It is 1962. An athletic young woman, her hair pulled back in a tight bun, wearing a modest blouse with a collar and a dark mini skirt, held up by a broad belt and with light-colored shoes on her feet, stands patiently. She is one of 8,000 women in the USSR who applied to go to space. And one of only five who passed to the next stage. Her name is Valentina Tereshkova. She is the daughter of a textile worker and a tractor driver and she’s made it into the first ever female space crew.

Valentina Tereshkova

Valentin Cheredintsev/TASS“We didn’t go wrong with the individual,” her superiors would later say, when Valentina, alone, made 48 trips around the globe and landed in Lake Altai. Khrushchev stood on the tribunes of the Masoleum on Red Square next to Tereshkova and teased the United States: at a time when the bourgeoisie had considered women the weaker sex, socialism was ahead of the curve in terms of equality. Except, it would be another 19 years before another woman got a shot.

There are several versions regarding how the Soviets sent the first woman into space. One posits that Sergey Kovalev, the space program director, was behind the plan - for him, it was the logical step after several missions involving men; another possible reason was that cosmonaut German Titov had visited the States after his ‘Vostok-2’ flight and had heard that the Americans were seriously considering sending a woman up into space.

Whatever the case, Nikita Khruschev got wind of the idea and took to it with much enthusiasm, involving himself in this new chapter of the space race.

The mission was more difficult than the ones involving men: the former were selected from a pool of fighter pilots - and there were no women fighter pilots at the time. So they went for paratroopers. The basic requirements were that they be under the age of 30, with height not exceeding 170 cm and weighing no more than 70 kg.

Holding hands of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (center), Russia's "Romeo and Juliet" space team, Valentina Tereshkova and Lt. Colonel Valery Bykovsky, acknowledge cheers of crowds during welcoming celebrations from atop Lenin's Mausoleum in Red Square here June 22nd 1963

Bettmann /Getty ImagesThe finals saw 30 applicants, of whom only five passed: Zhanna Yerkina, Tatyana Kuznetsova, Valentina Ponomareva, Irina Solovyeva and Valentina Tereshkova - with an aeroclub membership and 90 parachute jumps under her belt.

Twenty-five-year-old Tereshkova “won” the ticket to space - she was chosen as the main pilot. But, behind the scenes, it was established that she wasn’t actually the main candidate. Medical tests and theory placed her dead last (her alternate, Solovyeva, for example, had some 700 parachute jumps behind her, as well as being a Master of sports in parachute jumping. Not Tereshkova).

Nevertheless, Khrushchev thought she was the top candidate, owing to her background: a simple girl from a working family from a Byelorussian village, who, after completing grade seven in school, began working at a tire factory in order to help her mother - followed by a textile factory, together with her mother and sister. Her father died in the war with Finland (1939-1940) and she herself became a Komsomol [Communist Youth Organization] secretary. All of that was true: a real “lady of the people”.

The second determining factor was described by Nikolay Kamanin in his diary - he presided over the female cosmonauts’ training: “Solovyeva or Ponomareva could have been sent the first time around. I’m sure they wouldn’t have done worse - probably even better than Tereshkova, but you could only use them as cosmonauts after the flight… Tereshkova can and must be not only the first woman-cosmonaut. She is smart, she has willpower, she leaves a very good impression with everyone, and would be excellent at speaking on the highest tribunes in the country. Tereshkova must be made into a major public servant. She shall represent the Soviet Union at every international forum with honor and brilliance.”

Tereshkova had her space flight on June 16, 1963. She told her loved ones she was off to a parachute jumping contest. The fact that she flew into space under the call sign ‘The Seagull’ was learned from the news on the radio. The news was good: the Soviet woman spent almost three days in space and felt great. That’s what the official announcements said. In reality, it wasn’t like that.

“Tereshkova, according to the telemetry and monitoring, has completed the flight with adequate results. Communication with Earth-based stations left a little to be desired. She abruptly limited her movement, sitting almost without budging. She showed obvious signs of fluctuations in health and vegetative functioning,” Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky’s report claimed (Yazdovsky was one of the founding fathers of “space medicine”). She did not regularly make logs in the flight journal and did not manage to complete all of the planned experiments.

At one point, Tereshkova even fell asleep from exhaustion at an unplanned time, which she was categorically forbidden from doing. At times, she would not respond to communications from ground control. Only cosmonaut Valery Bykovsky managed to wake her up - his flight had taken place a day before hers, in order for him to be in orbit while Tereshkova was up there (communication was set up between the two - although they could do little but provide each other with moral support; docking was still a technical impossibility at the time).

Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova outside of the Vostok 6 space capsule after landing, june 1963

Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesHowever, the scariest test of strength wasn’t the nausea, grogginess or sleepiness - but something Valentina had kept silent about for 30 years. Her ‘Vostok-6’ ship had the wrong flight coordinates input into the computer. When it was time to correct the orbit and perform the descent back to Earth, the spacecraft instead turned the opposite way, taking Tereshkova into open space. She noticed the issue in time and managed to manually correct the trajectory and set a course back for Earth. But that wasn’t the last of it.

Back on Earth, against all instructions, before the rescue crews had arrived, she treated the locals to some space food in the form of paste, which was intended for research - having a bit of boiled potatoes and kvas herself. Korolev was fuming: “Not one more woman in space, while I’m alive!” he apparently swore.

The story with the space paste could not have played a major role in the decision to never send another woman up into space, as it was quickly forgotten. However, the view that the female organism might not be ideally suited for space flight had begun to take hold. The experiment did not make the space program’s big shots too happy (which was never officially admitted). Though satisfactory, the telemetry was far from ideal and it put a big question mark over the future and practicality of such missions.

“We were preparing another woman for a flight, but Sergey Korolev took the decision not to risk women’s lives, as one of the accepted applicants had already had a family at the time,” Tereshkova revealed. “We were against it,” she continued. “We wrote to the Central Committee, expressing our disagreement with the decision.”

The World Congress for the International Women's Year in Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany, 1975.

SputnikNevertheless, the decision would only be overturned in 1982. Of the remaining four young women cosmonauts, none would see the Earth’s orbit. Valentina Tereshkova remains the only woman in history to have completed a solo flight (later on, women would only travel as part of crews). She was a cosmonaut until 1997, becoming the first woman to be awarded the rank of General of the Russian Army in 1995. She never went back to space, however. But she would get another mission.

“When the issue of what do with Tereshkova was being decided after the flight, I strongly advised Valya to prepare herself for a major social and political role… attempting to convince her that addressing people from elevated state platforms, she would play an invaluable part in in space conquest in our country,” Kamanin recalled.

But Tereshkova insisted that she wanted to finish her education at the military engineering academy, where she enrolled after her flight and continue work at the Cosmonaut Training Center as instructor and test pilot. She had, by then, already married cosmonaut Andrian Nikolayev and given birth to a daughter.

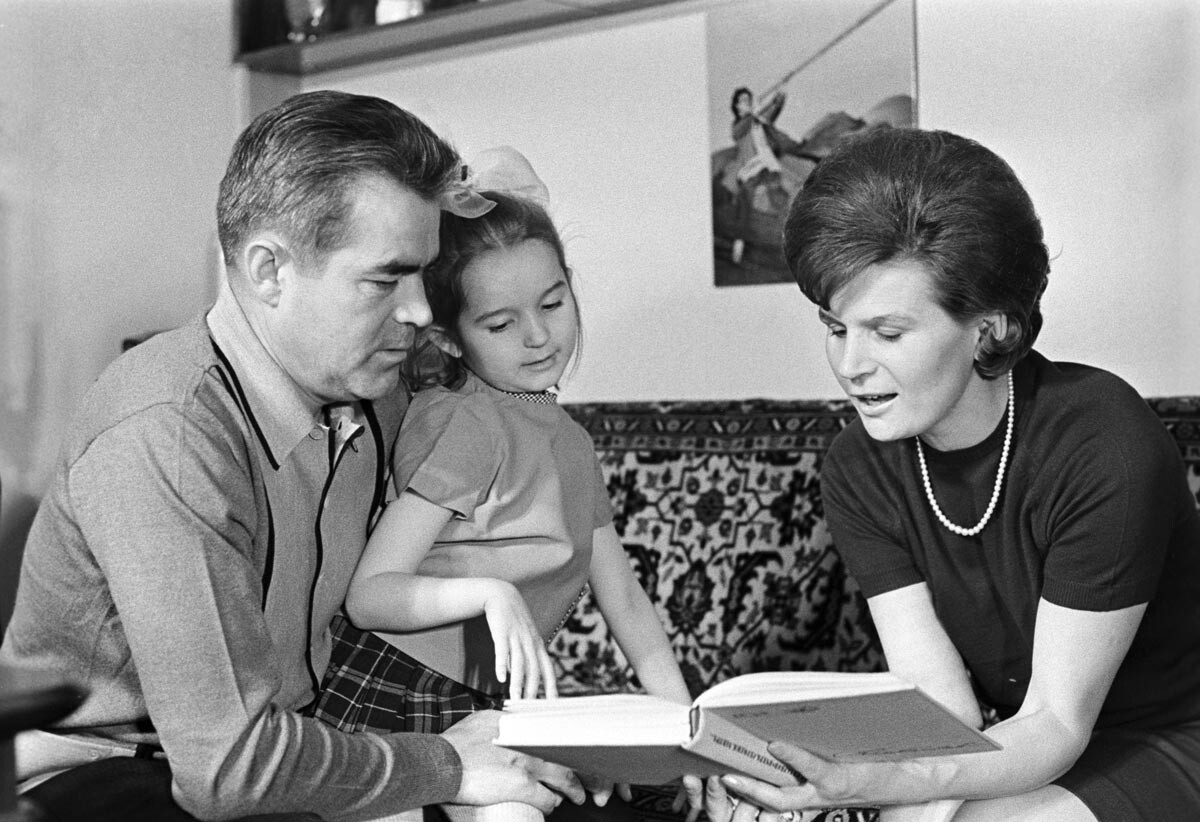

Soviet pilot-cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolaev, his wife Valentina Vladimirovna Nikolaeva-Tereshkova and their daughter Elena.

Vladimir Musaelyan/TASS“She explained her decision with the ailments and health conditions she’d been experiencing for the past two-three years, which have increased, and the desire to take a more active role in raising Alyonka (she is of poor health, often falling sick, and there’s no nanny to speak of), as well as the need to strengthen the family (frequent trips abroad and work in Moscow can negatively impact everyday life). Valya, with tears in her eyes, begged me not to let her go from the Center, that the new job could destroy her,” Kamanin wrote.

But the will of the state proved stronger. Starting in 1966, they would begin forging a politician out of Tereshkova. She became a member of and headed multiple public organizations - the Committee of Soviet Women, the Global Peace Council, the International Democratic Women’s Federation and others - all the way through to being elected as member of the Supreme Council of the USSR and, later, a member of parliament for the Russian Federation.

Tereshkova’s words and authority made her an icon for all Soviet women. “She was a hero. She was a beautiful woman - stately, tall. She loved suits, jackets, blouses with ribbons. She had a great figure. She was elegant and knew how to wear the clothes,” fashion historian Alla Schipakina writes.

Tereshkova’s wardrobe did attract a lot of attention: traveling the world with various committees, she could afford to dress in ways other Soviet women could not. She began receiving letters from them, asking for tips on all manner of things, starting from how to move up the waiting line for an apartment, to how to get their husband to stop drinking. The answers did come, but only as bureaucratic responses in the style of: “Your request has been passed onto the district’s executive committee.”

Tereshkova never gave candid interviews and managed to keep her personal life a well kept secret. She divorced her first husband in 1982, commenting only once on the matter: “In work - he is gold. At home - a despot.” She married again, this time to medical service Major-General July Shaposhnikov.

Since 2015, the former cosmonaut has been involved - as part of her career - in the protection of Christian values. She heads the ‘Memory of the Generations’ charity fund. Tereshkova issued her support for the most resonant state bills, including the increase of the pension age in 2018. In 2020, she proposed the controversial idea of amending the Constitution to allow the removal of restrictions on presidential terms. It was accepted. On March 6, 2022, Valentina Tereshkova turned 85. She is still an acting member of the State Duma.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox