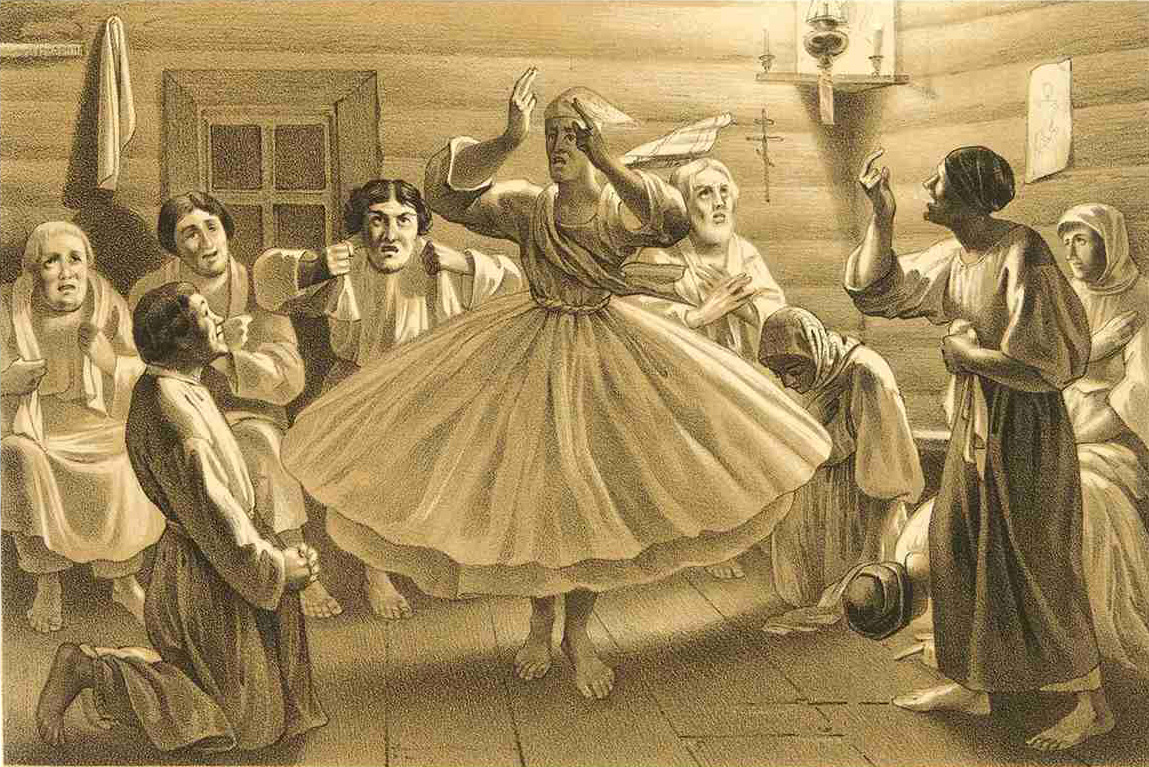

The radenie ritual.

Provided by Oleg Skripnik"I am not the father of sin: Accept my act and I will recognize you as my son." According to legend, this is what founder of the mystical Skoptsy sect, the peasant Kondraty Selivanov, said to Russian Tsar Paul I. The emperor was not impressed by Selivanov's teachings and sent him to a monastery for madmen. However, by this time the idea promote by the Skoptsy that castration is salvation from sin had already spread through Russia and Selivanov had acquired many followers.

The word skoptsy derives from the outdated term oskopit, meaning “to castrate.” The sect members did not call themselves by this name, preferring romantic epithets such as God's Lambs or White Doves. In their heyday the "dove" communities flourished both among the illiterate provincial peasantry and in the merchant houses of St. Petersburg.

Ritual self-castration was observed among ardent Christians long before the appearance of the sect. The most important tenet of the Skoptic faith, which inspired ancient Christian theologian and ascetic Origen to castrate himself, came from a passage in the Gospel According to Matthew: "There are castrates who were castrated by others and there are castrates who castrated themselves for the Kingdom of God."

Radenie. Source: Wikipedia.org

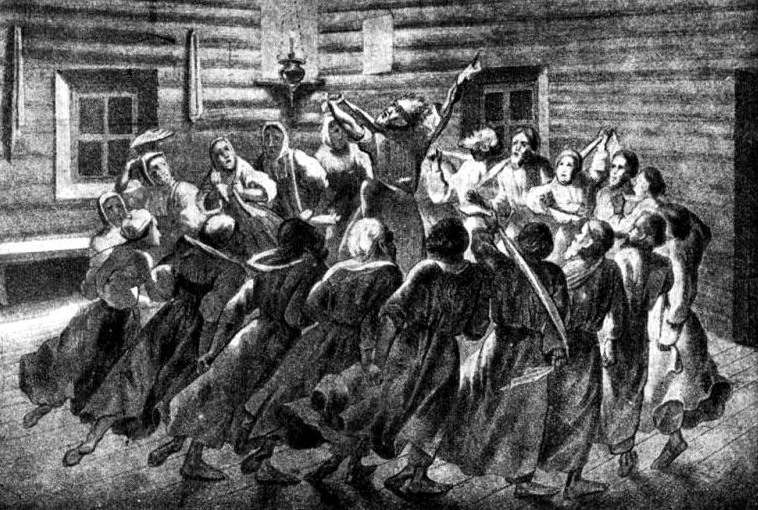

Radenie. Source: Wikipedia.org

Later, the sectarians started interpreting even innocent excerpts from the Bible in their favor: for example, that Christ, after having washed his apostles' feet, also castrated them.

It can be said that the Skoptsy was a small doll in the great matryoshka of Russian sectarianism. It split from another sect, the Khlysty (a people's sect with strict asceticism and ecstatic-dance worship), which in turn became an Old Believer sect (Old Believers are essentially no different from Orthodox believers but in the 17th century they did not accept church reforms and separated from the official Orthodox Church). The Skoptsy preserved the views of the Khlysty but went even farther. They practiced "fiery baptism" – castration for men and the cutting off of breasts for women.

Historian and sect scholar Sergei Tsoya believes that the reason for such active formation of sects at the time was that all too many people began perceiving the official Orthodox Church as an overly bureaucratic and degraded structure. This led those who were disillusioned to search for true faith in sects.

The sect's fathers are considered to have been three peasant Khlysty from the Orlov Region (220 miles south of Moscow), who castrated themselves and 30 other people. They believed that by saving themselves from the sin of lust they would live eternally. One of the castrated men was Kontrady Selivanov, who soon proclaimed himself to be Christ.

In 1772 the sectarians were sent to Siberia but this only benefitted the self-proclaimed martyr. Twenty years later Selivanov returned to St. Petersburg as an authoritative mystic, having converted dozens of people to his faith.

In the 1790s the Skoptsy began to appear among merchants and soldiers. In 1802 the sect accepted its first aristocrat, Alexei Yelensky, who had absorbed the spirit of the sect during exile. In 1804 he even sent the emperor a proposal to deliver Russia to the power of the Skoptsy, which resulted in his second exile.

Selivanov did not meddle in politics but with his radeniya worshipping became popular among the capital's bohemian crowd – back then mysticism was in vogue. An official by the name of Lubyanovsky used to say that Tsar Alexander I visited Selivanov before the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805. The Skoptsy leader begged the emperor not to "wage war with the cursed Frenchman" and predicted Russia's defeat.

The sect's legal life came to an end in 1817 when a pair of White Guard officers were castrated. Selivanov was arrested, but it was too late – the sect had spread among the cities.

By the second half of the 19th century the Skoptsy were a common phenomenon in Russia. "The skopets who holds the shop generally lodges upstairs," wrote Dostoyevsky of a typical money-lending premises in a tenement house in his novel The Idiot. The sect attracted various social classes. For the merchants and aristocrats this was a fad, a mystic exoticism.

The introduction of Skoptic motifs in folklore and the general "folk character" of the sect won over the peasants, many of whom were persuaded to castrate themselves by the Skoptsy promises of eternal life and of sex as sin. The sect had accumulated a lot of wealth and used it to proselytize people: It bought peasants, provided shelter for orphans, supported the unfortunate. Information about the number of members varies: Some say 6,000, some say hundreds of thousands, some even go up to a million.

"Before the revolution the government did not fight the sects effectively, it often closed its eyes," says historian Sergei Tsoya. "Also, in the 19th century the government did not have strong control over the big territories. The oppressed just took their communities to Siberia or the north." The bloody sect was finally destroyed only during Stalin's reign – with repressions and arrests.

Today the Skoptsy sect is believed to be no more. Some dubious sources say there are 400 Skoptsy alive today, but there is no serious proof of this. Modern followers of the Skoptsy can in a certain way be called “anti-sexuals.” "In Russia there are about 2,000 anti-sexuals and among them are religious ascetics," says Mirra, an activist from the movement. "And a section of them welcomes self-castration."

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox