A glass of wine and grapes at Massandra winery in Crimea

Vladimir Astapkovich/RIA NovostiIn the 17th century the monarchs of the newly established Romanov dynasty turned their eyes to wine production. Until then, the country didn't grow grapes to produce wine, and for centuries it had to be imported from abroad.

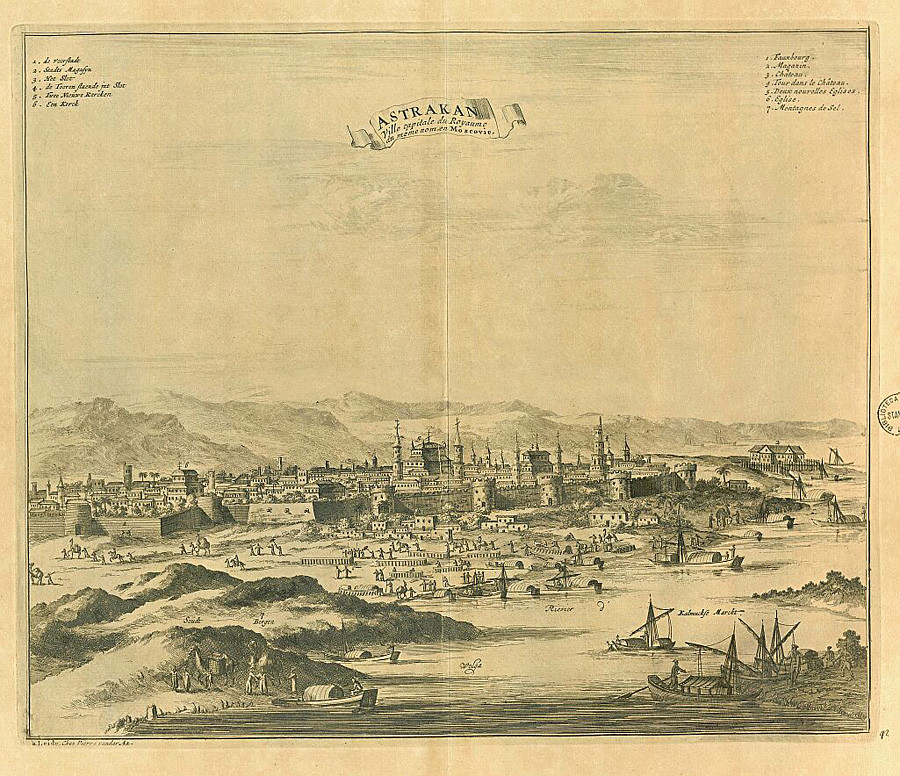

Immediately after ascending the throne in 1613, Mikhail, the first Romanov ruler, ordered to create “a garden of the tsar’s court.” The “garden” in fact was the first grape plantation in Russia, located at a monastery in the city of Astrakhan on the Volga River delta, about 1,500 kilometers south of Moscow.

The city of Astrakhan at the end of the 17th century

Public DomainLater, an expert gardener from one of the German principalities was invited to modernize grapevine cultivation in Russia, and by the mid-1650s Mikhail’s successor, Tsar Alexei, was already drinking the first Russian wine made in Astrakhan. At about this time, grapevines began to be cultivated on the Don River, also in the south.

Wine production in Russia was boosted by new conquests. Under the rule of Peter the Great in the early 18th century the southern lands along the Azov Sea coast were pacified, and the Tsar pushed Russia's borders deeper into the Caucasus region. All these places were favorable for growing grapes.

An assemblée under Peter I by Stanisław Chlebowski, 1858

The State Russian MuseumThe most prominent region for winemaking, still famous today, was taken by Russia later that century. In the 1780s, Catherine the Great defeated the Turks and secured control over Crimea and the lands that she called Novorossiya (“New Russia,” which comprised contemporary Krasnodar Region and a large part of modern eastern Ukraine).

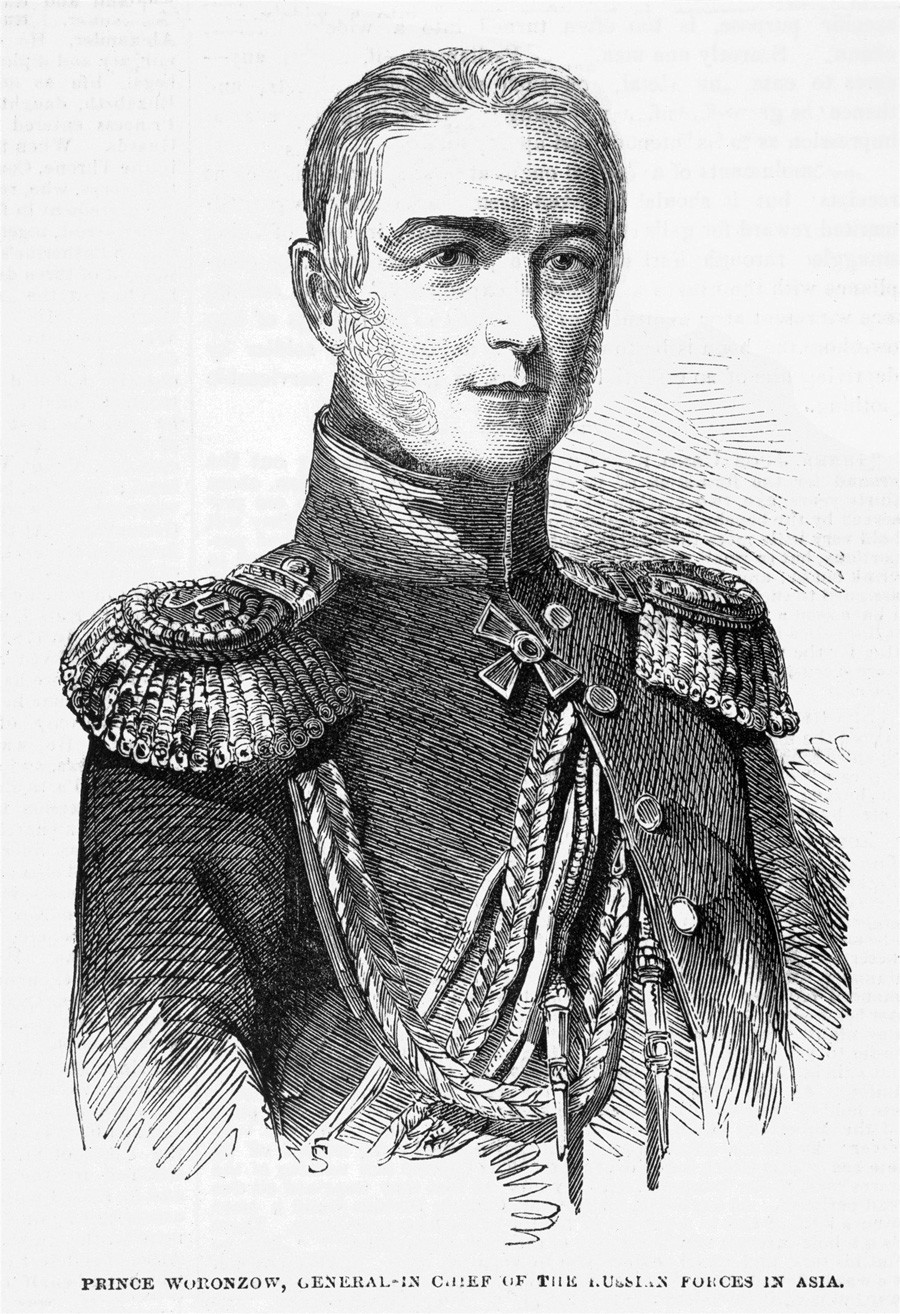

The development of the wine industry in these new regions of the Russian empire is mainly connected with two men. The first is Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, governor of Novorossiya for more than three decades (1822-1854). In his Crimean estates he grew various sorts of grapes, and built special cellars for wine storage.

Mikhail Vorontsov

Mary Evans Picture Library/Global Look PressVorontsov supervised the appearance of the first Crimean school of winemaking, whose staff were the first specialists to fortify dessert wines with rectified spirit, thus speeding up the process of wine maturation and improving its qualities.

In the late 19th century, the Imperial family bought some of Vorontsov’s estates from his heirs, and another Prince, Lev Galitsyn, became the new official in charge of winemaking innovation on Romanov lands. He proposed building a huge wine cellar where wine from different estates belonging to the Romanovs could mature.

With the help of a geologist he found a place on Crimea’s southern shore with a constant temperature of 12-14 degrees Celsius. Galitsyn built a gigantic cellar with seven long-stretched tunnels able to hold 250,000 deciliters of wine in barrels, as well as a million bottles. The cellar has since been a part of the famous Massandra winery.

The Golitsyn cellars at the Novy Svet winery in Crimea

Artem Kreminsky/RIA NovostiGalitsyn is often called the founding father of commercial winemaking in Russia. Besides the Massandra winery, he set up the first professional production of sparkling wines in the small town of Novyi Svet, his own estate in Crimea. Galitsyn also did much to develop vineyards in Abrau-Durso, near the port of Novorossiysk on the Black Sea.

Statues of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (L) and wine maker, prince Lev Golitsyn, at the Novy Svet winery in Crimea

Alexei Pavlishak/TASSGalitsyn said that his goal was to foster a culture whereby “ordinary folks would drink good wine, not poison themselves with hogwash.” That would take time, however. The mass production of quality wine picked up steam under the Soviet regime but only in the 1930s in the time of Stalin.

When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917 they decided to continue the Imperial government's 1914 wartime ban on the production and consumption of all alcoholic beverages, which lasted until 1923. Then the approach to alcohol was radically changed. Later on, the authorities put a special stress on wine.

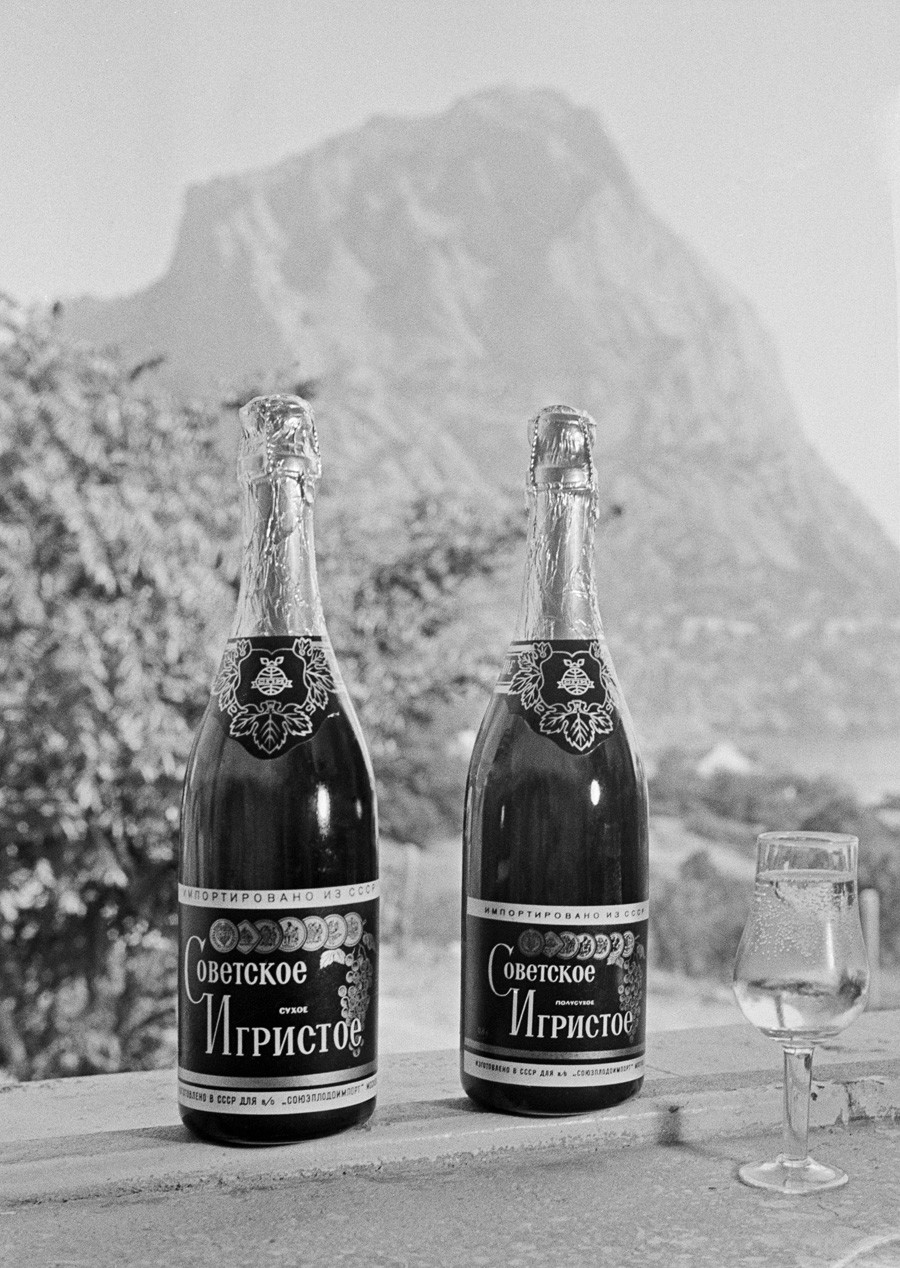

Sparkling wines made at the Novy Svet Winery

Valentin Kunov/TASSIn 1936, the Soviet government implemented a policy to boost the production of sparkling, dessert and table wines, as well as brand wines. As Anastas Mikoyan, one of the highest-ranking Soviet officials of that time put it, “champagne is a sign of material well-being and prosperity.”

Soviet sparkling wine was made to resemble champagne (called shampanskoe in Russian), which has associations of the upper class. The Soviet government wanted to make a statement, that the favorite drink of the European aristocracy was affordable to common Soviet people.

Cheap, quick to produce, and of reasonable quality, the Soviets believed that they had accomplished the task. In 1937, the official production of Sovetskoe shampanskoye began, and was made using an advanced, newly developed technology.

Anton Frolov-Bagreev, who started his career at the Abrau-Durso estate under Golitsyn, was the brains behind the new method. Sovetskoe shampanskoye quickly became popular, and in the 1950s the technology was further developed. Later, a license for the Soviet method of sparkling wine production was even bought by Moet and Chandon.

A student party in the Soviet Union

Evgeny Tikhanov/RIA NovostiBrand wines were also loved in the USSR, and its production increased dramatically in the late 1930s. Brand dessert wines such as “Ulybka” (Smile) and “Chernye glaza” (Black eyes) were produced for decades and earned the adoration of consumers.

The development of the Russian wine industry was set back tremendously in the second half of the 1980s, however. During Gorbachev’s prohibition campaign whole vineyards were destroyed, and the industry was dealt a heavy blow. It somewhat recovered when he was removed from power, and by 2014 Russia ranked 11th globally for the amount of land under cultivation in wine production.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox