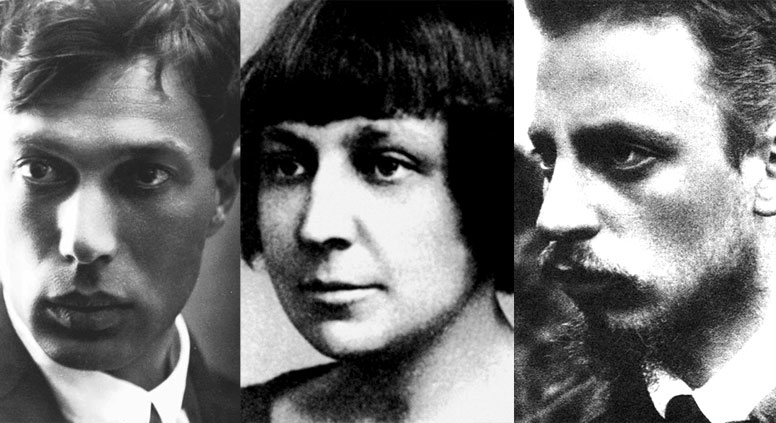

L-R: Pasternak, Tsvetaeva, Rilke

During the early years of World War I and the following Bolshevik Revolution, Boris Pasternak and Marina Tsvetaeva both lived in Moscow, moving in the same literary circles without catching each other’s attention.

A love affair in letters

Tsvetaeva left Russia in 1922 to live in Prague with her exiled husband, Sergei Efron, who had escaped the revolution several years earlier. Later that year, Pasternak read her poetry collection “Versts” and immediately wrote her a letter expressing his deep admiration for her work. This was the spark for an intense romantic relationship expressed through letters brimming with poetry, love, doubt and jealousy.

The two young poets quickly discovered how much they had in common. Aside from their similar ages and upbringing in Moscow, they both had a professor father and a pianist mother. They had also both visited Germany on several occasions and shared a love of German literature.

In spring 1926 Boris Pasternak was going through a period of deep artistic dissatisfaction and even considered abandoning literature. It was thanks to Tsvetaeva’s support and understanding that he was able to finish his major poem “The Year 1905.” Then two important events occurred – on the same day – that filled him with a new hope and energy. The first was reading Tsvetaeva’s “Poem of the End,” in which he recognized himself. In response he wrote, “You are mine and have always been mine; all my life is – you.” The second event was a letter he received from his father with the news that Rilke had read some of his poems in a Paris journal, which stunned and delighted him.

Spiritual triangle

Rainer Maria Rilke’s name had appeared repeatedly in the letters that Pasternak and Tsvetaeva exchanged from 1922-1925, and in the late spring of 1926 the Bohemian-Austrian poet added his voice to their correspondence.

Rilke sent Pasternak his “Sonnets to Orpheus” and “Duino Elegies,” and in his warm letter of thanks, Pasternak mentioned Tsvetaeva, speaking of her as a major poet with a great love of Rilke’s work. At Pasternak’s request, Rilke sent Tsvetaeva copies of his new books; she responded with the words, “You are the very incarnation of poetry.”

Rilke was dying of leukemia in a health spa in Val-Mont, Switzerland, so the correspondence between the three poets was brief but intense. Each poet was facing their own form of desolation – exile, imminent death, alienation – and their letters to each other were a way of escaping their solitude and retreating into the comforting world of lyricism and passion.

No happy ending

Tsvetaeva and Pasternak were eager to visit Rilke in Switzerland, but the meeting did not take place before Rilke died on Dec. 29, 1926. Tsvetaeva and Pasternak continued writing to each other for another nine years, but their letters declined in intensity and their romance faded – particularly after she learned that he had left his wife for another woman.

The two poets did finally meet in 1935, when Stalin forced Pasternak to attend the Soviet-inspired “International Writers Congress in Defense of Culture” in Paris. Pasternak was on the verge of a nervous breakdown when he arrived for the event and his meeting with Tsvetaeva was a damp squib. Despite their extraordinary literary intimacy over so many years, they were unable to find a common language. When Tsvetaeva asked about the possibility of returning to Russia, Pasternak replied, “You’ll get to love the collective farms” – a comment laden with sarcasm that went over her head.

In a letter to fellow poet Anna Teskova, Tsvetaeva said, “It happened – and what a non-meeting it turned out to be!” She also accused Pasternak of “weakness or cowardice” in not refusing to attend the conference. Their literary and emotional relationship had clearly reached its end.

The pair did meet again, but it was under sad circumstances: Pasternak did his very best to help when the NKVD arrested Tsvetaeva’s husband and daughter for “espionage” after she returned to Russia.

There was to be no fairytale ending for the relationship that the writer Joseph Brodsky called one of Russian literature’s greatest and most breathless love stories.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox