually my father's image began to be lost: his words, his vision, his perception of the world, culture, and art.

When I found his audio recordings in our archive, I realized that the film should not be a film about him, but a film where Tarkovsky tells us about himself. In those recordings, he talks about his life, his view of art, his faith, and about what is important to him. I thought it was an ideal way, here and now, to bring viewers closer to the director, to give them an opportunity to get to know him anew.

In one of the film’s chapters, there is a curious political aspect: Tarkovsky openly says that no small part in his decision to emigrate to Italy was played by severe criticism of his film, Nostalghia, voiced at the Cannes Film Festival by the Oscar-winning Soviet director, Sergei Bondarchuk…

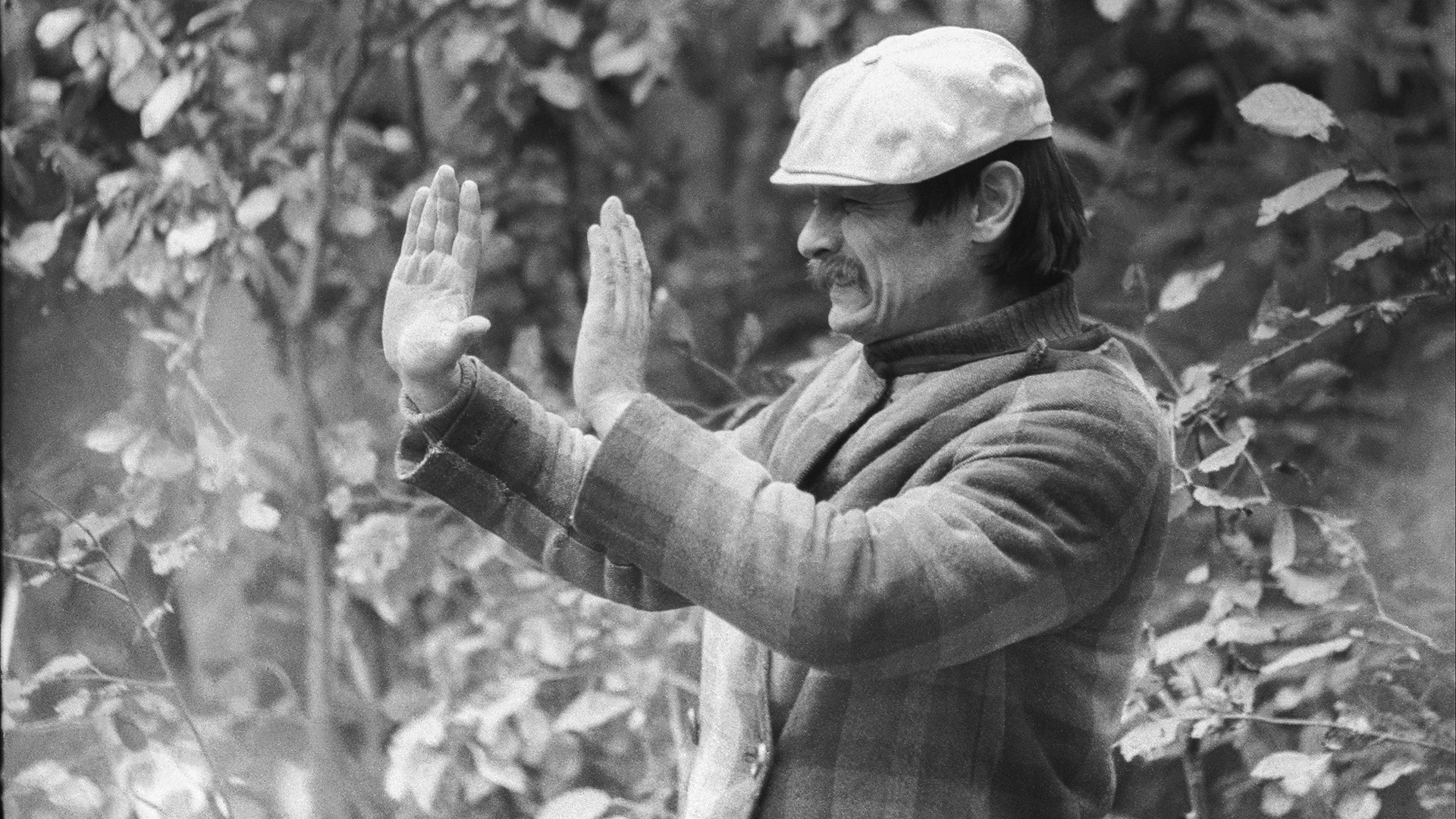

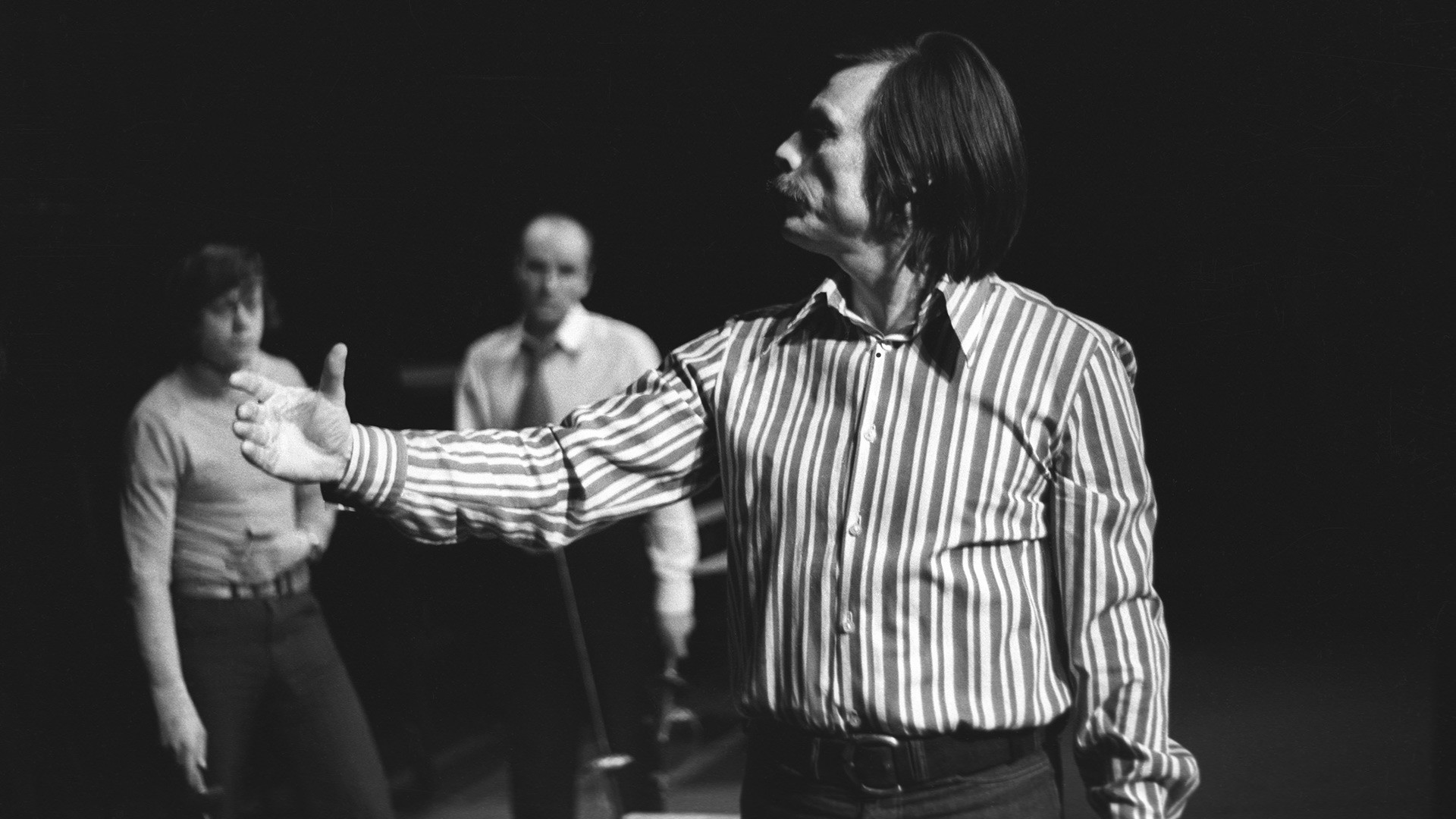

What mattered to me was not the political aspect, but his view of things, of the world, and of what bothered him. Tarkovsky was not a political dissident, he never felt like one and always objected when people told him that he was a dissident. Tarkovsky was not a dissident; he was an artist. The only thing he sought in life and why he left his homeland was the desire to create. He simply had to be able to make films. That was most important for him, and for that he sacrificed everything else.

His first prize, a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Ivan's Childhood, gave him a professional and artistic boost. He was allowed to make his subsequent films, and that helped him further, when he began to be persecuted. People in the West asked: “What is Tarkovsky doing?”, because he was famous, he was known. He had no ambition to receive prizes, this motivation is very common now.

Indeed, in the film he explains why he remained in exile. This is very important because it marked a huge change in his life, it is what influenced his fate. The rest is his inner monologue about art and life. Unfortunately, it is being forgotten. Generally speaking, the attitude to art that he and people of that generation had is no longer in demand. I think it is worth reminding ourselves what we live for and what the meaning of life for people like Tarkovsky was.

Tarkovsky's monologues make it clear how much it mattered to him that his father was a poet. After all, he perceived all art, and his films in particular, as poetry. What was the most important thing that your father gave you?

He was an amazing person to whom I owe my taste in art and in life. He never taught me anything: he believed that children cannot be taught, but they can be shown what is right and what is not, what is beautiful and what is ugly, what is intelligent and what is stupid. He knew how to shape a child's personality without pressurizing or lecturing them.

My father played classical music for me: I listened to Bach with him from the age of three. My first childhood memory of music is The St Matthew Passion. He loved Medieval and Renaissance art and showed me albums, he taught me to appreciate beauty. Maybe at the time, as a child, I did not understand everything, but all those things sink in and return with age.

He always spoke to children as if they were adults, he liked to say: "If you do not understand it now, you will later." When you are a child, you want to understand or to hear that your father is pleased with you. Since then, there's been this desire to stand on tiptoes, to pull oneself up, to jump higher in order to earn father's respect. That too is an education of sorts: no one teaches or lectures you, but they talk to you as an equal, which sets the bar high, and teaches you to be a real man.

Did he guide you in any way in your choice of occupation?

Father saw me working in cinema; he wanted me to work with him on his next film, be a dolly grip or something, he wanted me to train. But I resisted. I studied physics at the University of Florence, as well as history and archeology. Yet, I returned to the world of cinema because all his lessons were not wasted. In 1996, I made my first short documentary film about my father to be shown on Channel One in Russia, and since then I have been working for the Andrei Tarkovsky Institute.

You have spent 25 years working with your father's archive. Are you planning to open a museum?

The institute was founded right after father's death in 1987. In 1995, all the archives and all the materials that Tarkovsky had, were collected here in his house in Florence. This is a huge collection: over 110,000 items of video, audio files, photos, papers, recordings, and scripts. We have a catalogue that is constantly updated because work on the archive is still ongoing.

The archive is under the protection of the Italian Ministry of Culture as a particularly valuable cultural asset. It is located in the house where Tarkovsky lived, and where I live now. The city hall is ready to expand the premises and set up a museum here. The place is very interesting: there is Tarkovsky’s study here, here he edited The Sacrifice (the director's last film, RB), and everything has been preserved.

The municipality of Florence provided the house to Tarkovsky free of charge, and this is how it has remained after his death since it represents a certain value and prestige for the city. We plan to open a museum here by 2022, when my father would have turned 90.

You have lived most of your life in Italy. Do you feel more Russian or Italian?

A Russian person forever remains Russian. I left at the age of 15, which is quite a conscious age, when one already has certain views on life. After that, I returned to Russia for the first time in 1996, and many times subsequently. I had different projects there. If I don't live in Russia, it does not mean that I am not Russian or that I do not want to live there.

Is there a possibility that you may return to your homeland for good?

I divide my time between the two countries and I can return at any time. From time to time I live in Russia, but I have no plans to settle there for good. At least for the time being… But this does not mean that I do not like Russia: you can love your homeland from a distance. You see, the worldview of a Russian person, our spiritual essence, is so particular and strong that it can hardly be changed even if a person lives in another country.

Our perception, goals, search for the truth, the value that we attach to art - this is what the Russian worldview is about. In the West, art is an appendix and material values are far more important, whereas for Russians what matters more are spiritual truths. And art is essential to them, like air.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox