If you visit a Russian friend’s home for a holiday meal or party, don't be surprised when you’re met with an abundance of fatty dishes. Most likely, there will be several types of salad (always including potatoes and beans) and oven-baked pork with cheese, not to mention some fried pirozhki (small pastries) with cabbage. And all these dishes will contain a lot – really a lot, we’re not exaggerating here – of mayonnaise. What about ketchup, you might ask? Or a nice cheese sauce? Nope. No, other sauce is held in such esteem among Russians as mayonnaise. So what’s its secret?

Carousel hypermarket in the Moscow Region.

Maksim Blinov/SputnikWhile sour cream is the main sauce of traditional countryside cooking in Russia, mayonnaise is the real legend in Soviet cuisine. And it is not just a salad dressing – it is also the most important ingredient in main courses, baked foods

The Russian internet is full of jokes about mayonnaise's ability to enhance pretty much any dish

"When you slice some sausage into instant noodles and dress with mayo. Cooking level: God."

Pikabu.ru

Instant noodles? Instant noodles with mayo!

Pikabu.ru

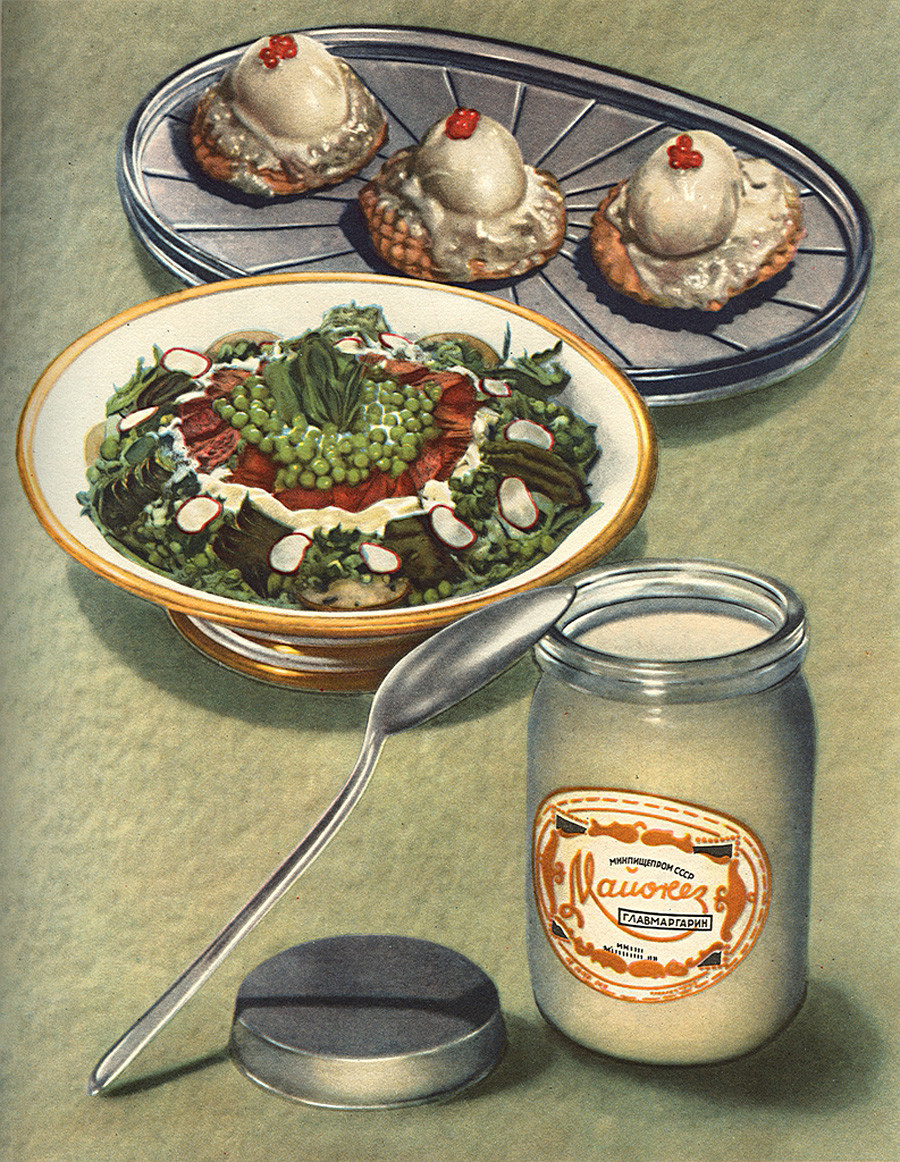

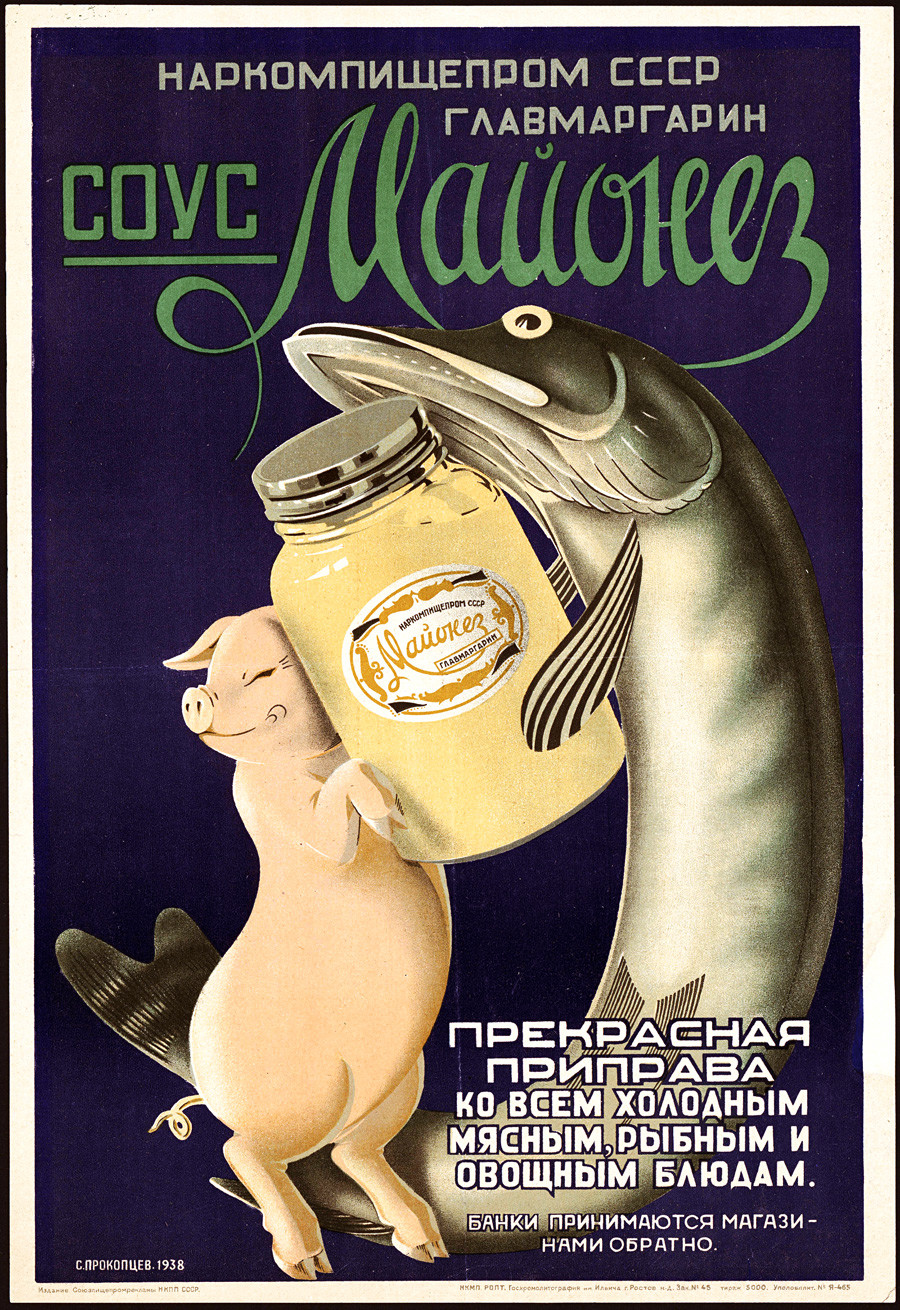

Nowadays, many nutritionists consider mayonnaise a rather unhealthy food, but in the

Joseph Stalin personally approved the first batch, after which mayonnaise went into mass production.

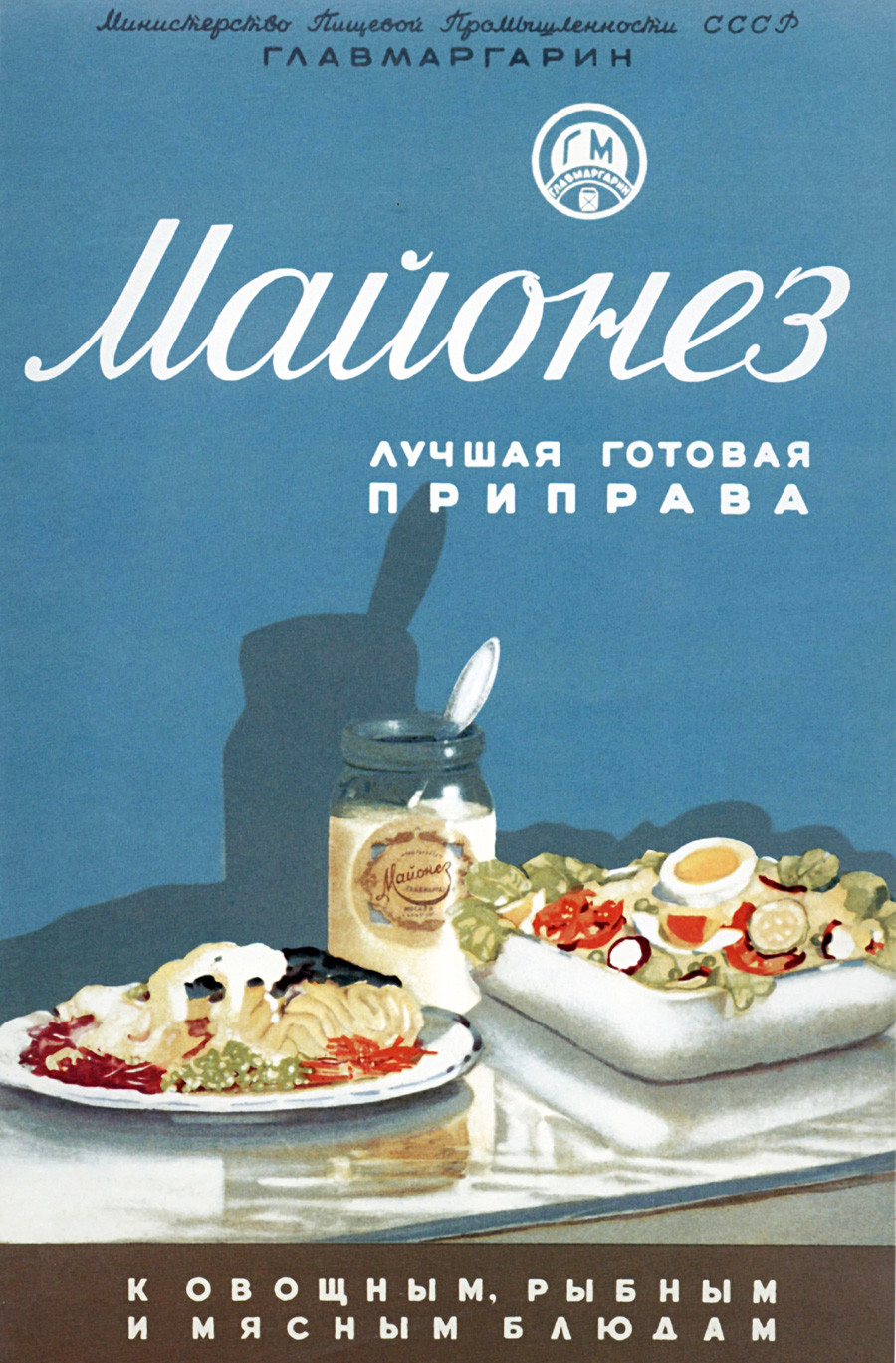

As a matter of fact, mayonnaise is a long-established French sauce that goes back to the mid 18th century.

And while, yes, mayonnaise probably would not have been suitable for anyone on a diet, it was perfect for factory workers because it was fatty, tasty and filling. And so many dishes could be made with it!

When the first edition of the Book of Tasty and Healthy Food was published in 1939 (also written under Mikoyan's personal supervision), mayonnaise was already described as an ideal condiment for everything under the sun. Subsequently, the book was reprinted numerous times in large print runs, reaching just about every Soviet household.

In addition to mayonnaise, Mikoyan also brought ketchup from America. There is evidence to this effect in the first edition of the Book of Tasty and Healthy Food, which also notes that every American housewife had the sauce in her kitchen.

During the Cold War, as relations with the U.S. went downhill, Soviet food products stopped flaunting their "American roots." All references to links with the U.S. disappeared from the main cookbook, and people had to forget about ketchup altogether until the 1980s when the USSR started importing it from Bulgaria. Meanwhile, the foreign origins of mayonnaise were suppressed, allowing its status in Soviet cuisine to remain unchanged. Perhaps this is why it remains much more popular than ketchup or any other foreign condiments to this day.

When we speak of Russian cuisine, we are often actually speaking about Soviet cuisine. Before the revolution, Russia lacked a single coherent national cuisine. Different regions ate differently, but, as a rule, standard fare consisted of cooked grains and soups made with whatever grew on people’s vegetable plots, along with pheasants and the like served at high-society gatherings. Soviet cuisine gave regional cuisines a common denominator, and the whole country began eating identical dishes prepared with more or less the same ingredients following recipes drawn from a single cookbook. This is why many of Russians’ favorite dishes are Soviet foods they remember from childhood.

And mayonnaise was the foundation of the three pillars of Soviet cuisine: Oliviersalad, Mimosa salad and “herring under a fur coat.” Without it, it is difficult to imagine “French-style meat” (a dish of pork with cheese and mayonnaise that is actually unknown to the French, shortbread cookies or, for that matter, pelmeni.

In the Soviet years, people had to conjure up a first, second and third course (as well as a fruit drink) out of readily available and simple ingredients like potatoes and tinned fish. Mayonnaise was a perfect aid in achieving this objective: It makes dough lighter, meat more tender and salads zippier. It’s no wonder then that hunting down mayonnaise was a real challenge, particularly in years when there were food shortages (1970s-1990s). “Don’t touch! It’s for New Year!” When this cry rang out, you knew it was about mayonnaise.

After the collapse of the USSR, a wave of new foreign products, including dozens of new types of table sauces and condiments, swept over the Russian market. But wins out over nostalgia in the end? Many Russians buy mayonnaise for old time’s sake and to be reminded of the taste of salad JUST the way their mom used to make it. It is said that if you don’t make Olivier salad, the New Year won’t come. And no Russian yet has dared find out if it’s true.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox