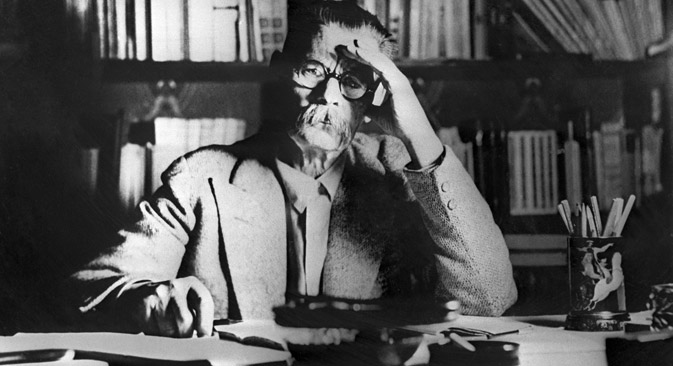

Maxim Gorky in his cabinet in Sorento, Italy, 1931. Source: ITAR-TASS

On June 18, 1936, Moscow Radio announced Maxim Gorky’s death, describing him as a “great Russian writer, brilliant artist of the word, friend of workers and fighter for the victory of Communism.”

The Kremlin honored Gorky with a state funeral, and up to half a million people passed by his coffin in a special chapel in the center of Moscow. After the cremation, the urn containing his ashes was placed on a decorated stretcher and then carried by Stalin and his associates on their shoulders to Red Square – under the watchful eye of policemen and soldiers. Next to Lenin's mausoleum, the politicians gave passionate speeches to the waiting crowd, which numbered more than 100,000.

The French writer André Gide, a personal friend of Gorky, spoke on behalf of the International Association of Writers. Once the ceremony was over, the urn was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, which went directly against the writer’s last wish that he should be put to rest next to his son in Novodevichy Cemetery.

Man of the people

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov took the pen name Maxim Gorky – literally “Maxim Bitter” – early in his youth. Just like Charles Dickens, Gorky represented a whole host of characters from lower social classes in his works, writing about tramps and other marginalized individuals for the first time in Russian literature. Gorky had lived on the bottom rung of society himself and so had firsthand experience of the suffering it brought.

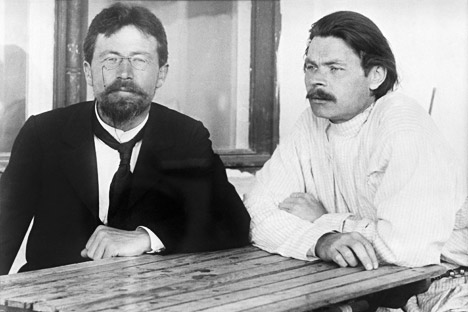

Gorky’s literary fame began before the Revolution, and his writing was highly praised by such greats as Tolstoy and Chekhov. At the beginning of the 20th century, Gorky was already a famous and well-off writer.

Maxim Gorky (right) and Anton Chekhov in Yalta, Black Sea, 1900. Source: ITAR-TASS

He made many trips abroad to countries such as Germany, France, Italy and the United States, where he became friends with many foreign writers, including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, André Malraux and Stefan Zweig.

Gorky had become a close friend of Lenin during the 1900s, so when the Bolsheviks came to power, he was able to advocate for many writers and poets who were being persecuted by the regime for one reason or another.

Lenin eventually grew tired of Gorky’s interventions on behalf of these out-of-favor intellectuals and persuaded Gorky to go abroad to improve his health. After leaving Russia in 1921, Gorky and his family traveled through Europe, before finally settling in the Italian town of Sorrento.

Meanwhile, Lenin passed away in the USSR, and Stalin took over the reigns of government. The new leader was determined to use artistic endeavor as a means of shaping society, and he sought an acclaimed writer to justify his policies. He chose Gorky.

In 1932, the writer returned to the USSR, where he received many honors. He was elected president of the newly created Soviet Writers’ Union, and his birthplace, Nizhny Novgorod, was renamed Gorky.

Mounting tensions

As the 1930s drew on, Gorky’s position within Soviet society became more conflicted. He led the propaganda campaign for the White Sea Canal, which was built with heavy loss of life by prisoners of the Gulag. In his book “The Gulag Archipelago,” Alexander Solzhenitsyn characterizes Gorky’s actions during this period as “material self-interest” rather than delusion.

The first congress of the Union of Soviet Writers was scheduled for the summer of 1934, and Gorky was asked to give the opening speech. However, in May of that year the writer’s son, Maxim Peshkov, died days after returning from a binge with Genrikh Yagoda, the Soviet Interior Minister.

There was speculation that Maxim had been killed to frighten Gorky and prevent him from making unwanted comments or inflammatory speeches during the congress. Whatever the truth, Gorky was devastated, and the congress had to be postponed until August. The writer did ultimately appear, giving a seminal speech on the future of Soviet literature.

The strain between Gorky and Stalin continued to grow, until relations broke down completely in June 1935. Gorky pulled out of the First International Congress of Writers in Paris at the last minute, citing health problems.

Although Gorky really was very ill with tuberculosis, Stalin took it as an unpardonable betrayal, particularly as Russia had organized the event itself. Gorky was forbidden from communicating with foreign writers and was placed under constant surveillance, hardly leaving his luxury mansion in the center of Moscow.

Rumor has it that in Gorky’s last years Stalin asked him to write his biography, but the writer firmly refused. The Russian historian Arkady Vaksberg claims that Gorky did not die from heart disease as the official version states but was poisoned on Stalin’s orders. However, this is unproven, and in any case the writer was a very sick man by this late stage in his life.

When the Maxim Gorky finally died, his brain was surgically removed within a couple of hours. It is still held in the Neurological Institute in Moscow, along with the brains of Mayakovsky, Lenin, and many other Russian thinkers, writers and politicians.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox