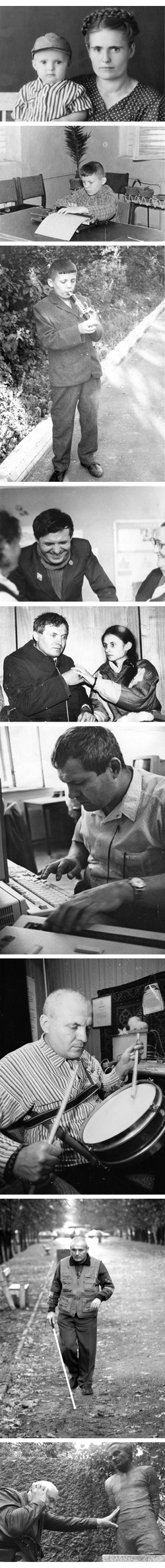

Professor Alexander Suvorov, Russia’s only deaf-blind doctor of psychology and a truly unique individual, marks his birthday by remembering his teachers, students and other empathetic people he has met in his life.

He was born in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (back then, the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic) on June 3, 1953, in a family of policeman Vasily Suvorov and local railway worker Maria Suvorova. At the age of 3 he suffered a sudden loss of vision, and at 9 he developed hearing problems. However, he only fully comprehended his deaf-blindness later at the age of 16, when recovery proved impossible. The reasons behind the disease remain unknown.

From denial to acceptance

“That morning [on learning there was no cure] I ran out of the bathroom to the playground and cried three hours. It was the moment of realization: deaf-blindness is my everlasting nightmare - something that makes me inferior, that separates me from the world and all its culture, enormity, and beauty. I missed music most of all. Later I cursed my disease for other reasons, above all the inability to see, hear and admire loved ones."

Probably these thoughts wouldn't have hit him so hard if he hadn’t been so sensitive and well educated, if he'd been brought up like many other disabled children in forced isolation from society who simply do not understand how to communicate. But he was (relatively) lucky.

In 1964 his mother brought 10-year-old Alexander from remote Bishkek to the newly-opened Zagorsky orphanage for deaf-blind children outside Moscow, founded by the prominent Soviet scientists and pedagogues Ivan Sokolyansky and Alexander Mescheryakov, philosopher Evald Ilyenkov, and other professionals. It was one of the first institutions in the world where deaf-blind children could get high-level education and training, allowing them to live full lives, work, and take care of themselves.

The core point of Mescheryakov's pedagogical system is “jointly divided activity.” At first, the teacher stands behind the child and directs the movements of his or her arms, gradually applying less force until the child starts doing it independently. Step by step they progress from primitive actions to more complex and conscious tasks.

In 1971 Suvorov was chosen to be part of the test group for the so-called “Zagorsky experiment".

From acceptance to action

Under the Zagorsky experiment, Suvorov and three of his deaf-blind fellows from the orphanage were prepped to enter Moscow State University (MSU). In 1971 he started to study at the Faculty of Philosophy, later moving to Psychology. The experiment was conducted with the help of different state institutions, and every deaf-blind student was accompanied by a personal assistant.

After graduation he was employed at the Academy of Pedagogical Science of the USSR as a junior researcher. In the 1980s he started to practice his pedagogical skills and ideas at the Zagorsky orphanage.

The secret of the system lies in its individual approach. It seems so simple and obvious even when talking about ordinary healthy children. With deaf-blind kids, there can be no fixed program. The defect level varies from child to child. Total deaf-blindness is a rare diagnosis, and usually it's a combination of blindness and weak hearing, or vice versa. However, often it is accompanied by neurological, mental, or locomotor disorders. Therefore, it's hard to train such people for the workplace, even menial jobs.

Today, some work as massage therapists (thanks to their unique ability to feel things by touch), or as teachers for children with the same disabilities. Some even take part in theater performances. Last year, for instance, the show "The Touchable," staged by Moscow’s Theater of Nations, caused a stir. Among the professional actors were deaf-blind people. Alexander Suvorov was one of them.

In 1991 Susquahanna University (Pennsylvania, USA) honored Suvorov with the title of International Doctor of Humanities. But for him the most precious title is “children’s coat-peg,” given because children adore him and hang round him.

From action to reflexion

"After the Zagorsky experiment two other girls graduated from MSU, who now work at the orphanage. In the early 90s the system collapsed. It seemed preferable to keep disabled teens at the orphanage as long as possible – at least, there they could do something. There were workshops and they were safe. The futureless alternative was to become a mere vegetable in a psycho-neurologic ward or at home, where your relatives didn't have the skills to empower you," says Suvorov in the interview.

Now 63, he has penned more than 20 books, both scientific and literary (he has written poems since adolescence), takes part in creative and pedagogical activities, and supports disabled children and their parents. Last year he became president of the Community of Families with Deaf-Blind People, initiated by the “So-edinenie” Deaf-Blind Support Foundation. He talks to parents and tells them not to give up hope. Because even the Zagorsky orphanage is not all-powerful — life separated from family is, in fact, a social orphanage. He describes solitude as the “most disastrous consequence of deaf-blindness.”

His life lesson teaches us not to step back into the darkness, not to shy away from offering (and taking) a helping hand to another person. This rule applies equally to us, the sighted and hearing.

Photo credit: www.suvorov.reability.ru, Tatiana Gurova

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.